| disease | Raynaud's Disease |

| alias | Raynaud's Syndrome, Raynaud's Syndrome |

Raynaud's syndrome refers to episodic spasms of the peripheral arteries. It is often triggered by factors such as cold stimulation or emotional stress, manifesting as intermittent changes in skin color of the extremities—pallor, cyanosis, and flushing. The upper limbs are usually more affected, though it occasionally occurs in the lower limbs.

bubble_chart Etiology

The disease cause of Raynaud's syndrome is still not entirely clear. Cold stimulation, emotional hormones, or mental stress are the primary triggering factors. Other contributing factors include infections, fatigue, etc. Since the condition often worsens during menstruation and improves during pregnancy, some believe it may be related to gonadal function.

Recent advances in immunology indicate that the vast majority of Raynaud's syndrome patients exhibit numerous abnormalities in serum immunity, with antibodies exceeding the composition of homologous nuclei. Antigen-antibody immune complexes may exist in the patient's serum, acting through chemical transmitters or directly on sympathetic nerve terminals, leading to vasospastic changes. Clinically, after using drugs that block sympathetic nerve terminals, Raynaud's symptoms can be completely alleviated.

Pallor, cyanosis, and flushing are the three stages of skin color changes in Raynaud's syndrome. Pallor is caused by spasms in the small stirred pulse and venules at the extremities, resulting in slowed capillary perfusion and reduced or absent blood flow in the skin vessels. After a few minutes, due to hypoxia and metabolic products abdominal mass, the capillaries—and possibly the venules—dilate slightly, allowing a small amount of blood to flow into the capillaries. Rapid deoxygenation then leads to cyanosis. Cyanosis occurs when the stirred pulse spasm has subsided but venous spasm persists. When the vascular spasm in the extremities resolves, a large amount of blood enters the dilated capillaries, causing reactive hyperemia, and the skin turns flushed. Once normal blood flow through the small stirred pulse is restored and capillary perfusion returns to normal, the episode stops, and the skin color returns to normal.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsRaynaud's syndrome is not uncommon in clinical practice. It is more prevalent in women, with a male-to-female incidence ratio of approximately 1:10. The onset age is mostly between 20 and 30 years old, rarely exceeding 40. It is most commonly seen in cold regions and occurs frequently during cold seasons.

Patients often experience sudden pallor of the fingers after exposure to cold or emotional stress, followed by cyanosis. The episode typically starts at the fingertips and then spreads to the entire finger or even the palm. It is accompanied by local coldness, numbness, a pins-and-needles sensation, and reduced sensitivity. After several minutes, the skin gradually turns flushed and warm, accompanied by a burning, distending sensation before finally returning to its normal color. Drinking warm beverages or alcohol, or warming the affected limb, often alleviates the episode. Generally, after removing the cold stimulus, the time for the skin color to transition from pallor, cyanosis, and flushing back to normal is about 15–30 minutes. A few patients may initially present with cyanosis without a pallor stage or transition directly from pallor to flushing without cyanosis. During episodes, the radial pulse does not weaken. Between episodes, aside from slightly cold fingers and mild pallor, there are no other symptoms.

The condition usually affects the fingers but may also involve the toes, and occasionally the ears and nose. Symmetrical symptom presentation is an important characteristic of Raynaud's syndrome. For example, the little and ring fingers on both sides are often the first to be affected, followed by the index and middle fingers. The thumbs, due to their richer blood supply, are rarely involved. The degree and extent of skin color changes are also identical on both hands. A few patients may initially experience unilateral symptoms before progressing to bilateral involvement.

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

(1) Laboratory Tests Tests indicating systemic connective tissue diseases, such as antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, immunoglobulin electrophoresis, complement levels, anti-native DNA antibodies, cryoglobulins, and the Coombs test, should be performed as routine examinations.

