| disease | Throat Trauma |

| alias | Dashboard Syndrome, Dashboard Syndrome |

Laryngeal trauma can be classified into two main categories: closed injuries and open injuries. Acute laryngeal trauma is prone to causing airway obstruction, which can be life-threatening. Improper management may lead to chronic laryngeal stenosis, voice disorders, or difficulties in extubation. Therefore, acute laryngeal trauma requires early diagnosis and treatment by specialists to prevent or reduce complications.

bubble_chart Pathogenesis

Closed injuries include laryngeal contusion, cartilage fracture, and dislocation. The leading cause is traffic accidents, where general car crashes often result in multiple injuries, with laryngeal trauma being one of them. The steering wheel, dashboard, and seat backrest of a car can easily directly impact the larynx, and this type of injury is referred to as dashboard syndrome. The second most common cause is sports competitions (such as boxing, ball impacts, etc.), followed by workplace accidents. Other causes include iatrogenic injuries from endoscopy or tracheal intubation.

Open injuries include laryngeal stab wounds, incised wounds, and penetrating wounds. The primary causes are gunshot wounds and sharp instrument injuries, with the former being more common during wartime and the latter more prevalent in peacetime.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Laryngeal contusion can easily lead to submucosal edema, hematoma, mucosal tearing, cartilage fracture, and dislocation. Common symptoms include respiratory obstruction causing dyspnea and laryngeal stridor; voice changes or aphonia; cough, hemoptysis, neck pain, and odynophagia. Laryngeal cartilage dislocation includes two types: cricothyroid joint dislocation and cricoarytenoid joint dislocation. In the former, the inferior horn of the thyroid cartilage is often located posterior to the cricothyroid joint surface, with neck pain on the affected side possibly radiating to the ear. The recurrent laryngeal nerve passing through the cricothyroid joint is often injured, leading to aphonia. Some patients may experience voice changes even without recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. The latter presents with hoarseness, localized pain, dysphagia, or even dyspnea. Examination may reveal swelling of the arytenoid region and aryepiglottic fold, with the vocal cords obscured. After swelling subsides, the arytenoid cartilage may be displaced anteromedially, the vocal cords appear slack and curved, and the glottis fails to close tightly during phonation.

After laryngeal cartilage fracture, subcutaneous emphysema of the neck is common, along with respiratory obstruction. Palpation may reveal fracture signs such as the disappearance of the thyroid cartilage prominence or the arch of the cricoid cartilage, and mucosal tearing within the laryngeal cavity.Laryngeal incisions are mostly self-inflicted. Clinically, most cases involve suicidal attempts, with half being stab wounds. Incisions made with sharp blades are usually transverse. Based on comprehensive statistics from domestic and international reports, the most common site is the thyroid cartilage (33.0%), followed by the thyrohyoid membrane (31.1%), cricothyroid membrane (12.1%), cricoid cartilage (9.8%), trachea (8.0%), and above the hyoid bone (5.7%). Symptoms include hoarseness, aphonia, dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis. Complications may include wound infection, chondromembraneitis, difficulty in extubation, secondary bleeding, subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, mediastinal emphysema, vocal cord paralysis, tracheoesophageal fistula, pneumonia, and mediastinitis.

The symptoms and signs of penetrating laryngeal injuries vary depending on the type of weapon, bullet velocity, and injury site. The most prominent early symptom is bleeding. Even if major neck vessels are not injured, death may occur due to blood aspiration causing asphyxia or excessive blood loss leading to shock. Subsequently, tissue edema, hematoma, and vascular injury-induced dyspnea may develop, along with subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, dysphagia, and voice disorders.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

I. Emergency Measures

1. Hemostasis

The emergency treatment for major neck hemorrhage involves inserting fingers into the bleeding wound to directly compress the damaged blood vessel or pressing the carotid pulse area to control bleeding. Then, identify the bleeding point, use vascular forceps to stop the bleeding, and ligate. Most patients arriving at the hospital have already stopped bleeding and are in a state of shock. All bleeding points and clotted vascular stumps should be identified and ligated to prevent secondary hemorrhage. For excessive blood loss, immediate blood transfusion, fluid infusion, cardiac stimulation, blood pressure elevation, and shock prevention are necessary. Additionally, aspirate blood that has entered the trachea to prevent aspiration pneumonia or atelectasis.

In critical situations, a tracheal cannula or rubber tube can be inserted into the trachea through the original wound to aspirate secretions and misaspirated blood, temporarily maintaining airway patency. Once the condition stabilizes, a low tracheotomy should be performed. Prophylactic tracheotomy is generally required for lacerations penetrating into the pharynx and tracheal lumen.

3. Nasogastric Feeding

This reduces swallowing movements and the risk of aspiration, allowing the injured larynx to rest.

II. Wound Management

1. Debridement

Rinse the wound with saline and use gauze to block the wound leading to the pharyngeal cavity. Remove blood clots, sputum, and foreign bodies, and trim nonviable tissue, but avoid arbitrarily cutting the laryngeal mucosa. Re-ligate any oozing bleeding points.

2. Wound Suturing

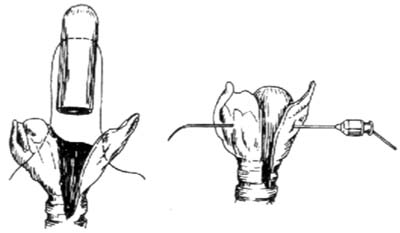

For mucosal wounds, use fine catgut sutures to carefully close the wound, leaving no exposed areas to prevent granulation tissue growth and postoperative oozing. To avoid disruption of wound edge healing due to coughing or laryngeal movement, mattress sutures are preferable. If there is significant mucosal loss, mucosal flaps or free mucosal grafts should be used. Preserve cartilage as much as possible, except for small fragments that are mostly detached or nonviable. Cartilage itself does not necessarily require suturing. If the cartilage membrane cannot be sutured, use wire to fix the cartilage edges, and if necessary, support the laryngeal lumen with a laryngeal stent (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Laryngeal Stent Fixation (Illustration of Wire Penetration)

3. Joint Reduction

After the swelling from laryngeal contusion subsides, if there is cricoarytenoid joint dislocation, early reduction is advisable, preferably within 1–3 weeks. The reduction method: Under topical anesthesia of the larynx, use laryngeal forceps to manipulate the cricoarytenoid joint. The direction of manipulation depends on the dislocation, with the goal of improving vocalization post-reduction.

1. Generally, adopt a supine position with the head slightly elevated and stabilized with sandbags to prevent lateral head and neck movement.

2. Within 3 days post-injury, administer tetanus antitoxin (1500–3000 IU) and sufficient antibiotics to prevent local and pulmonary infections.

3. For acute laryngeal trauma with a laryngeal stent, the stent can usually be removed after 2 weeks.

4. The timing of tracheal cannula removal should be determined case by case, but generally, it is advisable to observe for 1–3 months before removal.