| disease | Prolapse of Uterus |

| alias | Uterine Prolapse |

The uterus descends from its normal position along the vagina, with the external os of the cervix reaching below the level of the ischial spine, or even the entire uterus protruding outside the vaginal orifice, which is called uterine prolapse. Uterine prolapse is often accompanied by bulging of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

bubble_chart Etiology

The injury to the cervix, cardinal ligaments, and uterosacral ligaments caused by childbirth, along with the failure of supportive tissues to return to normal after childbirth, are the primary reasons. Among 2,504 cases of uterine prolapse in Jinan City, 58.21% occurred in women with 1 to 3 deliveries.

Additionally, during the puerperium period, many parturients prefer lying on their backs and are prone to chronic urinary retention, which can cause the uterus to assume a retroverted position. When the uterine axis aligns with the vaginal axis, increased abdominal pressure can cause the uterus to descend along the vaginal direction, leading to prolapse.

Postpartum habits such as squatting during labor (e.g., washing diapers or vegetables) can also increase abdominal pressure, contributing to uterine prolapse.

In nulliparous women, uterine prolapse occurs due to underdeveloped supportive tissues of the reproductive organs.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Prolapse of uterus refers to the downward displacement of the uterus along the vagina (Figure 2). Based on the degree of prolapse, it can be divided into three grades (Figure 3):

Figure 2 Prolapse of uterus

Figure 3 Grading of uterine prolapse

Grade I: The body of the uterus descends, with the cervical os located between the ischial spine and the vaginal opening. During vaginal examination, the cervical os is within 4 cm from the vaginal opening.

Grade II: The cervix protrudes outside the vaginal opening, while the body or part of the body of the uterus remains within the vagina. However, due to the broad range included, in mild cases only the cervix protrudes outside the vaginal opening, while in severe cases, the elongated cervix and the entire vaginal wall may prolapse outside the vaginal opening.Grade II prolapse of uterus is further divided into mild and severe subtypes.

Mild Grade II: The cervix and part of the anterior vaginal wall are everted and prolapse outside the vaginal opening.

Severe Grade II: The cervix and part of the uterine body, along with most or all of the anterior vaginal wall, are everted and prolapse outside the vaginal opening (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Grade II prolapse of uterus, also demonstrating examination method

Grade III: The entire uterine body and cervix, along with the entire anterior vaginal wall and part of the posterior vaginal wall, are everted and prolapse outside the vaginal opening (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Grade III prolapse of uterus, also demonstrating examination method

The diagnosis is primarily based on signs. Additionally, a certain degree of examination should be performed. Instruct the patient to refrain from emptying the bladder and assume the lithotomy position. During the examination, first ask the patient to cough or strain to increase abdominal pressure, observing whether urine leaks from the urethral opening to determine the presence of stress urinary incontinence. Then, empty the bladder and proceed with the gynecological examination.

First, observe the condition of vaginal wall prolapse and uterine prolapse without exertion. Also, note the status of the vulva and the degree of perineal laceration.

Use a vaginal speculum to inspect the vaginal walls and cervix for any ulceration or the presence of a rectouterine pouch hernia.During the vaginal examination, pay attention to the condition of the levator ani muscles on both sides, determine the width of the levator ani muscle gap, the position of the cervix, and then ascertain the size of the uterus, its position in the pelvic cavity, and whether there is any inflammation or tumor in the adnexa.

Finally, instruct the patient to exert abdominal pressure, and if necessary, assume a squatting position to allow for palpation of the uterine prolapse again, in order to determine the degree of uterine prolapse.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Patients with prolapse of uterus should adopt an integration of Chinese and Western medicine, combining treatment, nutrition, and rest. Treatment methods can be divided into: using uterus support, oral Chinese medicinals, acupuncture, fumigation and washing, and other non-surgical therapies, as well as surgical repair. Since surgery may affect future vagina childbirth, it is only suitable for severe cases and women who no longer plan to conceive.

