| disease | Angina Pectoris |

| alias | Angina Pectoris |

Angina pectoris is a clinical syndrome caused by insufficient coronary blood supply, resulting in acute, temporary myocardial ischemia and hypoxia. It is characterized by paroxysmal, oppressive pain in the anterior chest, which may be accompanied by other symptoms. The pain is primarily located behind the sternum and can radiate to the precordial area and left upper limb. It often occurs during physical exertion or emotional stress, lasts for a few minutes, and subsides with rest or the use of nitrate preparations. This condition is more common in men, with most patients being over 40 years old. Common triggers include fatigue, emotional agitation, overeating, exposure to cold, rainy weather, and acute circulatory failure.

bubble_chart Pathogenesis

Mechanical stimulation of the heart does not cause pain, but myocardial ischemia and hypoxia do. When there is a discrepancy between the blood supply of the coronary {|###|} artery and the myocardial demand, and the coronary {|###|} blood flow cannot meet the metabolic needs of the myocardium, causing acute, temporary ischemia and hypoxia, angina occurs.

The amount of myocardial oxygen consumption is determined by myocardial tension, myocardial contractility, and heart rate. Therefore, the "heart rate × systolic blood pressure" (i.e., the double product) is commonly used as an indicator to estimate myocardial oxygen consumption. The production of myocardial energy requires a large supply of oxygen. Myocardial cells extract 65–75% of the oxygen content from the blood, while other tissues in the body extract only 10–25%. Thus, under normal conditions, the myocardium already absorbs nearly the maximum amount of oxygen from the blood. When additional oxygen is needed, it is difficult to extract more from the blood, and the only solution is to increase coronary {|###|} blood flow. Under normal circumstances, the coronary circulation has significant reserve capacity, and its blood flow can vary markedly with physiological conditions. During intense physical activity, the coronary {|###|} artery appropriately dilates, and blood flow can increase to 6–7 times the resting level. During hypoxia, the coronary {|###|} artery also dilates, increasing blood flow by 4–5 times. When atherosclerosis causes coronary {|###|} artery stenosis or partial branch occlusion, its ability to dilate weakens, blood flow decreases, and the blood supply to the myocardium becomes relatively fixed. If the myocardial blood supply is reduced to a level that barely meets the heart's normal needs, there may be no symptoms at rest. However, when the cardiac load suddenly increases—due to exertion, emotional stress, left heart failure, etc.—leading to increased myocardial tension (increased ventricular volume, elevated end-diastolic pressure), increased myocardial contractility (elevated systolic pressure, increased rate of change in ventricular pressure curve), and faster heart rate, myocardial oxygen demand rises. Alternatively, when coronary {|###|} artery spasm occurs (e.g., due to excessive smoking or neurohumoral dysregulation), coronary {|###|} blood flow further decreases. Or, in cases of sudden reduction in circulatory blood flow (e.g., shock, extreme tachycardia), the imbalance between myocardial blood supply and demand deepens, resulting in insufficient myocardial blood supply and triggering angina. In patients with severe anemia, angina may occur even without a reduction in myocardial blood supply, due to insufficient oxygen-carrying capacity caused by reduced red blood cells.

In most cases, exertion-induced angina tends to occur at the same level of "heart rate × systolic blood pressure."The direct cause of pain may be the accumulation of excessive metabolic byproducts in the myocardium under ischemic and hypoxic conditions, such as acidic substances like lactic acid, pyruvic acid, and phosphoric acid, or polypeptide substances similar to kinins. These stimulate the afferent nerve endings of the cardiac autonomic nerves, which transmit signals through the 1st to 5th thoracic sympathetic ganglia and corresponding spinal segments to the brain, generating the sensation of pain. This pain is reflected in the skin areas innervated by spinal nerves at the same level as the autonomic nerve entry points—namely, behind the sternum and the anterior and lateral aspects of both arms, especially the left side, rather than the anatomical location of the heart. Some suggest that abnormal stretching or contraction of the richly innervated coronary vessels in ischemic regions may directly generate pain impulses.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The typical episode of angina pectoris is characterized by a sudden onset of crushing, oppressive, or suffocating pain located behind the upper or middle part of the sternum. It may also involve most of the precordial area and can radiate to the left shoulder, the anteromedial aspect of the left arm, reaching the ring and little fingers. Occasionally, it may be accompanied by a sense of impending doom, often compelling the patient to cease activity immediately. In severe cases, sweating may occur. The pain typically lasts 1–5 minutes and rarely exceeds 15 minutes; it usually subsides within 1–2 minutes (rarely more than 5 minutes) with rest or after taking nitroglycerin tablets. It is often triggered by physical exertion, emotional stress (anger, anxiety, excessive excitement), exposure to cold, overeating, or smoking. Anemia, tachycardia, or shock may also induce it. Atypical angina pectoris may manifest as pain in the lower sternum, left precordial region, or upper abdomen, radiating to the neck, jaw, left scapular region, or right anterior chest. The pain may be brief or present only as a sense of discomfort or tightness in the left anterior chest.

