| disease | Thymoma |

| alias | Malignant Neoplasm of Thymus |

The thymus is an important immune organ in the human body, originating from the endoderm of the third (or fourth) pharyngeal arch during embryonic development. It is derived from primitive foregut epithelial cells and migrates into the anterior mediastinum as the embryo grows. Thymic tumors, which arise from thymic epithelial cells or lymphocytes, are the most common, accounting for 95% of thymic tumors and ranking first to third among all mediastinal tumors. In a Japanese study of 4,968 mediastinal tumors, thymomas were second only to teratomas, comprising 20.2% of mediastinal tumors. In an American study of 1,064 mediastinal tumors, thymomas ranked first, accounting for 21.14%. Domestic reports often list teratoid tumors as the most common. A comprehensive analysis of 14 domestic studies involving 2,720 mediastinal tumors showed thymomas ranked third, following teratomas and neurogenic tumors, accounting for 22.37%.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

In pathology, thymomas are named based on the cellular components that account for more than 80% of the tumor. They are classified into epithelial cell type and mixed epithelial-lymphocytic type. It is difficult to distinguish benign from malignant thymomas solely based on pathological morphology. A more appropriate classification is invasive and non-invasive thymomas, based on clinical manifestations, macroscopic observations during surgery, and pathological morphological characteristics. However, they are conventionally referred to as benign and malignant thymomas.

The distinction between benign and malignant thymomas requires consideration of clinical manifestations and findings during surgical procedures. During surgery, attention should be paid to: ① whether the tumor has a complete capsule; ② whether the tumor exhibits invasive growth; ③ the presence of distant metastasis or intrathoracic seeding; and ④ cellular atypia under microscopy. A comprehensive analysis is necessary to reach a correct conclusion. Tumors with a complete fibrous capsule, confined growth within the capsule, no adhesion or infiltration to surrounding organs, and easy surgical removal are considered benign or non-invasive thymomas. Tumors that breach the capsule, invade surrounding organs or tissues (such as the pericardium, pleura, lungs, or blood vessels), cannot be completely resected during surgery, or show intrathoracic seeding or pleural metastasis, are classified as malignant or invasive thymomas.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsLike any mediastinal tumor, the clinical symptoms of thymoma arise from compression of surrounding organs and the tumor's own specific symptoms—associated syndromes. Small thymomas often have no clinical complaints and are not easily detected. When the tumor grows to a certain size, common symptoms include chest pain, chest tightness, cough, and discomfort in the anterior chest. The nature of chest pain is nonspecific, varying in intensity and lacking a specific location. Generally, it is mild and often treated symptomatically without further examination. If symptoms persist for a long time, some patients undergo X-ray examinations, or certain patients are found to have a mediastinal mass shadow during routine chest fluoroscopy or radiography. Thymomas that are overlooked at diagnosis often grow to a considerable size by this point, compressing veins or manifesting as superior vena cava obstruction syndrome. Severe chest pain, rapid worsening of symptoms in a short period, intense irritative cough, dyspnea due to pleural effusion, shortness of breath and flusteredness caused by pericardial effusion, and systemic skeletal pain all suggest the possibility of malignant thymoma or thymic carcinoma.

A distinctive feature of thymoma is its association with certain syndromes, such as myasthenia gravis (MG), pure red cell aplasia (PRCA), hypoglobulinemia, nephritis-nephrotic syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, lupus erythematosus, and megaesophagus.

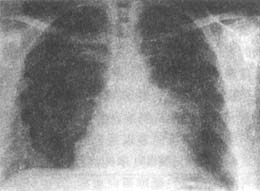

X-ray examination is an important method for detecting and diagnosing mediastinal tumors. On the frontal view of a chest radiograph, thymomas often appear as a widened mediastinum or a round or oval dense shadow protruding into one side of the thoracic cavity, more commonly on the right than the left, and may also protrude into both sides. Protrusion to the left is often obscured by the main aortic arch, while protrusion to the right may overlap with the superior vena cava. The tumor shadow has clear and sharp edges, sometimes lobulated. The lateral view may reveal a homogeneous, solid mass shadow located behind the sternum and in front of the great vessels of the heart (Figures 1, 2). A few thymomas may exhibit linear, punctate, patchy, or amorphous calcifications, with a lower degree of calcification compared to teratomas. Some thymomas appear as flat sheets lying over the great vessels of the heart, making this type the most challenging to diagnose via X-ray examination. Lateral tomography of the lesion is a simple, practical, and economical method for confirming thymomas, as it can reveal the presence, size, and density of the tumor. When more complex examinations are unavailable, lateral tomography is particularly useful.