1. Uterus Support Therapy

(1) Uterus Support and Its Function: Uterus supports have long been used to treat prolapse of uterus. Through continuous improvements in the prevention and treatment of prolapse of uterus across various provinces and cities, better results have been achieved. This method is simple, easy to implement, and allows patients to manage it themselves, making it widely welcomed by rural patients. It can be used for all degrees of prolapse of uterus. There are many types of uterus supports, with the most commonly used being plastic mushroom-shaped supports. Based on the size of the tray, they are divided into large, medium, and small sizes (with diameters or transverse diameters of 6, 5, and 4 cm, respectively). The trays are further divided into round and oval shapes, with the medium size being the most frequently used. The handle is about 5 cm long and curved forward to match the curvature of the vagina.

The uterus support therapy works by using the pubococcygeal muscle bundle of the levator ani to support the uterus tray at the vaginal vault, preventing the descent of the uterus neck and maintaining it at the level of the ischial muscles, with the handle flush with the vaginal opening. For mild cases, no additional support is needed. However, if the vagina is overly relaxed, a menstruation belt may be used to support the handle, or a strap or plastic rope can be attached to the top of the handle and fixed to a waistband to prevent it from falling out.(2) Selection of Support Size: It is advisable to choose a size slightly larger than the genital (pubococcygeal muscle) gap. Generally, the transverse diameter of the gap is most commonly 4 cm, so the medium-sized uterus support is often used. Over time, the pubococcygeal muscle gradually regains its elasticity, the edema of the prolapsed tissue subsides, and the weight decreases, allowing the uterus to no longer prolapse.

(3) Duration of Use: Typically, the support is inserted in the morning before labor and removed in the evening, then washed. It is best not to use it during menstruation. Plastic supports have a smooth surface, are resistant to acid and alkali, and cause minimal irritation to tissues. After insertion, symptoms disappear, enabling patients to engage in various activities without discomfort. Combining it with acupuncture and Chinese medicinals can yield even better results.

Severe cases of prolapse of uterus with excessive vaginal relaxation are not suitable for support therapy.

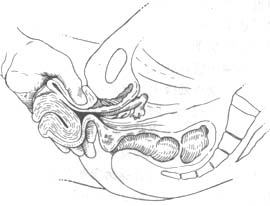

(4) Insertion Method: First, wash hands thoroughly. The patient should lie semi-recumbent on a bed or squat on the ground with legs apart. Hold the handle of the support and position it near the perineal anus, then insert the tray horizontally into the vagina. For oval-shaped supports, insert the narrow end first into the vaginal opening, gradually rotating the handle upward until the entire tray is inside the vagina. Then, rotate the handle so its curvature faces forward (Figure 1).

|

|

|

| (1) Insertion of uterus support | (2) After insertion of uterus support |

Figure 1 Placement of uterus support

(5) Removal: Before sleep, pinch the handle with fingers, pull outward while pressing toward the anus, and the tray will slide out of the vagina. Wash the support with warm water, dry it, and store it properly for reuse.

(6) Precautions for Using Uterus Support:

1. Patients must be taught how to insert and remove the pessary by themselves, and instructed to take it out and clean it every night. For elderly individuals without sexual activity, it is also advisable to remove the pessary every 2-3 days, clean it, and then reinsert it to avoid prolonged placement, which may cause vaginal inflammation. If the pessary stem or plate causes friction, it may lead to vaginal ulcers, forming a vaginal scar ring, which can result in the uterine pessary becoming incarcerated. In severe cases, the pessary plate may cause pressure necrosis, perforating the bladder or rectum, leading to urinary or fecal fistulas.

2. For first-time users, it is necessary to hold the pessary handle during defecation to prevent it from falling out, or to remove the pessary before defecation and reinsert it afterward. After prolonged use, as the uterus gradually ascends, the pessary will not fall out during defecation.

3. Follow-up examinations should be conducted at 1, 3, and 6 months after pessary insertion. After insertion, edema and keratinization of the uterine cervix and vaginal walls disappear, and the degree of prolapse decreases. It is advisable to replace the pessary with a smaller size in a timely manner to avoid difficulty in insertion and removal or the risk of pessary incarceration.