(1) **Exertional Angina Pectoris (Angina Pectoris of Effort)**: This is angina pectoris induced by exercise or other conditions that increase myocardial oxygen demand. It includes three subtypes:

1. **Stable Exertional Angina Pectoris (Stable Angina Pectoris)**: Also known as typical angina pectoris, this is the most common form. It refers to the classic episodes of angina pectoris caused by myocardial ischemia and hypoxia, with no change in its characteristics over 1–3 months. Specifically, the frequency of pain episodes per day or week remains roughly the same, the level of exertion or emotional stress that triggers the pain is consistent, the nature and location of the pain are unchanged, the duration of pain is similar (3–5 minutes, rarely exceeding 10–20 minutes), and the response to nitroglycerin occurs within the same timeframe.

During an episode of this type, the patient appears anxious, with pale, cold, or sweaty skin. Blood pressure may slightly rise or fall, and a systolic murmur (due to mitral papillary muscle dysfunction) may be heard at the cardiac apex. The second heart sound may show paradoxical splitting, and other signs such as pulsus alternans or precordial heave may be present.

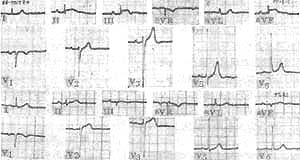

At rest, the electrocardiogram (ECG) of more than 50% of patients is normal. Abnormal ECG findings may include ST-segment and T-wave changes, atrioventricular block, bundle branch block, left anterior or posterior fascicular block, left ventricular hypertrophy, or arrhythmias. Occasionally, evidence of old myocardial infarction may be seen. During a pain episode, the ECG may show typical ischemic ST-segment depression (Figure 2).

**Figure 2: ECG of Stable Angina Pectoris**

The left panel shows 12 leads during an angina episode, with significant ischemic ST-segment depression in V2, V3, V4, V5, and V6, along with a ventricular premature beat in aVR.

The right panel shows 12 leads after the angina episode subsides, with the aforementioned ST-segment changes alleviated.

Chest X-ray may show no abnormalities or reveal cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, etc.

2. **New-Onset Exertional Angina Pectoris (Initial Onset Angina Pectoris)**: This refers to patients who have not previously experienced angina pectoris or myocardial infarction but now develop angina pectoris due to myocardial ischemia and hypoxia, with the onset occurring within the past 1–2 months. Patients who previously had stable angina but have been free of episodes for several months and then experience a recurrence are also sometimes classified under this type.

The nature of this type of colicky pain, possible signs, electrocardiogram and X-ray findings, etc., are the same as those of stable colicky pain, but the onset of colicky pain is still within 1 to 2 months. Most patients later show stable colicky pain, but it may also develop into worsening colicky pain or even myocardial infarction.

3. Worsening exertional angina pectoris Also known as progressive angina pectoris. It refers to patients with previously stable angina pectoris who experience frequent changes in the frequency, severity, and triggering factors of pain within three months, with progressive worsening. The patient's pain threshold gradually decreases, so milder physical activity or emotional agitation can trigger an attack. Consequently, the number of episodes increases, the pain becomes more severe, and the duration of episodes extends, possibly exceeding 10 minutes. Nitroglycerin fails to relieve the pain immediately or completely. During an attack, the ECG shows significant ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion, which resolve afterward without evidence of myocardial infarction.

This type of angina pectoris reflects progression in coronary artery disease and carries a poorer prognosis. It may develop into acute transmural myocardial infarction. Some patients may already have smaller myocardial infarctions (non-transmural) or scattered subendocardial infarcts that are not reflected in the ECG. Sudden death may also occur. However, some patients with long-standing stable angina pectoris may experience a phase of progressive worsening of angina before gradually stabilizing again.

