| disease | Pulmonary Echinococcosis |

| alias | Pulmonary Echinococcosis, Pulmonary Hydatid Cyst, Pulmonary Hydatid Cyst, Pneumocystosis |

Pulmonary echinococcosis (pulmonary hydatid cyst, pulmonary echinococcosis, pulmonary hydatid cyst) is caused by the larvae (hydatid) of Echinococcus granulosus (dog tapeworm) in the lungs, and is a relatively common parasitic disease in the lungs, which is zoonotic. This disease is most common in pastoral areas, occurring almost worldwide, especially in Australia, New Zealand, South America, etc. In China, it is mainly distributed in provinces and regions such as Gansu, Xinjiang, Ningxia, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, and Tibet.

bubble_chart Pathogen

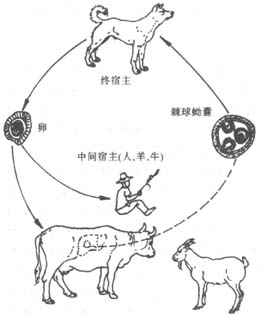

The definitive host of Echinococcus granulosus. Adult Chinese Taxillus Herb resides in the small intestine of dogs. Eggs are excreted with feces and contaminate food. After ingestion by humans (or sheep, pigs, cattle), the eggshell is digested by gastric acid in the upper consumptive thirst digestive tract, hatching into larvae, namely oncospheres, which then penetrate the digestive tract membrane and enter the bloodstream, reaching the portal venous system (mesenteric membrane, greater omentum, and liver). Most larvae remain in the liver (approximately 75–80%). A small number of oncospheres pass through the liver into the pulmonary circulation (about 8–15%) and other organs, such as the mesenteric membrane, omentum, spleen, pelvis, muscles, subcutaneous tissue, etc. (See Figure 1 for the life cycle of Echinococcus).

After entering the lungs, the oncospheres gradually develop into hydatid cysts, reaching 1–2 cm in size after about six months. Due to the loose lung tissue, rich blood circulation, and the negative pressure of the thoracic cavity, the growth rate of oncospheres in the lungs is faster than in the liver and kidneys, increasing by 1–2 times the original volume annually on average, reaching about 2–6 cm. The largest cysts can grow up to 20 cm, with cyst fluid weighing over 3000 g. Hydatid cysts consist of an outer and inner capsule. The inner capsule is the inherent wall of the hydatid cyst, only 1 mm thick but with a high pressure of 13.3–40 kPa (100–300 mmHg), making it prone to rupture. The inner capsule can be further divided into two layers: the inner layer is the germinal layer, which is very thin, secretes colorless transparent cyst fluid, and produces many daughter cysts and Chinese Taxillus Herb scolexes. If detached into the cyst cavity, they become hydatid sand. The outer layer is acellular, multilayered, translucent, milky white, elastic, and resembles rice noodles in appearance. The outer capsule is a fibrous membrane formed by the host tissue in response to the inner capsule, enveloping the entire inner capsule and about 3–5 mm thick. There is a potential space between the inner and outer capsules, containing no fluid or gas, and no adhesion.

Figure 1: Life cycle of Echinococcus

Approximately 80% of pulmonary hydatid cysts are peripheral, with the right lung more commonly affected than the left, and the lower lobes more than the upper lobes. The right lung has slightly more blood flow and is closer to the liver, with abundant lymphatic connections between them, which may explain its higher incidence. Most cysts are solitary (65–75%), while multiple cysts usually number 2–3, either unilateral or bilateral. About 17–22% are complicated by cysts in other locations, with concurrent lung and liver involvement being the most common (13–18%).

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

The pathological changes of pulmonary echinococcosis, apart from the cyst itself, mainly involve the mechanical compression exerted by the large cyst on the lung, leading to atrophy and fibrosis of the surrounding lung tissue, as well as congestion or inflammation. Cysts larger than 5 cm can cause bronchial displacement, luminal narrowing, or necrosis of the bronchial cartilage, eventually rupturing into the bronchus. Superficial pulmonary hydatid cysts may induce reactive pleuritis, while large cysts can rupture into the pleural cavity, releasing numerous protoscoleces and forming multiple secondary hydatid cysts. Central cysts may occasionally erode and rupture large blood vessels, causing massive hemorrhage. A few hydatid cysts may calcify. If the cyst ruptures into the small bronchi, air may enter between the inner and outer layers of the cyst, resulting in various radiographic signs. Infected or ruptured cysts may be complicated by pleural or mediastinal abscesses or empyema. Rupture of hepatic hydatid cysts may lead to communication with the pleural cavity, lungs, or bronchi, forming pulmonary hydatid cyst-biliary-bronchial fistulas.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsAccording to a large-scale case analysis in China from 1950 to 1985, pulmonary echinococcosis accounted for 14.81% (2408/16258) of human echinococcosis cases, with males outnumbering females (approximately 2:1). Children comprised 25–30% of cases, while the majority were under 40 years old, with the youngest being 1–2 years old and the oldest 60–70 years.

