| disease | Acute Salpingo-oophoritis |

| alias | Acute Tubooophoritis |

Salpingitis is the most common type of inflammation in the pelvic reproductive organs. The ovaries are adjacent to the fallopian tubes, and the spread of salphingitis can lead to oophoritis. When oophoritis and salpingitis occur together, it is referred to as salpingo-oophoritis or adnexitis. Sometimes, despite severe inflammatory lesions in the fallopian tubes, the nearby ovaries may remain unaffected. Oophoritis rarely occurs alone. However, the mumps virus has a particular affinity for the ovaries and can cause isolated oophoritis through hematogenous infection. Salpingo-oophoritis most commonly occurs during the reproductive years, with the highest incidence between ages 25 and 35. It is rare in adolescent girls before or after puberty and in menopausal women.

bubble_chart Etiology

(1) During menstruation, after late abortion, or in the puerperium period, the physiological defense functions of the female reproductive tract against infection weaken. The normal acidity of the vagina is altered by menstrual blood or lochia; the cervical canal exhibits grade I dilation or laceration, and the mucus plug disappears; after the normal uterine membrane sheds, the surface of the uterine cavity is exposed, and the dilated blood sinuses and blood clots provide an ideal environment for bacterial growth. The uterus during the puerperium period also has reduced resistance to infection. Therefore, if hygiene is neglected during menstruation or sexual activity occurs, bacteria can easily ascend through the mucous membrane, causing infection of the tubal membrane. This is the most common cause and route of infection. Clinically, cases of acute adnexitis caused by reduced body resistance due to lower abdominal exposure to cold or prolonged work in cold water during menstruation may also be encountered.

(2) Gonococcal infection is the leading cause of acute salpingo-oophoritis in some countries. In recent years, such cases have also been reported in China, so attention should be paid to this condition in patients with gonococcal infection.(3) The spread of subcutaneous node bacilli to the fallopian tubes is primarily through the bloodstream. Other infectious diseases, such as suppurative tonsillitis, diphtheria, mumps, cold-damage disease, paracold-damage disease, and scarlet fever, may occasionally disseminate pathogens via the bloodstream, leading to acute adnexitis.

(4) Inflammatory lesions in organs adjacent to the fallopian tubes, such as appendicitis or colonic diverticulitis, may spread directly to the fallopian tubes through contact.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

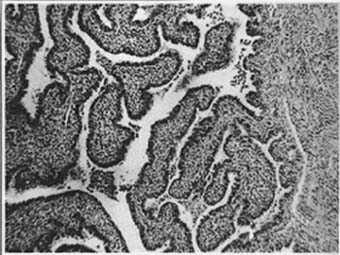

(1) Ascending infection from the genital tract mucosa spreads to the tubal mucosa, causing salpingitis, mucosal edema, and the discharge of serous or purulent exudate. Initially, the inflammatory lesions are limited to the mucosal layer, but the inflammation quickly extends to all layers of the fallopian tube, with the serosal layer being the last affected. The serosa loses its luster and develops fibrin deposits—perisalpingitis. At this stage, the fallopian tube becomes swollen, congested, reddened, and coiled. When mucosal blood vessels are severely congested, a bloody exudate containing a large number of red blood cells may appear, termed hemorrhagic salpingitis. As the inflammation worsens, the tubal lumen fills with a large amount of purulent discharge. Due to inward invasion of the tubal abdominal ostium and adhesions of the fimbriae, the tube becomes occluded. This pathological change prevents pus from flowing into the abdominal cavity, averting further spread of inflammation and avoiding conditions like pelvic peritonitis. The uterine end of the fallopian tube, due to severe mucosal swelling, also becomes blocked, obstructing communication with the uterine cavity.

Photo 1 Acute Salpingitis

(2) Pyosalpinx. Occlusion of both ends of the fallopian tube leads to the accumulation of pus within the tubal lumen, which increases as the inflammatory lesions progress, forming pyosalpinx. The ampulla of the fallopian tube has a thin muscular layer and is highly distensible, whereas the isthmus has a thicker muscular layer and is less prone to dilation. As a result, the pyosalpinx takes on a retort-like shape, gradually expanding toward the ampulla, with a maximum diameter of 12–15 cm. Concurrently, the fallopian tube elongates and descends behind the broad ligament. The contents may be seropurulent or mucopurulent. Pyosalpinx often adheres to surrounding tissues and organs, such as the posterior leaf of the broad ligament, ovary, sigmoid colon, ileum, and sometimes descends into the uterorectal pouch, adhering to the peritoneum there. At this stage, the fallopian tube thickens into a dense, tough cystic mass.