(2) Spontaneous angina pectoris (angina pectoris at rest) The onset of angina is not clearly related to myocardial oxygen demand. Compared with exertional angina, the pain typically lasts longer, is more severe, and is less easily relieved by nitroglycerin. It includes four types:

1. Decubitus angina (angina decubitus) Also known as rest angina. It occurs during rest or deep sleep, with longer and more severe episodes that are not clearly related to physical activity or emotional agitation. It often occurs at midnight, occasionally during naps or rest. The pain is usually intense and unbearable, causing the patient to feel dysphoric and restless, prompting them to get up and move around. The signs and ECG changes are more pronounced than in stable angina, and nitroglycerin is less effective or provides only temporary relief.

This type of angina may develop from stable angina, new-onset angina, or worsening angina, indicating a worsening condition and a very poor prognosis. It may progress to acute myocardial infarction or lead to severe arrhythmias and death. The mechanism remains debated but may involve nocturnal dreams, nighttime blood pressure drops, or undetected left ventricular failure, leading to insufficient perfusion of the myocardium distal to the narrowed coronary artery. Alternatively, lying flat may increase venous return, cardiac workload, and oxygen demand.

2. Variant angina pectoris (Prinzmetal's variant angina pectoris) The nature of angina in this type is similar to decubitus angina, also often occurring at night. However, the ECG during an attack shows ST-segment elevation in the affected leads (Figure 3), with corresponding ST-segment depression in other leads (other types of angina generally show ST-segment depression in all leads except aVR and V1). Sufficient evidence now confirms that this type of angina is caused by coronary artery spasm superimposed on preexisting stenosis, leading to myocardial ischemia. However, patients with normal coronary angiography may also experience this type of angina due to coronary artery spasm, possibly related to α-adrenergic receptor stimulation. These patients are at risk of myocardial infarction sooner or later.

Figure 3 ECG of variant angina pectoris

The two lines above show ST segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, with slight ST segment depression in aVL, and increased T waves in V2, V3, V5, and V6 during an episode of colicky pain.

The changes mentioned above disappear after the episode of colicky pain.

3. Intermediate syndrome (intermediate syndrome), also known as coronary insufficiency (coronary insufficiency), refers to colicky pain caused by myocardial ischemia that lasts longer, ranging from 30 minutes to over an hour. The episodes often occur during rest or sleep, but electrocardiograms, radionuclide scans, and serological tests show no evidence of myocardial necrosis. The nature of this type of pain lies between colicky pain and myocardial infarction and is often a precursor to myocardial infarction.

4. Postinfarction angina (postinfarction angina) refers to colicky pain that occurs shortly after or weeks following an acute myocardial infarction. Due to the blockage of the coronary artery supplying blood, myocardial infarction occurs, but the myocardium is not completely necrotic. A portion of the non-necrotic myocardium remains in a state of severe ischemia, leading to recurrent pain, with the constant risk of another infarction.

(3) Mixed-type angina pectoris (mixed type angina pectoris) involves the combined occurrence of exertional and spontaneous colicky pain. This results from fixed reductions in coronary artery blood flow reserve due to coronary artery lesions, coupled with transient further reductions. It exhibits the clinical manifestations of both exertional and spontaneous colicky pain. Some believe this type of angina is quite common in clinical practice.

In recent years, the term unstable angina pectoris (unstable angina pectoris) has been widely used in clinical settings to describe the intermediate state between stable angina pectoris and acute myocardial infarction or sudden death. It includes newly onset, worsening exertional angina, and various types of spontaneous angina. The pathological basis involves coronary artery intimal hemorrhage, rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, platelet or fibrin aggregation, and coronary artery spasms superimposed on preexisting lesions.

Based on the occurrence of colicky pain during exertion, the severity of angina can be classified into four grades: ① Grade I: No symptoms during daily activities. More strenuous physical activities than usual, such as light jogging on flat ground, quickly climbing three flights of stairs while carrying heavy objects, or ascending steep slopes, provoke colicky pain. ② Grade II: Slight limitation in daily activities. Ordinary physical activities, such as walking 1.5–2 kilometers at a normal pace, climbing three flights of stairs, or ascending slopes, provoke colicky pain. ③ Grade III: Significant impairment in daily activities. Less strenuous physical activities than usual, such as walking 0.5–1 kilometer at a normal pace, climbing two flights of stairs, or ascending small slopes, provoke colicky pain. ④ Grade IV: Minimal physical activity (e.g., slow walking indoors) provokes colicky pain. In severe cases, colicky pain may occur even at rest.