The interval between infection and symptom onset is generally 3–4 years, or even 10–20 years. Symptoms vary depending on the size, number, location of the cysts, and the presence of complications. In the early stages, small cysts usually cause no obvious symptoms and are often discovered during physical examinations or chest X-rays for other conditions. When cysts enlarge and cause compression or complications such as inflammation, symptoms like cough, sputum production, chest pain, and hemoptysis may occur. Large cysts or those near the hilum may lead to dyspnea. If the esophagus is compressed, dysphagia may occur. Cysts in the apex of the lung may compress the brachial plexus and cervical sympathetic ganglia, causing Pancoast syndrome (pain in the shoulder and arm on the affected side) and Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, flushing, and anhidrosis on one side). If a cyst ruptures into a bronchus, a large volume of cyst fluid may pose a risk of suffocation, while spilled daughter cysts and protoscolices can form multiple new cysts. Patients often experience allergic reactions, such as skin flushing, urticaria, and wheezing, with severe cases potentially leading to shock. If the ruptured cyst becomes infected, symptoms like fever, yellow sputum, pulmonary inflammation, or lung abscess may occur. A few cysts rupture into the pleural cavity, causing fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, and allergic reactions.

Most patients show no obvious positive signs, though large cysts may cause mediastinal displacement, and in children, chest deformities may develop. On the affected side, dullness on percussion and weakened breath sounds may be observed, while signs of pleurisy or empyema may also be present.bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

Chest X-ray examination is the primary diagnostic method for echinococcosis. In endemic areas, a definitive diagnosis can often be made based on the chest X-ray alone for individuals with a history of exposure. In the early stages, cysts smaller than 1 cm in diameter show only indistinct inflammatory shadows at the margins. Cysts larger than 2 cm appear as well-defined, sharply outlined round or oval shadows with uniform but slightly faint density, lower than that of the heart or solid tumors. By the time a definitive diagnosis can be made, the cysts typically measure 6–10 cm, with a density close to that of solid tumors. They are usually solitary, though multiple cysts may occur (Figure 2). As fluid-filled cysts, they exhibit the "hydatid respiration sign" under fluoroscopy: during inspiration in an upright position, the diaphragm descends, slightly increasing the cephalocaudal diameter, while during expiration, the diaphragm rises, and the transverse diameter becomes slightly longer while the vertical dimension shortens. Large cysts may appear lobulated or multilocular. Cysts in the lower lung fields "sit" on the diaphragm, causing it to descend or even become indented. In some cases, an artificial pneumoperitoneum may be required to shift the mediastinum to the contralateral side. Cysts in the lower lobes minimally affect the mediastinum, whereas large cysts at the dome of the right liver can significantly displace the heart to the left, a feature helpful for differential diagnosis. A few cases may present with atelectasis and pleuritis.

Figure 2 Bilateral multiple hydatid cysts

The chest X-ray shows multiple round, sharply marginated, uniformly dense shadows.

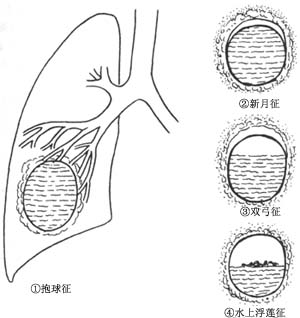

If the cyst erodes and penetrates a small bronchus, allowing a small amount of air to enter between the inner and outer layers, specific radiographic signs may appear (Figure 3): ① A small amount of air between the inner and outer layers forms a crescent-shaped lucency at the upper part of the cyst on an upright film ("crescent sign"). ② If more air enters the inner layer, a fluid level appears, with two arcuate shadows representing the inner and outer layers above it ("double-arch sign"). ③ When the inner layer ruptures and collapses, the crumpled inner layer floats on the fluid surface, showing irregular shadows on the fluid level ("water-lily sign").

Figure 3 Schematic diagram of radiographic signs of pulmonary hydatid cysts

If the cyst ruptures, its contents are coughed up, and no infection occurs, the chest X-ray may show a thin-walled, smooth-marginated air-filled cyst. Over time, the cavity gradually shrinks, leaving only some fibrotic shadows. If infection occurs after rupture, the cyst wall thickens, and chronic inflammatory changes may manifest as patchy lung infiltrates. If the cyst ruptures into the pleural cavity, pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax may occur.