Chest CT is an advanced and sensitive method for examining mediastinal tumors. It can accurately display the tumor's location, size, whether it protrudes to one or both sides, the tumor's margins, the presence of surrounding infiltration, and the assessment of surgical resectability. For cases undiagnosed by clinical and conventional X-ray examinations, chest CT holds special value (Figures 3–6).

Figure 1 Thymoma

Chest radiograph: Frontal view shows a mass shadow adjacent to the left cardiac border.

Figure 2 Thymoma

Chest radiograph: Lateral view shows the tumor located in the superior mediastinum behind the sternum.

Figure 3 Thymic carcinoma

CT shows erosion and destruction of the vertebral body.

Figure 4 Thymic carcinoma

Chest CT reveals invasion and destruction of the right rib.

Figure 5 Thymic carcinoma

Chest CT: Shows a mass shadow in the left anterior superior mediastinum.

Figure 6 Thymoma with pure red cell aplasia

CT: Clearly displays the tumor's position and its relationship with surrounding organs.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

(1) Principles of Treatment: Thymoma should be surgically removed once diagnosed. The reasons are: continued tumor growth can compress adjacent tissues and organs, leading to significant clinical symptoms; it is difficult to determine the benign or malignant nature of the tumor based solely on clinical and X-ray findings; and benign tumors can also undergo malignant transformation. Therefore, both benign and malignant thymomas should be excised as early as possible. For unresectable malignant thymomas, pathological biopsy can guide postoperative treatment, and partial resection followed by radiotherapy can alleviate symptoms and prolong patient survival.

(2) Incision Selection: For smaller thymomas protruding to one side, an anterior lateral intercostal thoracotomy is often used. For larger tumors protruding bilaterally, a median sternotomy may be employed. In recent years, median sternotomy has been increasingly used, allowing not only the removal of the thymoma but also the contralateral thymus to prevent the future development of myasthenia gravis. Some also opt for a transverse sternotomy with bilateral thoracic incisions for tumor resection. Median sternotomy does not enter the pleural cavity, reducing postoperative respiratory interference and avoiding respiratory complications. Some surgeons remove thymomas via a cervical incision, indicated for elderly patients with contraindications to thoracotomy, small tumors, or tumors located near the neck.(3) Key Considerations During Surgery: Isolated benign thymomas without adhesions can be completely excised without difficulty, allowing smooth completion of the procedure. However, certain Zabing cases require thorough preoperative assessment of potential challenges. For malignant thymomas, exploration must first clarify the tumor's relationship with surrounding structures before dissection. Thymomas are located in the superior mediastinum at the base of the heart, near the junction of the heart and major vessels. Malignant thymomas may infiltrate and adhere to surrounding tissues; as the tumor grows, adjacent structures may be displaced, altering normal anatomical relationships. Fibrous connective tissue adhesions may thicken, making it difficult to distinguish from blood vessels. These factors can lead to accidental vascular injury and major bleeding during surgery, necessitating vigilance.

Assessing tumor resectability is a critical consideration during surgery. If the tumor invades the innominate vein or superior vena cava, or if vessels are encased within the tumor, or if the tumor is frozen to surrounding tissues, a cautious approach should be taken—aborting the procedure, performing only a biopsy, and opting for postoperative radiotherapy. If the tumor adheres to or infiltrates major vessels but remains separable, gradual dissection from superficial to deep, easy to difficult, can be performed to mobilize the tumor before clamping and excising its pedicle.

During dissection, all fibrous tissues or bands should be clamped before transection to avoid vascular injury and surgical complications. If vascular injury occurs unexpectedly, avoid panic and blind clamping for hemostasis. Instead, apply pressure with gauze, prepare suction, accelerate blood transfusion, clear the surgical field, and assess the injury's location and extent before deciding on direct suturing or repair.

If the tumor protrudes from one hemithorax to the other or extends into the neck, dissection should proceed under direct visualization. Some vessels may traverse the tumor or supply it, and blunt dissection may cause bleeding. If the tumor invades the pericardium, the pericardium can be incised in a normal area, and a finger inserted to assist in tumor removal or en bloc resection with the pericardium.

6. Surgical Outcomes: The primary treatment for both benign and malignant thymomas is surgical resection. Radiotherapy is considered only for incomplete or unresectable cases, while chemotherapy has minimal efficacy.