Based on typical attack characteristics and signs, relief after taking nitroglycerin, combined with age and the presence of coronary heart disease risk factors, and excluding other causes of cardiac colicky pain, a diagnosis can generally be established. During an attack, an electrocardiogram (ECG) may show ST-segment depression, flat or inverted T waves in leads dominated by the R wave (in variant angina, the corresponding leads show ST-segment elevation), with gradual recovery within minutes after the attack. For patients with no ECG changes, a stress test may be considered. For atypical attacks, the diagnosis relies on observing the efficacy of nitroglycerin and ECG changes during the attack. If the diagnosis remains uncertain, repeated ECG tests, stress tests, or 24-hour dynamic ECG monitoring can be performed. If the ECG shows positive changes or the stress test induces an angina attack, the diagnosis can be confirmed. For difficult cases, radionuclide imaging or selective coronary artery angiography may be performed. For patients considered for surgical treatment, selective coronary artery angiography is mandatory. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) of the coronary arteries can reveal lesions in the vessel wall, which may be more helpful for diagnosis (Figures 1A, B). Coronary angioscopy may also be considered.

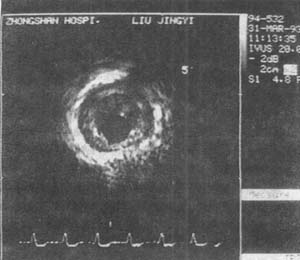

Figure 1A Intravascular ultrasound cross-sectional imaging of the coronary artery

The image shows fibrous plaque lesions of atherosclerosis in the left anterior descending coronary artery. The outermost ring with the strongest ultrasound reflection is the outer layer of the vessel wall, while the innermost ring with the weakest reflection is the arterial wall media. The arterial intima shows concentric thickening with fibrous plaques.

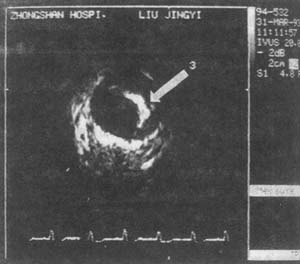

Figure 1B Intravascular ultrasound cross-sectional imaging of the coronary artery

The image shows calcified plaque lesions of coronary atherosclerosis. The arrows indicate strongly reflective calcified plaques, whose posterior acoustic shadowing disrupts the integrity of the vessel wall imaging.

In China, the manifestations of angina attacks in patients are often atypical. Therefore, caution is required when determining whether chest discomfort or pain is angina. In recent years, foreign scholars have also emphasized that the term "angina" does not fully represent pain, as patients' perception of myocardial ischemia and hypoxia may involve sensations other than pain, leading them to deny feeling pain. The following aspects can aid in the clinical identification of angina.

(1) Nature: Angina should be characterized by crushing, oppressive, suffocating, heavy, or dull pain, rather than sharp, knife-like, or stabbing pain, brief needle-like or electric shock-like pain, or continuous chest tightness lasting all day. In fact, it is not necessarily "pain." In a few patients, it may manifest as a burning sensation, tension, or shortness of breath accompanied by a tight squeezing sensation in the throat or upper trachea. The pain or discomfort usually starts mildly, gradually intensifies, and then subsides, rarely affected by changes in posture or deep breathing.

(2) Location: The pain or discomfort is often located in the sternum or its vicinity, but it can also occur anywhere from the upper abdomen to the throat, though rarely above the throat. Sometimes it may be felt in the left shoulder or arm, occasionally in the right arm, jaw, lower cervical spine, upper thoracic spine, or between or above the left scapula. However, it is rarely located in the left axilla or lower left chest. Patients often use their entire palm or fist to indicate the distribution of pain or discomfort, rarely pointing with a single fingertip.

(3) Duration: Typically 1–15 minutes, mostly 3–5 minutes, occasionally up to 30 minutes (excluding intermediate syndrome). Pain lasting only a few seconds or discomfort (mostly a dull sensation) persisting all day or for several days is unlikely to be angina.