(2) Special Examinations

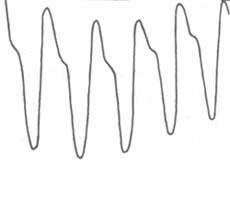

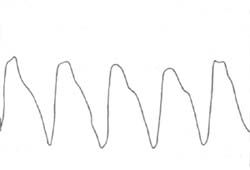

1. Cold Stimulation Test After the fingers are cooled by exposure to cold, photoplethysmography (PPG) is used to record the time required for finger circulation to return to normal, serving as a simple, reliable, and non-invasive method to assess fingertip circulation. During the test, the patient should sit quietly indoors (room temperature 26±2°C) for 30 minutes. After recording the fingertip circulation waveform with PPG, both hands are immersed in ice water for 1 minute, then immediately dried. The finger circulation is recorded every minute for 5 minutes. In normal individuals, fingertip circulation returns to baseline within 0–2 minutes, whereas in patients with Raynaud’s syndrome, the time required for fingertip circulation to return to normal is significantly prolonged (exceeding 5 minutes). In normal individuals, the plethysmographic wave is biphasic, with a main peak wave and a dicrotic wave. In patients with Raynaud’s syndrome, the plethysmographic wave is monophasic, with a low, blunt, and flat peak or even absent (Figures 1–2). This test can also be used to evaluate treatment efficacy. If symptoms improve after medication, the fingertip circulation recovery time will shorten.

Figure 1: Plethysmographic wave of a normal individual’s fingertip

Figure 2: Plethysmographic wave of a Raynaud’s disease patient’s fingertip

2. Finger Temperature Recovery Time Measurement After the fingers are cooled, a thermistor probe is used to measure the time required for the temperature to return to normal, providing an objective basis for diagnosing Raynaud’s phenomenon by estimating finger blood flow. In 95% of normal individuals, finger temperature returns to baseline within 15 minutes, whereas in the majority of Raynaud’s syndrome patients, the time required for finger temperature to return to normal exceeds 20 minutes. This test can also be used to assess treatment efficacy.

3. Finger Plethysmography If necessary, upper limb plethysmography can be performed to evaluate finger blood flow, aiding in the diagnosis of Raynaud’s syndrome. It can also reveal whether there are organic vascular changes. Plethysmography is not only invasive but also relatively complex, so it should not be used as a routine examination.

In special examinations, measuring upper limb nerve conduction velocity can help detect possible carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand X-rays are useful for identifying rheumatoid arthritis and finger calcification.

The vast majority of patients with Raynaud's syndrome can be diagnosed based on a history of intermittent changes in the color of the skin on their extremities. However, it is best to observe the condition during symptom episodes, noting the nature, extent, severity, and duration of the skin color changes. Immersing the patient's hands or feet in cold water or exposing them to cold air can induce these typical symptoms.

To detect potential underlying related diseases as early as possible, the medical history should focus on whether there is a history of systemic connective tissue diseases and vascular disorders such as arteriosclerosis or vasculitis, a history of vascular trauma, a history of medication with ergotamine, β-blockers, or contraceptive drugs, and a history of long-term occupational use of vibrating tools.

The physical examination should focus on identifying signs suggestive of systemic connective tissue diseases, such as thinning or tightening of the skin, telangiectasia, rashes, or dry lips; thickening of the joint synovium, effusion, or other evidence of arthritis. Carefully inspect the skin of the fingers for ulcers or areas of hyperkeratosis from healed ulcers; pay attention to peripheral arterial pulses; and remain vigilant for the presence of carpal tunnel syndrome. Patients in whom no related diseases are found should undergo long-term follow-up.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The most important aspect of treating Raynaud's syndrome should be addressing the underlying disease. Symptomatic treatment for this condition includes drug therapy, biofeedback, and surgery, which are selected based on the patient's specific circumstances.

1. Drug Therapy The following medications are commonly used clinically:

⑴ Priscol (Priscol): Also known as tolazoline, taken orally at 25–50mg per dose, 4–6 times daily, after meals. For severe local pain or ulcer formation, the dose can be increased to 50–100mg per dose. Intramuscular, intravenous, or intra-arterial injection doses are 25–50mg per dose, 2–4 times daily. Some patients may experience side effects such as tidal fever, syncope, dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting, and goosebumps.

⑵ Reserpine (reserpine): Due to its catecholamine-depleting and serotonin-depleting effects, it has been a long-standing and effective medication for treating Raynaud's phenomenon, recommended by many authors. Oral doses vary widely. Kontos reported that an oral dose of 1mg/day for 1–3 years can reduce the frequency and severity of symptom episodes.

