| disease | Pilonidal Sinus and Pilonidal Cyst |

| alias | Pilonidal Disease, Pilonidal Sinus and Pilonidal Cyst, Pilonidal Disese |

Pilonidal sinus and Pilonidal cyst, collectively referred to as Pilonidal disease, are a chronic sinus or cyst in the soft tissues of the sacrococcygeal region, characterized by the presence of hair within. It can also present as an acute abscess in the sacrococcygeal area, which may rupture to form a chronic sinus or temporarily heal only to rupture again, leading to recurrent episodes. The cyst is accompanied by granulation tissue and fibrous proliferation, often containing a cluster of hair. Although the condition can be observed after birth, it most commonly occurs between the ages of 20 and 30 during adolescence, when sebaceous gland activity increases, leading to the onset of symptoms.

bubble_chart Etiology

The true cause of the disease is unknown, with two prevailing theories.

(1) Congenital

Due to remnants of the medullary canal or developmental abnormalities of the sacrococcygeal suture leading to skin inclusions. However, precursor lesions of pilonidal disease are rarely found in the midline postanal shallow dimple area in infants, whereas they are more commonly observed in adults.

(2) Acquired

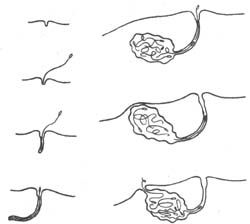

It is believed that sinuses and cysts result from granulomatous diseases caused by injury, surgery, foreign body irritation, and chronic infection. Recent evidence confirms that externally introduced hair is the primary cause of the disease. The intergluteal cleft has a negative suction effect, allowing shed hairs to penetrate the subcutaneous tissue. Excessive or long hairs in the cleft, combined with the filtering and macerating effect of the hair tips on the skin, enable hairs to penetrate the skin, forming short tracts that later deepen into sinuses. Hair roots shedding into the sinus can also cause hair shafts to penetrate. During the disease process, dynamic changes are observed (Figure 2), but hairs are found in only half of the cases. This condition is more common in individuals with excessive hair, overactive sebaceous glands, deep intergluteal clefts, or frequent buttock injuries. The sacrococcygeal skin of truck drivers often suffers from prolonged jolting and injury, leading to the accumulation of sebaceous gland tissue and debris in the cyst, which triggers inflammation. This disease is more prevalent among U.S. Army personnel and is referred to as "Jeep disease." Common pathogens include anaerobic bacteria, staphylococci, streptococci, and large intestine bacilli. Rainsbury and Southan analyzed quiescent pilonidal disease and found that single bacteria accounted for less than half of cases, with anaerobes making up 58%. Surprisingly, staphylococci are uncommon, and most aerobic bacteria are Gram-negative.

Figure 2 Formation and natural evolution of pilonidal sinus

Right image: A small pit in the groove with hairs gradually penetrating;

Right image: More hairs penetrate, and due to secondary inflammation, a skin sinus eventually forms.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

A pilonidal cyst is often asymptomatic without secondary infection, presenting only as a protrusion in the sacrococcygeal region, with some experiencing pain and swelling in the area. Typically, the primary and initial symptom is the occurrence of an acute abscess in the sacrococcygeal region, characterized by local redness, swelling, heat, and pain—hallmarks of acute inflammation. Most cases spontaneously rupture and discharge pus or resolve after surgical drainage, with a minority of drainage openings closing completely. However, most cases manifest as recurrent episodes or persistent

discharge, forming a sinus or fistula. During the quiescent phase of a pilonidal sinus, an irregular small opening can be observed in the midline skin of the sacrococcygeal region, with a diameter of about 1 mm to 1 cm. The surrounding skin is red, swollen, and hardened, often with scarring, and sometimes hair can be seen. A probe can be inserted 3–4 mm, and in some cases up to 10 cm. Squeezing may release thin, foul-smelling fluid. During the acute

stage of attack, there are signs of acute inflammation, tenderness, and redness, with discharge of copious purulent secretions. Abscesses and cellulitis may occasionally occur.

The main diagnostic signs of pilonidal sinus and pilonidal cyst are acute abscess in the sacrococcygeal region or a chronic sinus with secretion, accompanied by local acute inflammatory manifestations. During examination, a pilonidal cavity is observed in the midline position. Pilonidal sinus is easily diagnosed based on symptoms and signs.

(1) Non-surgical therapy

The sacrococcygeal pit does not require treatment, as it is merely a depression at the sacrococcygeal joint, the lower part of the sacrum, and the tip of the coccyx, with no symptoms and no clinical significance.

If infection occurs in sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinuses or sacrococcygeal cysts, anti-inflammatory treatment should be administered, and the local area should be kept clean. If an abscess recurs, incision and drainage should be performed. However, the skin and subcutaneous tissue in the sacrococcygeal region are thick and firm, and early symptoms may not be obvious. Inflammation often spreads to surrounding tissues, causing cellulitis. If deep tissue necrosis occurs, early incision and drainage is necessary.

