| disease | Abnormal Termination of Coronary Artery |

| alias | Coronary Artery Fistula |

Coronary artery fistulas involve the direct connection of the main or branch vessels of the left or right coronary artery to the cardiac chambers, coronary sinus, pulmonary artery, pulmonary veins, superior vena cava, or bronchial vessels. In 1865, Krause first described this congenital anomaly of coronary artery termination. Trevor reported autopsy findings of a right coronary artery draining into the right ventricle in 1912. By 1971, Oldham et al. had collected 200 cases of coronary artery fistulas from the literature, with the most common being right coronary artery-right ventricular fistulas, accounting for about 25%, while coronary artery connections to the left cardiac chambers were the rarest. With the widespread use of coronary angiography, the number of reported cases of coronary artery fistulas has increased significantly. In a few cases, multiple coronary arteries may be involved. Most coronary artery fistulas occur in isolation, but approximately 25% of cases may coexist with congenital or acquired heart diseases such as septal defects or valvular disorders.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

Coronary artery fistula most frequently involves the right coronary artery or its branches, accounting for approximately 50–55%; involvement of the left coronary artery or its branches occurs in about 35%; and simultaneous involvement of both the left and right coronary arteries or their branches is seen in 5% of cases. In 90% of cases, the coronary artery fistula drains into the right-sided cardiac chambers, pulmonary vessels, or superior vena cava, with the right ventricle being the most common site (40%), followed by the right atrium (25%) and the pulmonary artery (15–20%).

The affected coronary artery becomes dilated, tortuous, elongated, and thin-walled, resembling a vein. In cases with a large fistula and significant shunt flow, the vascular pathology is more severe. The dilated vessels generally exhibit uniform external diameters, but sometimes, near the fistula opening, they may show aneurysmal dilation. However, vascular rupture and atherosclerotic lesions are rare.Coronary artery fistulas typically have a single opening, measuring about 2–5 mm in diameter, with fibrous tissue at the edges. Occasionally, multiple openings may form a sponge-like vascular plexus. The cardiac chambers receiving the coronary artery fistula, particularly the right atrium, left atrium, or coronary sinus, often exhibit marked dilation. In contrast, the left ventricle, right ventricle, and pulmonary artery show little dilation or hypertrophy until congestive heart failure develops.

In coronary artery fistulas draining into the right-sided cardiac chambers, pulmonary artery, or systemic venous system, blood rapidly shunts from the aorta into the right-sided circulation during both diastole and systole. The volume of shunt flow depends on the pressure gradient between the aorta and the receiving cardiac chamber, as well as the size of the fistula. Generally, the left-to-right shunt is small, with the pulmonary-to-systemic blood flow ratio rarely exceeding 1.8. When the coronary artery fistula drains into the left ventricle, shunting occurs only during diastole, and the shunt volume is even smaller. The increased coronary blood flow due to the shunt adds to the cardiac workload, while the fistula may also cause a "steal" effect, reducing distal coronary blood flow and local myocardial perfusion. Coronary artery fistulas draining into the right-sided chambers can lead to increased pulmonary blood flow and elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Those draining into the left ventricle increase left ventricular workload and cause left ventricular hypertrophy. Over time, as the fistula enlarges, shunt flow increases, and cardiac workload rises, congestive heart failure may develop.

Approximately 5–10% of coronary artery fistula cases may be complicated by bacterial endocarditis.bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The vast majority of patients do not present clinical symptoms and are often diagnosed due to the detection of a continuous heart murmur, grade I cardiac enlargement, or pulmonary congestion during physical examinations. Alternatively, they may be incidentally discovered during selective coronary {|###|} angiography. Cases with small coronary {|###|} fistula openings may remain asymptomatic for life. In adult cases with larger fistula openings and significant left-to-right shunting, symptoms such as lack of strength, palpitation, and shortness of breath may occur. Cardiac {|###|} colicky pain and myocardial infarction are very rare, with the former seen in only 7% of cases and the latter in only 3%. Symptoms of congestive heart failure appear in 12–15% of cases, mostly in adult patients, with approximately 20% occurring in those over 20 years old and only 6% in those under 20. The primary disease cause leading to congestive heart failure is long-term left-to-right shunting, though a small number of patients with extremely high shunt volumes may present with congestive heart failure during infancy. When complicated by bacterial endocardial {|###|} inflammation, clinical symptoms such as shiver and fever may appear.

