| disease | Chronic Salpingo-oophoritis |

In the acute phase of salpingo-oophoritis, if treatment is delayed or incomplete, it can become chronic over time. A small number of cases may have less virulent pathogens or stronger host resistance, leading to mild or absent symptoms that go unnoticed or are misdiagnosed, resulting in delayed treatment. However, with the availability of powerful antibiotics today that can effectively treat acute salpingo-oophoritis, the likelihood of acute cases progressing to chronic sexually transmitted disease foci has significantly decreased. Only subcutaneous node infections generally follow a chronic sexually transmitted disease course.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

The pathological types of chronic salpingo-oophoritis can generally be divided into four categories: hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx, adnexal inflammatory mass, and interstitial salpingitis.

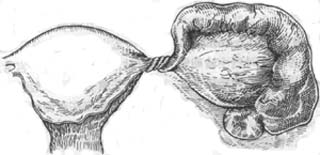

(1) Hydrosalpinx and tubo-ovarian cyst: Hydrosalpinx is caused by inflammation of the tubal membrane leading to fimbrial occlusion, with exudate accumulating in the lumen to form an abdominal mass. Some cases originate as pyosalpinx, where the pus is gradually absorbed and liquefies over time, turning into a serous fluid and evolving into hydrosalpinx. If the original condition was a tubo-ovarian abscess, it may develop into a tubo-ovarian cyst (hydrosalpinx). Additionally, sometimes perioophoritis can obstruct follicular rupture, leading to the formation of follicular cysts, or bacteria may invade during follicular rupture, creating inflammatory effusion that later connects with hydrosalpinx to form a tubo-ovarian cyst. Hydrosalpinx is usually not very large, typically under 15 cm in diameter, and, like pyosalpinx, assumes a retort-like shape. Tubo-ovarian hydrosalpinx can reach diameters of 10–20 cm. Both conditions are seen in cases where inflammation has not recurred for many years. The surface is smooth, and the tubal wall becomes thin and translucent due to distension. Hydrosalpinx often has fine membranous adhesions to the pelvic peritoneum, though some cases remain free. Due to significant distal enlargement, torsion of the hydrosalpinx (Figure 1) may occasionally occur, with the proximal end (isthmus) as the axis, more commonly on the right side. Hydrosalpinx is frequently bilateral (Photo 1). The uterine end may sometimes be loosely occluded, so during hysterosalpingography, X-ray fluoroscopy or imaging may reveal the typical appearance of hydrosalpinx. A few patients report sudden large or intermittent small amounts of watery discharge from the vagina, possibly due to increased pressure in the hydrosalpinx cavity forcing fluid through the loosely occluded tubal ostium. Pelvic examination after significant vaginal discharge may reveal the disappearance of the original mass.

Figure 1 Torsion of hydrosalpinx

Photo 1 Bilateral hydrosalpinx

(2) Pyosalpinx and tubo-ovarian abscess: If pyosalpinx persists without resolution, it may undergo repeated acute episodes. Especially when closely adhered to pelvic intestines, E. coli infiltration can lead to secondary mixed infections. When the body's resistance weakens, residual pyosalpinx may also be triggered by external factors, such as excessive fatigue, sexual activity, or gynecological examinations, leading to acute episodes. Local congestion before or after menstruation may also cause recurrence. Due to repeated episodes, the tubal wall becomes highly fibrotic and thickened, adhering to adjacent organs (uterus, posterior leaf of the broad ligament, sigmoid colon, small intestine, rectum, pelvic floor, or pelvic sidewall). If stabilized after treatment, the pus may liquefy to form hydrosalpinx or become increasingly viscous, gradually replaced by granulation tissue, with occasional calcification or cholesterol stones.

(3) Adnexal inflammatory mass (adenexitis): Chronic salpingo-oophoritis may lead to inflammatory fibrosis and hyperplasia, forming a firm inflammatory mass. Generally small, if adhered to intestines, greater omentum, uterus, pelvic peritoneum, bladder, etc., it may form a large mass. Such masses can also develop after pelvic inflammatory disease surgery, centered around preserved organs such as the ovary or part of the fallopian tube, pelvic connective tissue, or uterine stump, with intestines and greater omentum adhering to them. Once a chronic inflammatory mass forms, achieving complete resolution of inflammation or total disappearance of the mass becomes quite difficult.