(4) Precipitating Factors The primary precipitating factor is physical exertion, followed by emotional agitation. Activities such as climbing stairs, brisk walking on level ground, walking after a heavy meal, walking against the wind, or even minor actions like straining during bowel movements or raising the arms above the head can trigger symptoms. Exposure to cold environments, consuming cold beverages, pain in other parts of the body, and emotional changes like fear, tension, anger, or anxiety can also induce symptoms. The pain threshold is lower in the morning, so mild exertion such as brushing teeth, shaving, or walking may trigger an episode. In contrast, the pain threshold rises in the late morning and afternoon, meaning even more strenuous activities may not provoke symptoms. Discomfort that occurs after physical activity rather than during the activity itself is less likely to resemble colicky pain. The combination of physical exertion and emotional stress further increases the likelihood of triggering symptoms. Spontaneous colicky pain may occur without any obvious precipitating factors.

(5) Effects of Nitroglycerin

If sublingual nitroglycerin is effective, the colicky pain of the heart should be relieved within 1 to 2 minutes (though it may take up to 5 minutes in some cases, considering that patients might inaccurately estimate time). Nitroglycerin may be ineffective for supine-type colicky pain of the heart. When evaluating the effects of nitroglycerin, it is also important to consider whether the medication used by the patient has expired or is nearing expiration.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

(1) Treatment during an attack

1. Rest: Rest immediately when an attack occurs. Symptoms usually subside once the patient stops activity.

2. Medication: For more severe attacks, fast-acting nitrate preparations can be used. These drugs not only dilate the coronary arteries, reduce resistance, and increase blood flow, but also reduce venous return, ventricular volume, intracardiac pressure, cardiac output, and blood pressure by dilating peripheral blood vessels, thereby decreasing the heart's preload and afterload as well as myocardial oxygen demand, thus relieving angina.

⑴ Nitroglycerin: A 0.3–0.6mg tablet can be placed under the tongue for sublingual absorption, dissolving rapidly in saliva. It begins to take effect in 1–2 minutes and lasts about half an hour. It is effective for approximately 92% of patients, with 76% experiencing relief within 3 minutes. Delayed or no effect may indicate that the patient does not have coronary heart disease or has severe coronary heart disease, or that the medication has expired or failed to dissolve. In the latter case, the patient can be instructed to chew the tablet lightly and continue sublingual absorption. Long-term repeated use may reduce efficacy due to tolerance, but effectiveness can be restored after a 10-day discontinuation. Spray and capsule formulations are also available in recent years. Side effects include dizziness, headache, throbbing sensation in the head, facial flushing, palpitations, and occasionally a drop in blood pressure. Therefore, patients should lie flat when using the medication for the first time, and oxygen may be administered if necessary.

⑵ Isosorbide dinitrate (for angina relief): 5–10mg can be taken sublingually, with effects appearing in 2–5 minutes and lasting 2–3 hours. Alternatively, a spray formulation can be used, with 1.25mg per spray, taking effect in 1 minute.

⑶ Amyl nitrite: A highly volatile liquid stored in small ampoules (0.2ml each). To use, wrap the ampoule in a handkerchief, crush it, and immediately inhale through the nose. It acts quickly but briefly, starting in 10–15 seconds and lasting only a few minutes. Its effects are similar to nitroglycerin but with a more pronounced blood pressure-lowering effect, so caution is advised. Another similar preparation is octyl nitrite.

While using the above medications, sedatives may also be considered.

(2) Treatment during remission

Efforts should be made to avoid all known factors that may trigger an attack. Adjust dietary habits, especially avoiding overeating; abstain from smoking and alcohol. Modify daily routines and workload; reduce mental stress; maintain appropriate physical activity, but avoid levels that induce pain symptoms. Generally, bed rest is unnecessary. For patients with initial episodes (new-onset), worsening or more frequent attacks (unstable angina), or those with variant angina, intermediate syndrome, or post-infarction angina—suspected as a precursor to myocardial infarction—a period of rest is recommended.

Long-acting antianginal medications should be used to prevent angina attacks. The following long-acting drugs can be used alone, alternately, or in combination:

1. Nitrate preparations

⑴ Isosorbide dinitrate: Take 5–10mg orally three times daily. Effects begin within half an hour and last 3–5 hours. Isosorbide mononitrate can be taken at 20mg twice daily.{|111|}⑵ Pentaerythritol tetranitrate: Take 10–30mg orally three to four times daily. Effects begin in 1–1½ hours and last 4–5 hours.