Physical examination: The main sign of a coronary {|###|} fistula is a continuous murmur audible over the precordium. In cases where the fistula connects to the right atrium, the murmur is located at the right sternal border in the second or third intercostal space. If the fistula connects to the right ventricle, the murmur is heard at the lower left sternal border. For fistulas entering the pulmonary {|###|}, the murmur location resembles that of a patent {|###|} ductus arteriosus. If the fistula connects to the left ventricle, only a diastolic murmur is audible at the lower left sternal border. In cases where the fistula opening is close to the anterior chest wall, a systolic tremor may be palpable over the murmur area. Widened pulse pressure is relatively uncommon.

bubble_chart Auxiliary ExaminationChest X-ray: Most cases show no abnormal signs or reveal grade I cardiac enlargement, pulmonary artery prominence, and pulmonary vascular congestion. In cases with congestive heart failure, significant cardiac enlargement and enlargement of the right or left atrium are observed. Sometimes, the cardiac border is obscured by enlarged and tortuous coronary arteries, resulting in an irregularly deformed cardiac silhouette on X-ray films.

Electrocardiogram (ECG): Approximately half of the cases show a normal ECG, while the rest may exhibit signs of right or left ventricular overload.

Cardiac catheterization: In cases where the coronary artery fistula drains into the right heart chambers, increased blood oxygen levels can be detected at the level of the right atrium, right ventricle, or pulmonary artery, thereby identifying the site of the left-to-right shunt. In cases with a large shunt, pulmonary artery pressure may be grade I elevated.

Echocardiography: Cross-sectional echocardiography can reveal significantly enlarged coronary arteries and enlarged cardiac chambers. Pulsed Doppler ultrasound may identify the site of the coronary artery fistula.

Cardiac angiography: Retrograde ascending aortography or selective coronary angiography can demonstrate the passage of contrast medium through the enlarged and tortuous, sometimes aneurysmal, diseased coronary artery into the cardiac chamber, confirming the diagnosis and localizing the site of the coronary artery fistula.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The only treatment for coronary artery fistula is surgical intervention to close the abnormal passage between the coronary artery and the cardiac chamber. In 1947, Biorck and Crafoord first successfully performed a ligation procedure to treat a case of coronary artery-pulmonary artery fistula. In 1959, Xwan et al. performed coronary artery fistula closure under extracorporeal circulation.

Patients presenting with clinical symptoms such as increased ventricular filling load, congestive heart failure, myocardial ischemia, and bacterial endocarditis should be considered for surgical treatment once the diagnosis is confirmed. For infants or young children with small coronary artery fistulas, minimal shunt flow, a pulmonary-to-systemic blood flow ratio of less than 1.3, and no clinical symptoms, opinions on surgical indications remain inconsistent. Some authors suggest long-term follow-up observation, with surgical intervention considered only if the coronary artery fistula enlarges or symptoms appear. Another viewpoint is that spontaneous closure of coronary artery fistulas is highly unlikely, and surgical treatment is relatively simple, safe, and effective. To prevent potential complications in adulthood, surgical treatment should be performed during childhood once the diagnosis is confirmed.