In 1967, Abboud et al. first reported the use of intra-arterial injection of reserpine for treating Raynaud's syndrome with satisfactory results. In recent years, many scholars have reported that direct puncture of the brachial artery followed by slow injection of reserpine (0.25–0.5mg dissolved in 2–5ml of saline) can significantly improve symptoms, with effects lasting 10–14 days. Repeat injections are needed every 2–3 weeks. Due to the risk of arterial injury, this method is limited in application, but many scholars believe it is still worth trying for severe cases with acral ulcers.

Intravenous reserpine injection after venous occlusion is a local administration method. The procedure involves placing a tourniquet above the elbow joint, puncturing a distal vein, inflating the tourniquet to maintain a pressure of 33.3kPa (250mmHg), and then slowly injecting 0.5mg of reserpine dissolved in 50ml of saline into the vein, allowing the medication to reflux to the extremities. This method is simpler than intra-arterial injection and has similar therapeutic effects, with results typically lasting 7–14 days.

⑶ Nifedipine (nifedipine): A calcium channel blocker that dilates blood vessels by reducing calcium storage or binding capacity on muscle cell membranes, thereby inhibiting action potential formation and smooth muscle contraction. An oral dose of 20mg three times daily for 2 weeks to 3 months has been shown in clinical studies to significantly improve symptoms in moderate to grade III Raynaud's syndrome.

⑷ Guanethidine (guanethidine): Has effects similar to reserpine. The oral dose is 5–10mg per dose, three times daily. It can also be combined with phenoxybenzamine at a daily dose of 10–30mg, with about 80% of patients responding positively.

⑸ Methyldopa (methyldopa): A daily dose of 1–2g can prevent Raynaud's syndrome episodes in most patients. Blood pressure should be monitored during treatment.

Recently, some experts have reported that the following drugs have also achieved good therapeutic effects in the treatment of Raynaud's phenomenon. ①Prostaglandins: Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and prostacyclin (PGI2) both have the effects of vasodilation and inhibition of platelet aggregation. They show satisfactory efficacy for Raynaud's syndrome with finger infection and gangrene. Intravenous infusion of PGE1 at 10ng/min for 72 hours. Infusion of PGI1 (7.5ng/kg/min for 5 hours) once a week for a total of 3 times. The therapeutic effect generally lasts for 6 weeks. ②Stanozolol: It is an anabolic steroid hormone with the effect of activating plasminogen, and it is reported to dissolve fibrin deposited in the finger stirred pulse and reduce plasma viscosity. Take 5mg orally, twice a day for 3 months.

In addition, local application of 205 nitroglycerin ointment, 4-6 times daily, has been clinically shown to significantly reduce the frequency of Raynaud's phenomenon attacks, with marked alleviation of numbness and pain.

Traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture have certain therapeutic value for this condition, but further clinical research is needed to advance their development.

2. Biofeedback Therapy Biofeedback therapy involves detecting and amplifying biological signals that are normally imperceptible or difficult to perceive, using specialized equipment. These signals are then converted into feedback through a recording and display system, allowing patients to become aware of these functional changes. This enables them to associate certain sensations with bodily functions and, to some extent, regulate these functions. In 1973, Jacobson reported the use of biofeedback therapy to treat 20 cases of Raynaud's phenomenon. The method divided the 20 cases into two groups of 10 each. The first group used a temperature device connected to a light indicator system to measure skin temperature every 15 seconds. When the temperature rose or stabilized, the light would illuminate; when the temperature dropped, the light would remain off. Thus, patients received a visual stimulus reflecting their skin temperature. The second group underwent self-control training. During the sessions, they were guided via audio recordings to take deep breaths, relax, and then recall pleasant, warm experiences—such as basking in warm sunlight, lying on soft sand with gentle waves lapping the shore. Each session lasted one hour. In the first month, sessions were conducted three times weekly; in the second month, twice weekly; and in the third month, once weekly. Patients were also instructed to perform the same training at home for 15 minutes daily. The therapeutic effects were similar in both groups. After treatment, when patients entered a cold room at 3.3°C, their skin temperature remained at 21.4°C (compared to 22.2–23.0°C in healthy individuals), whereas before treatment, it had dropped to an average of 19.5°C. Biofeedback therapy is a new clinical approach developed over the past decade. It is simple, painless, and free of side effects for patients. Literature reports suggest it has certain efficacy and warrants further exploration.

In recent years, some researchers have achieved relatively satisfactory results using plasma exchange therapy and induced vasodilation therapy, though further studies are needed.