(3) Long-acting nitroglycerin preparations: Long-acting tablets allow nitroglycerin to be released continuously and slowly. They take effect within half an hour after oral administration and can last for 8–12 hours. They can be taken every 8 hours, with each dose being 2.5 mg. Applying 2% nitroglycerin ointment or membrane tablets (containing 5–10 mg) to the skin of the chest or upper arm may maintain the effect for 12–24 hours.

2. Beta-adrenergic blockers (β-blockers) These drugs block the stimulatory effects of sympathomimetic amines on heart rate and myocardial contractility receptors, slowing the heart rate, lowering blood pressure, reducing myocardial contractility and oxygen consumption, thereby alleviating the onset of colicky pain. Additionally, they reduce the hemodynamic response during exercise, decreasing myocardial oxygen consumption at the same level of physical activity. They also constrict small resistance vessels (stirred pulse) in non-ischemic myocardial areas, thereby allowing more blood to flow into ischemic regions through highly dilated collateral circulation (delivery vessels). The dosage should be high. Adverse effects include prolonged ventricular ejection time and increased cardiac volume, which may exacerbate myocardial ischemia or induce heart failure. However, their effect of reducing myocardial oxygen consumption far outweighs these adverse effects. Commonly used preparations include: ① Propranolol, 3–4 times/day, 10mg each time, gradually increasing the dose to 100–200mg/day. ② Oxprenolol, 3 times/day, 20–40mg each time. ③ Alprenolol, 3 times/day, 25–50mg each time. ④ Pindolol, 3 times/day, 5mg each time, gradually increasing to 60mg/day. ⑤ Sotalol, 3 times/day, 20mg each time, gradually increasing to 240mg/day. ⑥ Metoprolol, 50–100mg twice daily. ⑦ Atenolol, 25–75mg twice daily. ⑧ Acebutolol, 200–400mg/day. ⑨ Nadolol, 40–80mg once daily, etc.

β-blockers can be used in combination with nitrates, but the following should be noted: ① β-blockers and nitrates have synergistic effects, so the dose should be relatively small, especially at the beginning, to avoid adverse reactions such as orthostatic hypotension. ② When discontinuing β-blockers, the dose should be gradually reduced, as abrupt withdrawal may induce myocardial infarction. ③ They are not suitable for patients with cardiac insufficiency, bronchial asthma, or bradycardia. Their side effect of slowing the heart rate limits the increase in dosage.

3. Calcium channel blockers These drugs inhibit calcium ions from entering cells and also block the utilization of calcium ions in the excitation-contraction coupling of myocardial cells. Thus, they suppress myocardial contraction, reduce myocardial oxygen consumption, dilate coronary arteries (stirred pulse), relieve coronary artery spasm, and improve blood supply to the subendocardial myocardium. They also dilate peripheral blood vessels, lower arterial pressure, reduce cardiac load, decrease blood viscosity, inhibit platelet aggregation, and improve myocardial microcirculation. Commonly used preparations include: ① Verapamil, 80–120mg three times daily; sustained-release formulation, 240–480mg once daily. Adverse effects include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, bradycardia, prolonged PR interval, and hypotension. ② Nifedipine, 10–20mg three times daily, can also be taken sublingually; sustained-release formulation, 30–80mg once daily. Adverse effects include headache, dizziness, lack of strength, hypotension, and increased heart rate. ③ Diltiazem, 30–90mg three times daily; sustained-release formulation, 90–360mg once daily. Adverse effects include headache, dizziness, and insomnia. Newer preparations include nicardipine, 10–20mg three times daily; nisoldipine, 20mg twice daily; amlodipine, 5–10mg once daily; felodipine, 5–20mg once daily; and bepridil, 200–400mg once daily.

Calcium channel blockers are most effective in treating variant angina pectoris. This class of drugs can be taken together with nitrates, among which nifedipine can also be combined with β-blockers. However, there is a risk of excessive cardiac suppression when verapamil or diltiazem is used concomitantly with β-blockers. When discontinuing this class of medications, it is advisable to gradually reduce the dosage before stopping to avoid coronary artery spasm.

