| disease | Anal Fissure |

| alias | Anal Fissure |

An anal fissure is a small ulcer in the skin layer of the anal canal below the dentate line. It runs parallel to the longitudinal axis of the anal canal, measuring about 0.5 to 1.0 cm in length, and appears spindle-shaped or oval. It often causes severe pain and is difficult to heal. Superficial lacerations on the anal canal surface should not be considered anal fissures, as they typically heal quickly and are often asymptomatic. Anal fissure is a common disorder of the anal canal and a frequent cause of severe pain in the anal region among young and middle-aged adults. Although most prevalent in middle-aged individuals, it can also occur in the elderly and children. Generally, it is slightly more common in men than in women, though some reports indicate a higher incidence in women. An anal fissure usually presents as a single tear, with the vast majority occurring in the posterior midline of the anal canal.

bubble_chart Etiology

The disease causes of anal fissure are related to the following factors:

(1) Anatomical factors

The superficial part of the external anal sphincter forms the anococcygeal ligament at the posterior aspect of the anus, which is relatively rigid and less elastic. Additionally, the posterior aspect of the anus bears greater pressure, making the posterior midline more prone to injury.

(2) Trauma

Patients with chronic constipation often experience dry and hard stools, and excessive straining during defecation can easily injure the anal canal skin. Repeated injuries may deepen the fissure to the full thickness of the skin, forming a chronic infectious ulcer. Some reports indicate that constipation accounts for 14–24% of anal fissure cases, but constipation may also be a consequence of anal fissure due to the patient's fear of defecation. Additionally, postpartum conditions can lead to anal fissures, accounting for approximately 3–9%.

(3) InfectionChronic inflammation near the dentate line, such as posterior midline anal sinusitis, can spread downward, leading to subcutaneous abscesses that rupture and form chronic ulcers.

Acute anal fissures have a shorter onset period, appearing red, with a shallow base, fresh and neat fissures, and no scar formation. Chronic anal fissures have a longer course, recur repeatedly, and feature an irregular, deep base. The upper end often presents with hypertrophic papillae, while the lower end commonly exhibits a sentinel pile, collectively referred to as the "triad of anal fissure." The sentinel pile is caused by lymphatic stasis in the subcutaneous tissue, resembling external hemorrhoids. During examination, the sentinel pile is often noticed before the fissure, aiding diagnosis, hence its name "sentinel pile" or "fissure hemorrhoid." In advanced stages, complications such as perianal abscesses and subcutaneous anal fistulas may also occur.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The typical clinical manifestations of anal fissure patients are pain, constipation, and hematochezia.

(1) Pain

Anal fissure can cause cyclical pain due to defecation, which is the main symptom of anal fissure. During defecation, fecal matter irritates the nerve endings on the ulcer surface, immediately causing a burning pain in the anus. However, the pain subsides a few minutes after defecation, a period known as the pain-free interval. Subsequently, due to spasms of the internal sphincter muscle, severe pain occurs again, which can last from half an hour to several hours, making the patient restless and difficult to endure until the sphincter muscle fatigues and relaxes, relieving the pain. However, pain recurs with the next bowel movement. This clinical pattern is referred to as the anal fissure pain cycle. The pain may also radiate to the perineum, buttocks, inner thighs, or sacrococcygeal region.

(2) ConstipationDue to the pain in the anus, patients may avoid defecation, leading to constipation over time. The stool becomes harder, and constipation can further aggravate the anal fissure, creating a vicious cycle.

(3) Hematochezia

During defecation, small amounts of fresh blood may be seen on the surface of the stool or on toilet paper, or there may be dripping of fresh blood. Massive bleeding is rare.

(4) Others

Such as cutaneous pruritus, secretions, diarrhea, etc.