3. Surgical Therapy The vast majority (80–90%) of patients with Raynaud's syndrome experience symptom relief or halted progression after medical treatment. Only a small number of patients—those who show no improvement despite adequate drug dosage and duration, whose condition worsens, whose symptoms severely impact work and life, or who exhibit trophic changes in the fingertips—may be considered for sympathectomy. However, preoperative assessment of vasomotor response is essential. If the vasomotor index is insufficient, sympathectomy may not yield the desired results. Reports indicate that only 40–60% of patients experience symptom improvement post-surgery, and the relief is often short-lived, with symptoms recurring within two years. The procedure shows definitive efficacy for patients with associated arterial occlusion disease but poor results for those with connective tissue disorders.

Factors influencing postoperative efficacy:

(1) Cold exposure: A major trigger for this condition, it can affect postoperative outcomes.

(2) Severity of local vascular lesions: Patients without organic arterial disease in the fingertips respond better, whereas those with such conditions show poorer results.

(3) Incomplete sympathectomy or nerve regeneration: Incomplete removal of sympathetic ganglia due to anatomical variations or surgical technique can compromise efficacy. Many scholars believe that nerve tissue can regenerate after sympathectomy, thereby affecting long-term results.

Including avoiding cold stimulation and emotional agitation; abstaining from smoking; avoiding the use of ergotamine, β-receptor blockers, and contraceptives; for those with obvious occupational causes (such as prolonged use of vibrating tools or low-temperature operations), changing jobs if possible. Carefully protect fingers from trauma, as minor injuries can easily lead to fingertip ulcers or other nutritional and sexually transmitted disease changes. Drinking small amounts of alcoholic beverages in daily life can improve symptoms. If conditions permit, relocating to a mild and dry climate can further reduce symptom episodes. Alleviating patients' psychological concerns and maintaining optimism are also important preventive measures.

It is important to differentiate from other vascular dysfunction disorders characterized by changes in skin color.

(1) Acrocyanosis: This is a vasospastic disorder caused by autonomic dysfunction. It is more common in young women, with symmetrical and uniform cyanosis of the hands and feet. Cold can exacerbate the symptoms. It is often accompanied by autonomic dysfunction phenomena such as dermatographism or profuse sweating of the hands and feet. The pathological changes involve persistent spasms of small stirred pulses in the extremities, as well as capillary and venous varicosities, necessitating differentiation from Raynaud's syndrome. Patients with acrocyanosis do not exhibit typical skin color changes; the cyanosis is more extensive, affecting the entire hands and feet, and may even involve the whole limb. The cyanosis persists for a longer duration. Although cold can worsen the symptoms, they often do not immediately alleviate or disappear in a warm environment. Emotional stimuli and mental stress generally do not trigger this condition.

(2) Livedo reticularis: Mostly seen in women, it is caused by spasms of small stirred pulses and atonic dilation of capillaries and veins. The skin shows persistent网状 or spotted cyanosis. The lesions mostly occur in the lower limbs, occasionally affecting the upper limbs, trunk, and face. The affected limbs often experience coldness, numbness, and paresthesia. The livedo becomes more pronounced in cold conditions or when the limbs are dependent. In a warm environment or after elevating the affected limb, the markings减轻 or disappear. Clinically, it can be divided into three types: cutis marmorata, idiopathic网状 purplish macula, and symptomatic livedo reticularis.

(3) Erythromelalgia: The disease cause is still unclear. The pathological changes involve symmetrical, paroxysmal vasodilation of the extremities. It is more common in young women. The onset is sudden, with both feet affected simultaneously, and occasionally the hands may also be involved. It presents as symmetrical, paroxysmal severe burning pain. When the foot temperature exceeds the critical threshold (approximately 33–34°C), such as when the feet are in warm bedding, the pain can发作, often described as burning, but may also be stabbing pain or distending pain. Pain发作 can be triggered by dependent positioning, standing, or movement, and can be alleviated by elevating the affected limb, resting, or exposing the feet outside the bedding. During发作, the feet exhibit erythema and congestion, elevated skin temperature with sweating, and增强 pulsations of the dorsal pedal and posterior tibial stirred pulses. Based on these features, it is easily distinguishable from Raynaud's syndrome. A少数 cases of erythromelalgia may be secondary to polycythemia vera or diabetes.