4. Coronary artery vasodilators Vasodilators that can dilate coronary arteries theoretically increase coronary blood flow, improve myocardial blood supply, and relieve angina. However, due to the complex pathological conditions of coronary arteries in coronary heart disease, some vasodilators, such as dipyridamole, may dilate non-diseased or grade I lesions far more significantly than grade III lesions, reducing collateral blood flow and causing the so-called "coronary steal phenomenon." This increases blood supply to normal myocardium while further reducing blood supply to ischemic myocardium, hence they are no longer used to treat angina. Currently used vasodilators include: ① Molsidomine, 1–2 mg, 2–3 times/day; adverse effects include headache, flushing, and gastrointestinal discomfort. ② Amiodarone, 100–200 mg, 3 times/day, also used for treating rapid arrhythmias; adverse effects include gastrointestinal reactions, drug rash, corneal pigmentation, bradycardia, and thyroid dysfunction. ③ Efloxate, 30–60 mg, 2–3 times/day. ④ Carbocromen, 75–150 mg, 3 times/day. ⑤ Oxyfedrine, 8–16 mg, 3–4 times/day. ⑥ Aminophylline, 100–200 mg, 3–4 times/day. ⑦ Papaverine, 30–60 mg, 3 times/day, etc.

(三)Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment Based on the principles of pattern identification and treatment in traditional Chinese medicine, both symptomatic and root treatments are employed. Symptomatic treatment, mainly applied during the pain phase, focuses on "unblocking" through methods such as promoting blood circulation, resolving stasis, regulating qi, warming yang, and resolving phlegm. Root treatment, generally applied during remission, emphasizes balancing yin and yang, regulating the zang-fu organs, and harmonizing qi and blood, including methods like tonifying yang, enriching yin, replenishing qi and blood, and regulating the zang-fu organs. Among these, the "invigorating blood and resolving stasis" method (commonly using Salvia, Carthamus, Sichuan Lovage Rhizome, Typha, Curcuma Root, etc.) and the "aromatic warming and unblocking" method (commonly using Styrax Pill, Su Bing Drop Pill, Kuanxiong Pill, Baoxin Pill, Musk Baoxin Pill, etc.) are the most frequently used. Additionally, acupuncture or acupoint tuina therapy also shows certain efficacy.

(四)Other Treatments Low-molecular-weight dextran or hydroxyethyl starch injection, 250–500 ml/day, administered intravenously for 14–30 days as a course, aims to improve microcirculatory perfusion and can be used for frequent angina attacks. Anticoagulants such as heparin, thrombolytics, and antiplatelet drugs may be used to treat unstable angina. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy increases systemic oxygen supply and may improve refractory angina, though the effects are difficult to sustain. Enhanced external counterpulsation may increase coronary blood supply and can also be considered. For patients with early heart failure, fast-acting digitalis preparations should be used alongside angina treatment.

(五)Surgical Treatment The primary surgical procedure is coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), using the patient’s own great saphenous vein or internal mammary artery as bypass graft material. One end is anastomosed to the aorta, and the other end is anastomosed to the distal segment of the diseased coronary artery, directing aortic blood to improve myocardial blood supply. Preoperative selective coronary angiography is performed to assess the extent and severity of coronary lesions, aiding in surgical planning (including determining the number of grafts). Currently, in countries with high coronary heart disease prevalence, this surgery has become the most common elective cardiac procedure. Multiple grafts can be performed in a single operation, and it is considered highly effective in relieving angina.

This surgery is indicated for: ①Left coronary artery main stem lesions; ②Stable angina pectoris with poor response to medical treatment, affecting work and life; ③Worsening angina pectoris; ④Variant angina pectoris; ⑤Intermediate syndrome; ⑥Post-infarction angina pectoris. The degree of coronary artery stenosis should exceed 70% lumen obstruction, the distal lumen of the stenotic segment should be patent, and left ventricular function should be relatively good.

Postoperative angina symptoms can improve in 80-90% of cases, with 65-85% of patients experiencing an enhanced quality of life. However, it remains uncertain whether the surgery can improve ventricular function, prevent severe arrhythmias, heart failure, or myocardial infarction in the future, or prolong the patient's lifespan. Additionally, the surgery itself may lead to complications such as myocardial infarction, and the transplanted vessels may become occluded postoperatively. Therefore, surgical indications should be strictly controlled. Among these, patients with left main coronary artery lesions or complete occlusion of the right coronary artery combined with over 70% occlusion of the left anterior descending branch are generally considered to have the strongest surgical indications, as the procedure may prolong their lifespan.