If the bacteria are highly virulent and the inflammatory lesions continue to progress, the increasing pus accumulation may cause the distended and thinned fallopian tube to perforate or rupture, leading to pelvic peritonitis or diffuse peritonitis. Occasionally, the pus may perforate into the rectum, posterior vaginal fornix, or, rarely, the bladder.

Microscopic observation: The mucosa is normal or exhibits grade I inflammatory infiltration. The muscular layer becomes markedly thickened due to edema and leukocyte infiltration, and the serosal layer often develops some degree of acute fibrinous peritonitis.

(4) During the acute phase of salpingitis, the ovary becomes infected either through direct spread of inflammation from the serosal surface or via lymphatic dissemination in the mesosalpinx and mesovarium. In the former case, the inflammatory response is limited to exudate and fibrin formation on the ovarian surface, enveloping the essentially normal ovary within adhesions of surrounding inflamed tissue. If the inflammation is severe and invades the ovarian parenchyma, multiple abscesses may develop, particularly prone to invading mature follicles or newly formed corpora lutea, resulting in follicular-luteal abscesses. These multiple abscesses may coalesce to form an ovarian abscess. Ovarian abscesses often communicate with tubo-ovarian abscesses, forming tubo-ovarian abscesses, which are the most common type of pelvic abscess.

(5) Acute salpingo-oophoritis mostly involves both sides, with one side possibly being less affected. Unilateral salpingo-oophoritis is occasionally seen in cases where inflammation from appendicitis or diverticulitis directly spreads to the adnexa. In rare instances of puerperium infection, unilateral adnexal infection may occur, and in some cases, a large pyosalpinx may form on one side while the other remains unaffected.

During the acute phase of salpingitis, the pelvic peritoneum often exhibits grade I infection with serous effusion. In severe cases, suppurative transformation may occur, leading to the formation of pus. The pus may accumulate as an abdominal mass in the rectouterine pouch (Figure 1), where a tense and painful mass can be palpated through the posterior vaginal fornix. A rectouterine pouch abscess may also originate directly from an infected fallopian tube. If the fimbriated end is not occluded, pus from the fallopian tube may discharge into the abdominal cavity, forming an abdominal mass deep in the pelvis.

Figure 1: Rectouterine pouch abscess

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms usually appear within two weeks after infection, starting with systemic symptoms such as general lack of strength and loss of appetite. The onset is marked by high fever (39–40°C), rapid pulse (110–120 beats per minute), and possible aversion to cold or shivering. Severe pain occurs in both lower abdominal regions, worsening during bowel movements. Sometimes, there may also be painful urination, abdominal distension and fullness, and constipation. The presence of mucus in stool is a sign of inflammatory infiltration irritating the colon wall. Hypermenorrhea, prolonged menstruation, menstrual irregularities, and purulent leucorrhea are common.

Signs: The patient appears acutely sexually transmitted disease, with a flushed face, dry tongue, and thick white coating. Abdominal tenderness, especially in the lower abdomen, is pronounced, with guarding, rigidity, and marked rebound tenderness. There may also be tympanites.

Gynecological examination: The vagina may contain purulent or bloody discharge, and the cervix often shows varying degrees of redness and swelling. In cases of gonococcal infection, pus may be visible or expressible from the openings of the Bartholin’s gland ducts, urethra, and external cervical os. Movement of the cervix during bimanual examination causes severe pain. Due to the patient’s pain sensitivity and abdominal muscle tension, assessing pelvic conditions is often difficult. If the uterus can be palpated, it is usually fixed, of normal or slightly enlarged size, and extremely tender. Bilateral adnexal tenderness is widespread, and adnexal masses are generally hard to discern.

Patients with acute salpingo-oophoritis may sometimes develop Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (perihepatitis), presenting with pain in the right upper abdomen or lower right chest, resembling symptoms of cholecystitis or right-sided pleuritis. Both gonococcal and prickly-ash-like sore (trachoma) chlamydial infections can cause this condition, with the latter being more likely. This syndrome is often misdiagnosed as acute cholecystitis.