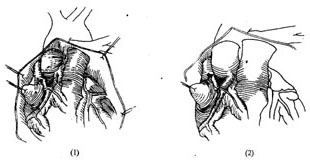

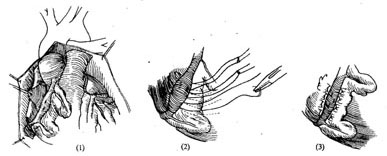

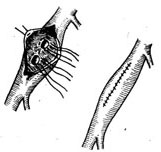

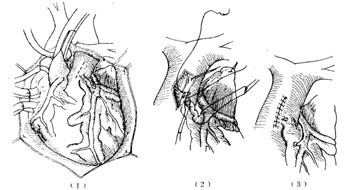

The surgical approach can be selected based on the condition: ① Coronary artery ligation (Figure 1); ② Tangential suture closure of the coronary artery fistula (Figure 2); ③ Coronary artery incision and fistula closure (Figure 3); ④ Transcardiac fistula closure (Figure 4). The first two methods do not require extracorporeal circulation, while the latter two must be performed under extracorporeal circulation (Figure 1) (Figure 2) (Figure 3) (Figure 4). **Operative Technique:** The patient is placed in a supine position, and a midline anterior thoracotomy is performed. The sternum is split longitudinally, and the pericardium is incised. The affected coronary artery appears as a tortuous, dilated vessel on the myocardial surface, making it easily identifiable. A thrill can often be palpated at the fistula site. For fistulas located on the anterior wall of the heart, with the fistula opening at the terminal end of the main coronary artery or its branches, coronary artery ligation can be performed. After isolating the coronary artery near the fistula, temporary occlusion is applied until the thrill disappears completely. The electrocardiogram is closely monitored for 5–10 minutes. If no signs of myocardial ischemia are observed, the artery can be doubly ligated or transected. For fistulas with multiple openings along the inferior wall of the main coronary artery, tangential suture closure is preferred: shallow sutures are placed through the myocardium beneath the affected coronary artery in a perpendicular, interlocking mattress pattern. The sutures are temporarily tightened until the thrill disappears, and if no myocardial ischemia is detected on ECG monitoring, the sutures are tied sequentially to close the fistula. For fistulas located in the left atrioventricular groove involving the circumflex branch or distal segment of the right coronary artery, exposure may be difficult or the artery may exhibit aneurysmal dilation, necessitating partial resection. If the fistula is not at the terminal end of the coronary artery, intracoronary fistula closure under extracorporeal circulation is required. Before initiating extracorporeal circulation, sutures should be placed on the myocardial surface to precisely mark the fistula site, as the thrill may disappear after extracorporeal circulation begins, making localization difficult. After establishing extracorporeal circulation with hypothermia, the ascending aorta is clamped, and the affected coronary artery is incised longitudinally. The fistula is sutured closed, and the coronary artery incision is then repaired. If the coronary artery exhibits aneurysmal dilation, partial resection of the aneurysm wall may be performed before suturing. In rare cases, the aneurysm may need to be excised and replaced with a segment of the saphenous vein. For coronary artery fistulas draining into the atrium, ventricle, or pulmonary artery, extracorporeal circulation with mild hypothermia is used. The ascending aorta is clamped, and the chamber or vessel receiving the fistula is incised to allow intracavitary fistula closure.

**Figure 1:** Coronary artery ligation for right coronary artery-superior vena cava fistula.

**Figure 2:** Tangential suture closure of coronary artery fistula.

Figure 3 Coronary stirred pulse fistula ligation and closure

Figure 4 Transpulmonary stirred pulse incision closure and coronary stirred pulse fistula resection

The surgical treatment of coronary stirred pulse fistula yields favorable outcomes, though the risk increases in cases complicated by giant coronary stirred pulse stirred pulse aneurysms, with a surgical mortality rate of approximately 2%. The postoperative myocardial infarction complication rate ranges from 3% to 6%. Recurrence of coronary stirred pulse fistula occurs in about 4% of patients postoperatively. Long-term follow-up shows disappearance of clinical symptoms and restoration of normal cardiac function.

The natural course of coronary artery fistula remains uncertain. Spontaneous closure of coronary artery fistula is extremely rare, as is spontaneous rupture. After presenting at birth or during childhood, small fistulas may persist without enlargement; moderately sized fistulas may gradually enlarge, but progress slowly, often taking over 15 years; large fistulas may manifest with dyspnea, congestive heart failure, and cardiac colicky pain during infancy or adolescence. Since most fistulas are generally small, clinical symptoms of prolonged increased left ventricular filling volume typically appear after the age of 50. Approximately 5–10% of patients may develop bacterial endocarditis, which can occur at any age.

The continuous murmur produced by coronary artery fistula is similar to and easily confused with patent ductus arteriosus, aortopulmonary septal defect, rupture of aortic sinus aneurysm, high ventricular septal defect with aortic regurgitation, and arteriovenous fistula of the chest wall or lung. For cases where the timing, location, loudness, nature, conduction direction of the murmur, and clinical symptoms are atypical, the possibility of coronary artery fistula should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Cardiac catheterization, echocardiography, aortography, and selective coronary angiography can confirm the diagnosis.