Sclerotherapy involves injecting a corrosive agent into the sinus to destroy the epithelial lining of the sinus and cyst, causing the cavity and sinus to close. Since 1960, phenol solution injection therapy has been used, though not widely adopted because pure phenol solution causes severe pain. Later, an 80% concentration was used under general anesthesia, and a colloidal substance was injected into the sinus to protect the surrounding skin. Hegge (1987) injected 1–5 ml of 80% phenol solution slowly into the sinus over about 15 minutes to prevent complications such as skin burns, fat necrosis, or severe pain. This method can be repeated every 4–6 weeks. About half of the patients recover after just one injection, while 12% require five or more injections. In a follow-up of 43 patients for over a year, only 3 (6%) experienced recurrence. Stansby (1989) injected 80% phenol solution into the sinus under general anesthesia, left it for 1 minute, and then curetted the sinus, repeating the process three times. Among 104 treated cases, 4 developed sterile abscesses, and 1 had cellulitis, with no other complications. Compared to 65 cases treated with surgical excision, the cure rates were 86% for excision and 75% for phenol injection. With an average follow-up of 8 months (3 months to 4 years), 10 excision cases and 12 injection cases recurred.

Surgery is the primary treatment method, but it is contraindicated during active inflammation and should be performed only after the inflammation subsides. The surgical methods include the following:

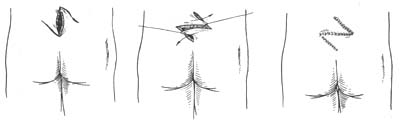

1. Excision with primary [first-stage] suture: The entire lesion, along with the freed muscle and skin, is excised, and the wound is completely sutured for primary healing. To eliminate the deep gluteal cleft and its negative pressure, reducing wound dehiscence, hematoma, and abscess formation, a Z-plasty may be performed (Figure 1). This method is suitable for cysts and small, uninfected midline sinuses, with a recurrence rate of 0–37%. The advantages include a short healing time, soft and mobile scar formation in the gluteal cleft, and the presence of soft tissue between the scar and sacrum, which can withstand injury.

Figure 1: Elliptical incision at the pilonidal sinus site

Left: An elliptical incision is made at the pilonidal sinus site;

Middle: Full-thickness flap separation and transposition;

Right: Skin suturing

2. Partial excision with suture: The lesion is excised, and the skin on both sides of the wound is sutured to the sacral fascia, allowing most of the wound to heal primarily, while the central part heals by granulation tissue. This method is suitable for cases with multiple sinus openings and sinuses, with results similar to excision with primary suture, though the healing time is longer.

3. Excision with open wound and secondary suture: This is suitable for severely infected cases or cases where primary suture leads to infection requiring wound incision and drainage.

4. Excision with open wound: This is used for wounds too large to suture or recurrent cases after surgery. The procedure is simple, but the healing period is long, and the resulting scar is extensive, with only a thin layer of epithelium adhering to the sacrum. If injured, the scar is prone to rupture.

5. Marsupialization: The superficial part of the sinus wall and overlying skin are excised, and the wound edges are sutured with absorbable sutures to promote healing. With careful postoperative care, satisfactory results are often observed. This method is mostly used for non-excisable cases or recurrent pilonidal sinuses.

(3) Results of various treatments

Keighley (1993) analyzed the recurrence rates of seven treatment methods in the literature: ① Open treatment alone: 7–24%; ② Excision and open treatment: 0–22%; ③ Excision and marsupialization: 7–13%; ④ Excision and initial stage [first stage] suture: 1–46%; ⑤ Excision and Z-plasty: 0–10%; ⑥ Excision and water calptrop base peel flap: 3–5%; ⑦ Excision and split-thickness skin grafting: 0–5%.

Cancer arising from a pilonidal sinus is rare, with Phipshen (1981) reviewing the literature and finding only 32 cases. The lesions are mostly well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. Changes in the wound should raise suspicion of malignancy, such as easily ruptured ulcers, rapid growth, bleeding, and a fungoid margin. Wide excision should be the first choice. Due to the extensive wound, skin grafting or flap reconstruction is often required. Inguinal lymphadenopathy should be biopsied to rule out metastasis, as its presence indicates a poor prognosis. The literature reports a 5-year survival rate of 51%, with a recurrence rate of approximately 50%. At initial diagnosis, metastasis to the inguinal lymph nodes is found in 14% of cases.

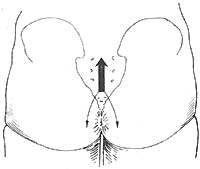

It should be differentiated from boils, anal fistulas, and granulomas. Boils grow on the skin, protrude from it, and have a yellow tip. Carbuncles have multiple external openings with necrotic tissue inside. The external opening of an anal fistula is close to the anus, the fistula tract runs toward the anus, a cord-like structure can be felt on palpation, and there is an internal opening in the anal canal, with a history of anorectal abscess. In contrast, the direction of a pilonidal sinus is mostly cranial and rarely downward (Figure 3). Subcutaneous node granulomas are connected to the bone, and X-ray examination reveals bone destruction, with subcutaneous node sexually transmitted disease lesions in other parts of the body. Syphilitic granulomas have a history of syphilis and positive syphilis serum reactions.

Figure 3 The direction of the pilonidal sinus

Note: 93% of sinuses exit the skin pit and run cranially; 7% may run downward around the anus.