When a tubo-ovarian abscess forms, despite aggressive treatment, the patient’s temperature remains high, exhibiting remittent or continuous fever, with a thready and rapid pulse. Peritoneal irritation symptoms become more pronounced, often accompanied by rectal pressure and pain. On gynecological examination, the uterus and adnexa are markedly tender, and a tense, slightly cystic, and painful mass may be palpated on one or both sides of the pelvis. If the abscess is located in the cul-de-sac, vaginal examination may reveal a bulging posterior fornix, which is more evident on rectal examination.

If the tubo-ovarian abscess ruptures into the abdominal cavity, the patient suddenly experiences intense and worsening pain, along with nausea, vomiting, and shivering, followed by pallor. Blood pressure drops, the pulse becomes faint and rapid, and cold sweating occurs, indicating clinical shock. Abdominal examination reveals diffuse tenderness, marked rebound tenderness, and muscle rigidity. Abdominal breathing ceases, and symptoms such as abdominal distension and fullness and intestinal paralysis may occur, requiring emergency intervention. If the abscess ruptures into the rectum or posterior vaginal fornix, large amounts of pus may be discharged through the anus or vagina, leading to significant clinical improvement.

Acute salpingo-oophoritis often has certain disease causes, such as hygiene during menstruation and sexual activity, so medical history is very important. Many misdiagnoses often result from neglecting to carefully inquire about the medical history.

The differential leukocyte count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are somewhat helpful for diagnosis. A total leukocyte count of 20–25×109/L, with neutrophils above 0.8–0.85 and toxic granules, suggests the presence of an abscess. If the total leukocyte count is 10–15×109/L, there may not yet be an abscess, and the test should be repeated several times, as a single examination is sometimes not accurate enough. An ESR exceeding 20–30mm/h also often provides clues to abscess formation. However, it is still advisable to combine these findings with clinical manifestations and local examinations for comprehensive analysis and judgment. Certain reproductive organ membranes, such as the fallopian tube and cervical canal membranes, can produce an amylase distinct from that produced by the pancreas. This reproductive amylase is difficult to distinguish from salivary amylase. It has now been discovered that ascites in the rectouterine pouch contains this non-pancreatic amylase, including reproductive and salivary amylase, collectively referred to as isoenzyme amylase, with a normal value of 300μ/L. When the fallopian tube membrane is damaged by inflammation, the level of isoenzyme amylase in the ascites decreases significantly, with the degree of reduction proportional to the severity of the inflammation, potentially dropping to around 40μ/L. However, the patient's serum isoenzyme amylase level remains around 140μ/L. Therefore, for suspected cases of acute salpingitis, a small amount of ascites can be collected via posterior vaginal fornix puncture to measure the isoenzyme amylase level, while simultaneously collecting the patient's blood for enzyme level testing. A ratio of ascites isoenzyme amylase to serum isoenzyme amylase of less than 1.5 is highly indicative of acute salpingitis, as confirmed by surgery in most cases. This test has been recognized as a relatively reliable auxiliary diagnostic method for acute salpingitis.

During the gynecological examination, it is best to collect uterine cavity discharge for bacterial culture and drug sensitivity testing to guide antibiotic use.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

(1) General Support and Symptomatic Treatment: Absolute bed rest in a semi-recumbent position to facilitate drainage and help localize inflammation. Increase fluid intake and consume a high-calorie, easily digestible semi-liquid diet. For those with high fever, administer fluids to prevent dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Correct constipation by administering Chinese medicinals such as Senna Leaf or using enemas with normal saline or a 1, 2, 3 solution. Sedatives and analgesics may be given to patients experiencing pain and restlessness. For severe acute-phase peritoneal irritation symptoms, apply an ice pack or hot water bag to the painful area (cold or hot compress based on patient comfort). After 6–7 days, if gynecological examination and tests (total white blood cell count, ESR) confirm stabilization, switch to infrared or shortwave diathermy (see chronic salpingo-oophoritis for details).