(4) Chronic interstitial salpingitis: This is a chronic inflammatory lesion left by acute interstitial salpingitis, often coexisting with chronic oophoritis. Bilateral fallopian tubes may appear thickened and fibrotic, with small residual abscesses in the muscular layer or beneath the serosa. Clinically, it manifests as thickened adnexa or cord-like thickening. Microscopic examination reveals widespread infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells in all layers of the fallopian tube (Photo 2). Additionally, a condition known as nodular salpingitis of the isthmus may develop, which is a remnant of chronic inflammatory lesions in the fallopian tube. The lesions are mainly confined to the isthmus of the fallopian tube. In such cases, distinct nodules appear in the isthmus, which can sometimes be quite large, resembling small fibroid tumors of the uterine cornu. Microscopically, the muscular layer is abnormally thickened, and the mucosal folds may be separately embedded into the muscular layer, resembling endometriosis. However, it can be distinguished by the absence of endometrial stroma. In some cases, the muscular layer shows infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Photo 2 Chronic salpingitis

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

(1) Abdominal pain: Varying degrees of pain in the lower abdomen, mostly a dull discomfort, accompanied by soreness, distension, and a dragging sensation in the lower back and sacral region, often worsening with fatigue. Due to pelvic adhesions, there may be bladder or rectal pain during filling or emptying, or other bladder/rectal irritation symptoms such as urinary frequency or tenesmus.

(2) Menstrual irregularities: The most common manifestations are frequent menstruation and excessive menstrual flow, likely due to pelvic congestion and ovarian dysfunction. Chronic inflammation can lead to uterine fibrosis, incomplete uterine involution, or abnormal uterine positioning caused by adhesions, all of which may contribute to hypermenorrhea.

(3) Infertility: Damage to the fallopian tubes, resulting in obstruction, often leads to infertility, with secondary infertility being more common.(4) Dysmenorrhea: Pelvic congestion may cause static blood-related dysmenorrhea, typically starting as abdominal pain about one week before menstruation, worsening as the period approaches, and persisting until menstrual flow begins.

(5) Others: Symptoms such as increased leucorrhea, dyspareunia, gastrointestinal disturbances, lack of strength, reduced work tolerance, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and depression may also occur.

(6) Signs:

1. Abdominal examination: Aside from mild tenderness (Grade I) in both lower quadrants, few other positive findings are usually present.

2. Gynecological examination: The uterine cervix often shows erosion and eversion, with mucopurulent leucorrhea. The uterus is frequently retroverted or retroflexed, with reduced mobility compared to normal. Movement of the cervix or uterine body typically causes pain. In mild cases, only thickened, cord-like fallopian tubes may be palpated in the bilateral adnexa. In severe cases, irregular, fixed masses of varying sizes may be felt on either side of the pelvis or posterior/lateral to the uterus, often tender. Thick-walled, adherent cystic masses are usually abscesses, while thin-walled, tense, and slightly mobile masses are more likely hydrosalpinx.

If the above symptoms appear after acute inflammation of the pelvic reproductive organs, chronic adnexitis can be considered. Even without a history of acute sexually transmitted disease, the presence of this series of symptoms can strongly suggest the condition. If examination reveals only slight thickening of the parametrial tissues without masses, a tubal patency test can be performed. If the test confirms tubal obstruction, the diagnosis of chronic salpingitis can be essentially established.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

If the patient has no severe discomfort, non-surgical treatment should be administered. Even if symptoms are more pronounced, an integration of Chinese and Western medicine comprehensive treatment should be attempted first. With appropriate treatment, recovery is still possible, and there is potential for another pregnancy.

(1) Non-surgical treatment:

Adequate rest and reduced sexual activity are recommended. Thorough treatment of cervicitis, as well as inflammation of the vulva, vagina, and urethral glands—especially cervical erosion—can prevent repeated infections of the adnexa and the possibility of acute episodes. Additionally, the following methods may be selected:

1. Antibiotic therapy is best applied locally, such as through lateral fornix block or intrauterine injection:

(1) Antibiotic lateral fornix block: Depending on the condition, administer once daily or every other day, with 7–8 sessions constituting one course. If necessary, repeat the injections after the next menstruation, generally requiring 3–4 courses. Dexamethasone or prednisolone may also be added to the injection.