(7) Complications of uterine pessaries and their management: The most common complication is pessary incarceration. In elderly women, the vaginal epithelium is atrophic and fragile, unable to withstand friction. Additionally, elderly women are not sexually active, and although they are instructed to remove and clean the pessary regularly, patients often neglect this if they experience no discomfort. Over one to several months, the vaginal walls may become abraded, ulcerated, and eventually heal into a narrow ring, leading to pessary incarceration. Prolonged pressure may result in pressure necrosis, with the pessary tray penetrating into the bladder, forming a urinary fistula, or compressing the rectum posteriorly, causing necrosis and leading to a rectovaginal fistula. If pessary incarceration is detected, prompt surgical intervention is required to incise the scar ring and remove the pessary. If a urinary or fecal fistula has already developed, the pessary should be removed first, and repair surgery should be performed only after local inflammation is fully controlled.

If the pessary tray has embedded into the bladder, it must be removed via abdominal or extraperitoneal bladder incision. If there is no local inflammation, fistula repair can be performed simultaneously. If inflammation is present, repair should be delayed until the inflammation resolves. If the pessary tray has penetrated the rectum, it can usually be retrieved by probing with a finger through the anus, which is generally not difficult.

II. Surgical Treatment

The choice of surgical procedure should be based on the pathogenesis and anatomical changes of uterine prolapse, considering the following factors:

(1) The site and degree of prolapse.

(2) The position and size of the uterus, and whether the cervix is hypertrophied or elongated, and to what extent.

(3) The width and elasticity of the levator ani muscle gap.

(4) The patient’s age and general health condition. Elderly and frail patients Nan Jing are not suitable for complex surgeries.

(5) Whether fertility needs to be preserved. For women of childbearing age who already have children, sterilization should be considered.

(6) Whether sexual function needs to be preserved.

(7) The presence of concurrent stress urinary incontinence.

Although there are many surgical approaches, they can generally be categorized into the following types:

(1) Shortening the relaxed cardinal ligaments to improve uterine support.

(2) Correcting uterine morphological abnormalities. If the cervix is elongated or hypertrophied, partial cervical resection is necessary to restore normal cervical length.

(3) Shortening the pubovesical cervical fascia to strengthen the support of the external genital tract wall.

(4) Suturing the levator ani muscle gap to reconstruct a functional perineal body.

Common surgical procedures include anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair, perineal repair, and partial cervical resection. These procedures are relatively simple and effective, suitable for most cases of uterine prolapse. Another option is transvaginal hysterectomy combined with anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair and perineal repair.

Over the years, maternal and child health work has developed rapidly. Various regions have established labor protection systems for women, including five-stage healthcare and maternity leave. Family planning has been vigorously promoted, and prolapse of the uterus has become rare. Preventive measures should continue to be strengthened to further reduce the incidence of this disease.

1. Actively promote scientific childbirth: Continuously improve the skills of midwives, promptly suture perineal and vaginal lacerations, and correctly handle difficult deliveries.

2. Vigorously promote postpartum care: Encourage postpartum exercises, ensure adequate rest within three months after delivery, and avoid prolonged squatting, carrying, or lifting heavy objects. Maintain smooth bowel and bladder movements, and promptly treat chronic bronchitis, diarrhea, and other conditions that increase abdominal pressure. Breastfeeding should not exceed two years to prevent atrophy of the uterus and its supporting tissues.

3. Strengthen labor protection for women: Based on women’s physiological characteristics, constitution, age, farming seasons, types of farm work, and job categories, reasonably arrange and utilize female labor.

1. Submucous fibroid: The cervical os cannot be found on the prolapsed mass. The anterior rectal wall does not prolapse. The uterine cervix can be palpated by inserting a hand into the vagina.

2. Cervical elongation: Mostly occurs in nulliparous women. The anterior rectal wall does not prolapse. The anterior and posterior fornices are very high. The uterine body remains within the pelvic cavity, but the cervix is extremely elongated, appearing columnar and protruding outside the vaginal orifice.

3. Chronic uterine inversion: The uterine os cannot be found on the mass, but depressions corresponding to the openings of the fallopian tubes can be identified. The surface is covered with red mucosa and bleeds easily. A rectovaginal-abdominal examination reveals an empty pelvic cavity, and the uterine body cannot be palpated.

4. Vaginal wall cyst or fibroid: Often misdiagnosed as cystocele or uterine prolapse. Upon examination, the uterus is found in its normal position or displaced upward by the mass, and the mass is unrelated to the cervix.