(2) Infection Control: Select appropriate antibiotics based on smear examination or bacterial culture and drug sensitivity results of uterine cavity discharge. Since this type of inflammation is often a mixed infection, and in China, the predominant pathogens are *Escherichia coli* and *Bacteroides*, especially *Bacteroides fragilis*, while gonococcal or chlamydial infections are relatively rare, gentamicin 80,000 U intramuscularly 2–3 times daily or 240,000 U intravenously, along with metronidazole 0.4 g orally three times daily, may be used. Gentamicin is highly effective against *E. coli*, while metronidazole is particularly effective against anaerobic bacteria, with low toxicity, strong bactericidal activity, and affordability, making it widely used. For severe cases, administer broad-spectrum antibiotics intravenously, such as cephalosporins, amikacin, or chloramphenicol. Treatment must be thorough, with appropriate antibiotic dosage and duration. Insufficient dosage may lead to drug-resistant strains and persistent lesions, progressing to chronic disease. Signs of effective treatment include gradual improvement in symptoms and signs, usually observable within 48–72 hours, so avoid switching antibiotics prematurely.

For severe infections, in addition to antibiotics, corticosteroids are often used. Corticosteroids reduce interstitial inflammatory reactions, increase antibiotic concentration at the lesion site, enhance antibacterial effects, and have antipyretic and antitoxic properties, leading to rapid fever reduction and faster absorption of inflammatory lesions—especially beneficial for cases with poor antibiotic response. Administer dexamethasone 5–10 mg intravenously in 500 ml of 5% glucose solution once daily. Once the condition stabilizes slightly, switch to oral prednisone 30–60 mg daily, tapering gradually to 10 mg daily for one week. After discontinuing corticosteroids, continue antibiotics for another 4–5 days.

(3) Local Abscess Puncture and Antibiotic Injection: After abscess formation, systemic antibiotic use may be insufficiently effective. If a tubo-ovarian abscess is close to the posterior fornix and vaginal examination reveals fullness and fluctuation, perform posterior fornix puncture. If pus is confirmed, incise the posterior fornix to drain pus and place a rubber tube for drainage. Alternatively, aspirate the contents first, then inject penicillin 800,000 U plus gentamicin 160,000 U (dissolved in normal saline) through the same puncture needle. If the pus is too viscous to aspirate, dilute it with antibiotic-containing saline until it becomes serosanguineous and easier to aspirate. Typically, the abscess resolves after 2–3 treatments.

(4) If a pelvic abscess ruptures into the abdominal cavity, systemic deterioration often occurs. Immediate measures include fluid and blood transfusion, electrolyte correction, and shock management, including intravenous antibiotics and dexamethasone. While stabilizing the patient, perform exploratory laparotomy as soon as possible to remove pus and excise the abscess if feasible. After surgery, place silicone drainage tubes in both lower abdominal quadrants. Postoperatively, use gastrointestinal decompression and intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, continue correcting dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, and administer blood transfusions to enhance resistance. {|104|}

Prompt diagnosis and proper treatment of acute salpingo-oophoritis generally lead to a favorable prognosis. Mild, simple salpingitis often responds to treatment within 2–3 days, with fever subsiding, tubal edema disappearing in about a week, and thickened fallopian tubes fully resolving within 1–2 months. The tubal folds and ciliated epithelium can return to normal without affecting fertility. Other types of salpingitis are rarely fully resolved, often leaving varying degrees of tubal inflammation and peritoneal adhesions. Narrowing and tortuosity of the tubal wall, luminal obstruction, fimbrial adhesions, and functional impairment can lead to infertility. However, interstitial salpingitis causes milder peritoneal damage; although the tubal wall may be severely affected, the lumen may eventually reopen over time. Yet, with damaged folds and cilia, partial luminal narrowing may slow the transport of fertilized eggs due to poor peristalsis, increasing the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Some cases may progress to chronic disease (see chronic salpingo-oophoritis for details).

Acute salpingo-oophoritis presents clinically as an acute abdomen and should be differentiated from acute appendicitis, ruptured tubal pregnancy, torsion of ovarian cyst pedicle, and acute pyelonephritis, as shown in Table 21-1.