(2) Intrauterine and fallopian tube antibiotic injection: The procedure is the same as for fallopian tube hydrotubation. Alternatively, a double-lumen rubber catheter may be inserted into the uterine cavity, with the injection volume gradually increased based on uterine size and the degree of fallopian tube obstruction. The initial dose should not exceed 10 ml, and the injection solution should not be below room temperature to avoid causing fallopian tube spasms. The pressure should be less than 21.3 kPa, with a slow injection rate of 1 ml per minute. After injection, maintain the rubber tube for 15–20 minutes before removal, and advise the patient to rest quietly for half an hour. Begin treatment 3–4 days after the menstrual period ends, administer every 2–3 days, with 5–6 sessions constituting one course, totaling 3–4 courses.

In addition to penicillin and gentamicin, hyaluronidase, chymotrypsin, or dexamethasone should be added. Hyaluronidase hydrolyzes hyaluronic acid in tissues to accelerate drug penetration and absorption, thereby enhancing efficacy. Chymotrypsin dissolves fibrin, clearing necrotic tissue, hematomas, and other secretions.

Adrenal corticosteroids are often combined with antibiotics to treat chronic salpingitis. Reports indicate that injecting antibiotics alone into the fallopian tube lumen achieves patency in 10% of cases, while adding dexamethasone increases this to over 50%. Currently, prednisone is often administered for two cycles before injection: starting from the fifth day of each cycle, take prednisone 20 mg/d for 5 days, gradually reducing to 15 mg/d for 5 days, then 10 mg/d for 10 days, totaling 20 days. Intrauterine injection is performed after the third menstrual period ends. For the first three sessions, use 800,000 U penicillin, 160,000 U gentamicin, and 1,500 U hyaluronidase (or 5 mg α-chymotrypsin) dissolved in 10 ml saline. For the next three sessions, switch to 5 mg dexamethasone with antibiotics. After two courses, rest for one month before repeating injections until patency is achieved.

2. Physical therapy: Promotes blood circulation to facilitate inflammation resolution. Common methods include ultrashort wave, diathermy, and infrared irradiation.

3. Chinese medicinals: Such as Kangfu Xiaoyan Suppository may be used.

(2) Surgical treatment

1. Pyosalpinx or tubo-ovarian abscesses are prone to acute episodes and should be surgically removed. Generally, after controlling inflammation with medication for several days, surgery can proceed regardless of whether the body temperature has normalized. After lesion removal, residual inflammatory lesions are easily controlled, and patients recover more quickly.

2. For chronic inflammatory masses and other chronic fallopian tube lesions, if non-surgical treatment is ineffective, clinical symptoms are severe, and the condition significantly impacts the patient’s life and work—especially for patients over 40—surgical treatment may be considered. Antibiotics should be administered before and after surgery, typically for 3 days preoperatively and 5–7 days postoperatively. Surgery should be thorough, with total hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy offering the best prognosis. Preserving part of the ovary or uterus may lead to recurrence of inflammation. Therefore, for younger patients, non-surgical treatment should be prioritized. Once surgery is decided, it should be thorough; otherwise, the prognosis may be poor. For young patients who urgently desire fertility and have fallopian tube obstruction without mass formation, fallopian tube recanalization surgery should be considered.

(1) Differential diagnosis from old ectopic pregnancy: The medical histories of the two conditions differ. Old ectopic pregnancy often presents with a short delay in menstruation, sudden lower abdominal pain accompanied by symptoms of internal bleeding such as nausea, dizziness, or even syncope, which may subside on its own and even allow a return to normal life. Subsequently, there are repeated episodes of sudden abdominal pain. After an episode, there may be dull pain and a sensation of heaviness, a self-perceived mass in the lower abdomen, and persistent slight vaginal bleeding, all of which differ from chronic adnexitis. Additionally, the patient may appear anemic. On bimanual examination, the mass is often located on one side, firm yet elastic, highly irregular in shape, and less tender than inflammatory masses. A definitive diagnosis can be made by aspirating old blood or small clots through culdocentesis.

(2) Differential diagnosis from endometriosis: Sometimes, differentiation is difficult because both conditions share signs such as dysmenorrhea, heavy menstruation, dyspareunia, dyschezia, infertility, pelvic masses, and adhesions, leading to confusion. A detailed history reveals that the dysmenorrhea in endometriosis is progressive, becoming increasingly severe, starting before menstruation and peaking during menstruation, often persisting for several days afterward. It is typically associated with primary infertility and lacks a history of increased leucorrhea or inflammation. On bimanual examination, the adnexa are thickened and adherent to the posterior wall of a retroverted uterus. The presence of tender nodules on the uterosacral ligaments facilitates diagnosis, though this sign is often absent. Uterine salpingography or laparoscopy can be performed to establish the correct diagnosis.