The resection rate correlates with tumor size. Generally, larger tumors have lower resection rates, consistent with general oncological principles. However, tumor size alone is not the sole determinant of resectability. Sometimes, large tumors can be excised, while smaller ones cannot. Beyond size, tumor invasion—particularly into major vessels like the superior vena cava, innominate vein, or aorta—significantly impacts resectability. When tumors encase vessels or are frozen to surrounding structures, even moderately sized tumors may be unresectable.

7. Radiation Therapy for Thymoma Even in cases where malignant thymoma appears to have been completely resected macroscopically, the tumor bed still requires completion. If residual tumor tissue is clearly identified as not completely removed or unresectable during surgery, the dose should be increased, typically to 60Gy (6000rad). Some suggest that even benign thymomas have a small chance of recurrence, so prophylactic irradiation of 30–40Gy (3000–4000rad) is recommended for benign thymomas. The outcomes of radiotherapy for thymoma are generally unsatisfactory, as reported results vary widely across regions, making evaluation difficult.

1. Myasthenia Gravis (MG) It has long been observed that myasthenia gravis is associated with the thymus (or thymoma). Clinically, MG can be divided into three types: eyelid ptosis, prolonged visual fatigue, and diplopia, which constitute the ocular type; inability to sustain arm extension or the need to sit and rest after walking a short distance, which constitute the trunk type; and difficulty chewing and swallowing, or even respiratory muscle paralysis, which constitute the bulbar type. The most dangerous clinical manifestation is myasthenic crisis, where respiratory muscle paralysis necessitates artificial assisted ventilation.

Currently, MG is considered an autoimmune disease, primarily caused by a mutation in the thymus due to certain stimuli, leading to the loss of control over certain forbidden cell clones and allowing their differentiation and proliferation, resulting in an immune response against self-components (striated muscle) and the onset of muscle weakness.

For many years, the treatment of MG has relied on anticholinesterase drugs such as pyridostigmine. In recent years, immunosuppressants such as hormones and cyclophosphamide have also been added.

The surgical indications for MG include patients with or without thymoma who exhibit no symptom relief despite increasing doses of anticholinesterase drugs, or who experience myasthenic crises and recurrent respiratory infections.

2. Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA)

One of the diseases coexisting with thymoma is pure red cell aplasia. PRCA can be primary, with an unclear cause, or secondary to drugs, infections, or tumors. Experimental studies suggest that PRCA is an autoimmune disease, where an unknown trigger leads to an autoimmune reaction against red blood cell antigens, which may be present in the human thymus. The thymoma itself does not directly affect red blood cell growth; instead, it may enhance the immune system's sensitivity, or the thymoma may be induced by a highly sensitive proliferative system.

3. Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritis The relationship between nephrotic syndrome nephritis and thymoma remains unclear. Nephrotic syndrome can be part of the systemic manifestations of certain tumors, such as Hodgkin's disease. A possible explanation is that thymoma and glomerulonephritis form cross-reacting antigen-antibody complexes.

Despite various examinations, clinically challenging cases can still arise. Some have suggested performing superior vena cava or innominate vein angiography, or mediastinal pneumography, but due to the complexity of these procedures, they are rarely used nowadays. Common conditions requiring differentiation from thymoma include teratoma and ascending aortic aneurysm. Teratomas often occur in young and middle-aged adults, may be asymptomatic, or present with recurrent pulmonary infections. A history of coughing up hair or oily substances may sometimes be noted. X-ray examination may reveal teeth or calcified bone shadows within the mass, and cystic teratomas can be confirmed via ultrasound. Literature reports cases where mediastinal tumors were mistaken for ascending aortic aneurysms, or vice versa. On lateral chest radiographs, ascending aortic aneurysms appear as spindle-shaped or round shadows originating from the left ventricle. Fluoroscopy may show expansile pulsations of the mass, and auscultation may reveal murmurs. Two-dimensional ultrasound can detect dilation of the ascending aorta, while color Doppler may show turbulent flow spectra. Chest CT can demonstrate localized aneurysmal dilation of the ascending aorta. When diagnosis is difficult, ascending aortography may be performed. In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has seen increasing clinical application, offering unique value in diagnosing cardiac and major vascular anomalies and vascular tumors. It is a sensitive and effective method for distinguishing mediastinal tumors from ascending (or descending) aortic aneurysms.