(6) Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA) A balloon-tipped catheter is inserted through a peripheral artery and guided into the coronary artery with the assistance of a conductive wire to reach the narrowed segment. The balloon is then inflated with contrast medium to dilate the stenosis. In eligible patients, this procedure can achieve results comparable to surgical intervention. Ideal candidates include: ① Patients with angina (duration <1 year) who respond poorly to drug therapy and experience impaired health; ② Patients with single-vessel coronary artery disease, where the lesion is proximal, non-calcified, and non-spastic; ③ Patients with objective evidence of myocardial ischemia and preserved left ventricular function and collateral circulation. If PTCA fails, emergency coronary artery bypass grafting may be required. In recent years, PTCA has also been used to treat multi-vessel coronary disease and post-myocardial infarction angina, though it is contraindicated in patients with left main coronary artery lesions. The immediate success rate of PTCA is around 90%, but 25-35% of patients experience restenosis within 3-6 months postoperatively.

(7) Other Coronary Artery Interventional Therapies Due to the high restenosis rate following PTCA, alternative interventional methods such as laser coronary angioplasty (PTCLA), coronary atherectomy, coronary rotablation, and intracoronary stent placement have been developed to reduce restenosis. Preliminary results indicate that, except for stents, these methods have not significantly lowered the restenosis rate.

(8) Exercise Therapy A carefully structured and appropriately paced exercise regimen can promote the development of collateral circulation, improve exercise tolerance, and alleviate symptoms.

Most patients, especially those with stable angina, experience symptom relief or disappearance after treatment. With sufficient collateral circulation established, they may remain pain-free for extended periods. However, some cases of initial-onset angina, worsening angina, decubitus angina, variant angina, and intermediate syndrome may progress to myocardial infarction, which is why they are sometimes referred to as "pre-infarction angina."

Differential diagnosis should consider the following conditions:

(1) Cardiac neurosis (functional disorder) Patients with this condition often complain of chest pain, but it is usually brief (a few seconds) stabbing pain or prolonged (several hours) dull pain. Patients frequently prefer to take deep breaths or sigh, sometimes accompanied by fetid mouth odor. The location of chest pain is often near the left breast or the apex of the heart and may shift frequently. Symptoms typically appear after fatigue rather than during exertion. Engaging in grade I activity may actually provide relief, and some patients can tolerate heavier physical activity without experiencing chest pain or tightness. Nitroglycerin is ineffective or takes more than 10 minutes to "work." Symptoms often include palpitations, fatigue, and other signs of neurasthenia.

(2) Acute myocardial infarction The pain location in this condition is similar to angina pectoris, but the pain is more severe and can last for several hours. It is often accompanied by shock, arrhythmia, heart failure, and fever. Nitroglycerin usually does not alleviate the pain. Electrocardiograms show ST-segment elevation and abnormal Q waves in leads corresponding to the infarcted area. Laboratory tests reveal elevated white blood cell count, serum creatine phosphokinase, aspartate transaminase, lactate dehydrogenase, myoglobin, myosin light chains, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

(3) Syndrome X This condition is caused by dysfunction of small coronary artery vasomotion, primarily manifesting as recurrent exertional angina pectoris, though pain can also occur at rest. During episodes or after stress, electrocardiography may show myocardial ischemia, nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging may reveal defects, and echocardiography may demonstrate segmental wall motion abnormalities. However, this condition is more common in women, with no obvious risk factors for coronary artery disease. The pain symptoms are less typical, coronary angiography is negative, left ventricular hypertrophy is absent, ergonovine testing is negative, treatment response is inconsistent, and the prognosis is good—distinguishing it from coronary artery disease-related angina pectoris.

(4) Angina pectoris caused by other diseases These include severe aortic valve stenosis or regurgitation, coronary arteritis due to rheumatic fever or other causes, syphilitic aortitis leading to coronary ostial stenosis or occlusion, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and congenital coronary artery anomalies. Differentiation relies on other clinical manifestations.

(5) Intercostal neuralgia The pain in this condition typically affects 1–2 intercostal spaces and is not necessarily confined to the anterior chest. It is characterized as stabbing or burning pain, usually persistent rather than episodic. Coughing, deep breathing, or body movement can exacerbate the pain. Tenderness is present along the nerve pathway, and raising the arm may cause local pulling pain, distinguishing it from angina pectoris.

Additionally, atypical angina pectoris must be differentiated from chest or abdominal pain caused by esophageal disorders, diaphragmatic hernia, peptic ulcer disease, intestinal diseases, cervical spondylosis, and other conditions.