Table 21-1 Differential Diagnosis of Acute Salpingitis

| Acute Salpingitis | Ruptured Tubal Pregnancy, Late Abortion | Torsion of Ovarian Cyst Pedicle | Acute Appendicitis | |

| History | Gradual onset, often occurs after menstruation, childbirth, or late abortion, no history of amenorrhea | Sudden onset, may recur, often with a short history of amenorrhea (e.g., around 40 days). May have nausea, vomiting, and other early pregnancy symptoms | Very sudden onset, no history of amenorrhea, may have a history of lower abdominal mass | Relatively acute onset, no history of amenorrhea |

| Vaginal Bleeding | May have menstrual irregularities, heavy or prolonged periods | Often accompanied by slight spotting vaginal bleeding | Generally no vaginal bleeding | No vaginal bleeding |

| Main Symptoms | Initial fever, increasing burning pain in both lower quadrants. Nausea and vomiting are less common | Sudden severe cramping pain in one lower quadrant, often followed by shock, generalized abdominal pain, and reluctance to move | Sudden colicky pain in one lower quadrant, nausea, vomiting, may feel enlargement of a pre-existing mass | Initial generalized abdominal pain or periumbilical pain, later localized to the right lower quadrant after hours or longer. Often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, dry mouth, fetid breath, and thick yellow tongue coating |

| Main Signs | Fever 39–40°C, flushed face, nervousness, tenderness in both lower quadrants near the suprapubic region | Few cases have fever, pale face, weakness, generalized abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, shifting dullness, severe tenderness in one lower quadrant | Generally no fever, distressed appearance. A moderately sized mass may be palpable in the lower abdomen, usually cystic with marked tenderness | Generally fever does not exceed 38°C, acute illness appearance, McBurney's point tenderness, rebound tenderness, abdominal muscle rigidity |

| Gynecological Examination | Leucorrhea is purulent or bloody, with cervical tenderness, posterior fornix tenderness, and significant bilateral fallopian tube tenderness, possibly with thickening or masses. | There is a small amount of dark purple blood in the vagina, with cervical tenderness, a full posterior fornix, and a floating sensation of the uterus. One side of the adnexa may be normal, while the other side may present a palpable, elastic, and tender solid mass. | The vagina is clean, with a cystic mass palpable in one adnexal region—smooth surface, mobile, and extremely tender. The ipsilateral uterine angle is tender, while the contralateral side is normal (─). | Gynecological examination reveals no abnormalities in the reproductive organs. On rectal examination, there is resistance and tenderness in the right upper intestinal area. |

| Laboratory tests and special examinations | Elevated white blood cell count and neutrophil count, pregnancy test (─), culdocentesis reveals exudate or pus. | Some cases show elevated white blood cell count, but generally normal. Hemoglobin and red blood cell count are decreased. Pregnancy test may be positive, and culdocentesis yields non-clotting dark red blood. B-ultrasound aids in diagnosis. | White blood cell count may be elevated or normal. B-ultrasound aids in diagnosis. | Both white blood cell count and neutrophil count are elevated. |

(1) Differentiation from acute appendicitis: Severe right-sided salpingo-oophoritis can easily be confused with acute appendicitis. However, in acute appendicitis, abdominal pain begins around the umbilicus and localizes to McBurney's point within hours or slightly longer, whereas in acute salpingo-oophoritis, pain is localized to both lower abdominal quadrants from the onset. Acute appendicitis often presents with nausea and vomiting, which may or may not occur in salpingo-oophoritis. Acute appendicitis typically shows only grade I fever but a more pronounced elevation in white blood cell count. On examination, tenderness in appendicitis is at McBurney's point, whereas in salpingitis, tenderness is lower and bilateral. Differentiation becomes difficult when appendicitis perforates and causes peritonitis, as abdominal pain, tenderness, and muscle rigidity then involve the entire lower abdomen, closely resembling salpingo-oophoritis. Pelvic examination may reveal tenderness and resistance, but the severity is less than in acute salpingo-oophoritis, where an enlarged adnexa or adnexal abscess may sometimes be palpated. However, if appendicitis involves the ipsilateral uterine adnexa or forms a pelvic abscess after perforation, differentiation becomes challenging, necessitating exploratory laparotomy.

(2) Differentiation from acute pyelonephritis: Although the kidneys are located above the pelvis, severe acute pyelonephritis can sometimes mimic acute adnexitis. Pain in pyelonephritis is mainly in the upper abdomen but may spread throughout the abdomen, with significant tenderness and percussion pain in the costovertebral angle. High fever may occur, but the patient’s distress is less severe than in adnexitis or appendicitis. Urine (midstream or catheterized sample) examination reveals pus cells and red blood cells.

(3) Differentiation from tubal pregnancy with late abortion or rupture and ovarian cyst torsion: In addition to Table 21-1, refer to relevant chapters for details. If differentiation is difficult, manage as inflammation initially and monitor closely. Exploratory laparotomy may be performed if clinically indicated.