The diagnosis of most uncomplicated pulmonary echinococcosis is not difficult, mainly based on: ① A history of residence in endemic areas and contact with animals such as dogs or sheep. ② The X-ray manifestations of echinococcosis are relatively typical, showing single or multiple cyst shadows with sharp edges. ③ Laboratory tests: Eosinophils are increased, usually around 5–10%, and can even reach 20–30%, with a direct count of (0.15–0.3)×109/L. Sometimes, cyst fragments, scolices, or hooks can be detected in coughed-up material or pleural fluid. ④ Other diagnostic methods include immunological tests such as the hydatid intradermal test (Casoni test), hydatid complement fixation test, and indirect hemagglutination test.

Currently, percutaneous or transbronchial biopsy or cytological examination under X-ray or ultrasound guidance is frequently performed for pulmonary mass shadows. However, it is important to note that suspected hydatid cysts should not be punctured to avoid cyst fluid leakage, which may lead to severe complications such as allergic reactions or dissemination of echinococcosis.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The primary treatment is surgical resection, with no specific drugs available. Currently, trials include mebendazole and albendazole, which can cause degeneration of the germinal layer and protoscoleces. Some clinical efficacy has been observed, with symptom improvement and partial cyst stagnation or shrinkage. Praziquantel has shown unclear clinical effects but may be used preoperatively to reduce postoperative recurrence. Currently, drug therapy is only for patients with multiple cysts who cannot undergo surgery. Pulmonary hydatid cysts generally grow progressively, with very few cases of "self-healing." Most will eventually rupture due to increased intracystic pressure, leading to severe complications. Therefore, timely diagnosis and surgery are essential.

The main surgical methods are cystectomy and lobectomy. The surgical approach depends on cyst size, number, location, presence of complicating infections, and pleural adhesions. During surgery, care must be taken to prevent cyst rupture and spillage of cyst fluid into the pleural cavity or chest wall soft tissues to avoid disseminated echinococcosis or allergic reactions.

**Anesthesia:** Generally, general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation is used. Double-lumen intubation is unnecessary unless specifically required, as unilateral lung collapse is not needed during surgery. For larger cysts, difficult double-lumen intubation may increase the risk of cyst rupture during manipulation. There is also a risk of cyst rupture before removal, with potential aspiration of cyst fluid or fragments into the respiratory tract, requiring caution.

**Incision:** For lung resection, a posterolateral thoracotomy is typically performed, entering through the 5th intercostal space or rib bed for easier hilar access.

For simple cyst removal, an incision is made closer to the cyst.

**Surgical Methods:**

1. **Complete Cystectomy:** After thoracotomy and adhesion separation, since cysts are often near the periphery, a fibrin layer may be visible on the lung surface. Before removal, pack the surrounding lung with gauze, exposing only the incision site. Prepare a high-suction aspirator to promptly remove contents if accidental rupture occurs, avoiding pleural contamination. Carefully incise the outer fibrous layer of the cyst with a slightly angled blade to avoid direct penetration into the inner cyst. Due to high intracystic pressure, a small incision in the outer cyst will cause the white inner cyst wall to protrude. Extend the incision and have the anesthesiologist inflate the lung to push the inner cyst out. Since the inner and outer cysts are usually non-adherent, the cyst can often be removed intact. After removal, any bronchial fistulas on the outer cyst are first packed with gauze, then sutured. Excess residual cavity walls can be excised or inverted before closure to eliminate the cavity completely.

2. **Puncture and Aspiration Cystectomy:** Surround the cyst with gauze soaked in hydrogen peroxide to kill protoscoleces. Formaldehyde was previously used but is now avoided due to the risk of severe bronchospasm if it enters bronchial fistulas. Any bronchial fistulas in the residual cavity must be sutured, followed by layered closure (for larger cavities) to eliminate the cavity.

3. **Lung Resection:** Used for ruptured cysts, severe lung infection, bronchiectasis, pulmonary fibrosis, empyema, bronchopleural fistula, or suspected lung cancer. If possible, isolate and clamp the bronchus first to prevent cyst rupture into the bronchus during manipulation, which could cause dissemination or asphyxia.

4. **Management of Special Types of Echinococcosis:** For simultaneous liver and lung cysts, a single surgery may suffice. For bilateral disease, address the larger or more complicated side first. For pulmonary cysts with bronchopleural fistula, perform closed drainage first, followed by lung resection after infection control and recovery.

**Treatment Outcomes:** In 1979, Qian Zhongxi reported a 0.9% mortality rate for thoracic surgery, with no recent fatalities. Surgical outcomes are generally good, with rare recurrences due to: ① Residual small hydatid cysts left during surgery. ② Intraoperative cyst fluid spillage and protoscolex dissemination. ③ Reinfection. Recurrent cases often respond well to repeat lung resection.