A history of painful defecation, with typical intermittent pain periods and pain cycles, makes diagnosis straightforward. Local examination revealing the "triad sign" of anal fissure in the posterior midline of the anal canal confirms the diagnosis. However, in the early stages of anal fissure, it must be differentiated from anal skin abrasions. Once anal fissure is confirmed, digital rectal examination and anoscopy are generally not recommended to avoid causing severe pain. For chronic ulcers in lateral positions, rare conditions such as subcutaneous nodules, cancer, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis should be considered, and a pathological biopsy should be performed if necessary.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The principle is to soften the stool, maintain smooth bowel movements, relieve pain, alleviate sphincter muscle spasms, break the vicious cycle, and promote wound healing. Specific measures are as follows:

(1) Maintain smooth bowel movements

Administer oral laxatives or liquid paraffin to soften and lubricate the stool. Increase fiber-rich foods and adjust bowel habits to gradually correct constipation.

(2) Local sitz baths

Use a 1:5000 warm potassium permanganate solution for sitz baths before and after defecation to maintain local cleanliness.

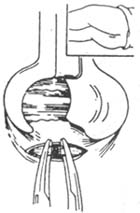

(3) Anal dilationSuitable for acute or chronic anal fissures without concurrent hypertrophic papillae or sentinel piles. The advantages include simplicity, no need for special instruments, rapid efficacy, and requiring only daily sitz baths post-procedure. Method: After local anesthesia, the patient assumes a lateral position. First, use two index fingers to forcefully dilate the anal canal, then gradually insert two middle fingers and maintain dilation for 5 minutes. In males, dilation should be directed anteriorly and posteriorly to avoid contact with the ischial tuberosity, which may hinder dilation. Females, with their wider pelvis, do not face this issue. Anal dilation relieves sphincter spasms, providing immediate pain relief post-procedure. The fissure wound expands and opens, ensuring proper drainage and facilitating rapid healing of superficial wounds. However, complications may include bleeding, perianal abscess, hemorrhoidal prolapse, and temporary fecal incontinence, with a relatively high recurrence rate.

For chronic anal fissures that do not heal with non-surgical treatments, the following surgical interventions may be considered.

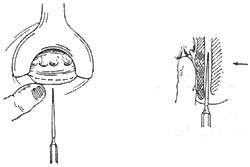

1. Anal fissurectomy This involves excising the anal fissure and the surrounding triangular skin. Under local or spinal anesthesia, a fusiform or fan-shaped incision is made to completely remove the sentinel pile, hypertrophic anal papilla, and anal fissure. If necessary, a vertical partial internal sphincterotomy is performed. The advantage is complete removal of the lesion, creating a wide wound for optimal drainage and granulation tissue growth from the base. The drawback is the larger wound size, leading to slower healing.

2. Internal sphincterotomy The internal sphincter, with its involuntary circular muscle properties, is prone to spasms and contractions, the primary cause of anal fissure pain. Thus, internal sphincterotomy can cure anal fissures. Partial internal sphincterotomy rarely causes fecal incontinence. There are three methods:

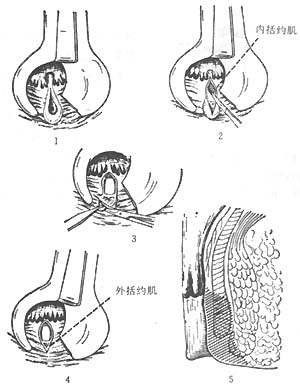

(1) Posterior internal sphincterotomy (Figure 1): In lithotomy or prone position, under local or general anesthesia, use a bivalve speculum or anoscope to expose the posterior midline anal fissure. Directly incise the lower edge of the internal sphincter through the fissure, extending from the anal verge to the dentate line (~1.5 cm). The tissue between the internal and external sphincters should also be separated. Sometimes, the lower part of the external sphincter is incised to improve drainage. Inflamed anal sinuses, hypertrophic papillae, or external hemorrhoids may be excised concurrently. The wound is left open to heal naturally. However, healing is slow, and occasional "keyhole" deformities may impair anal function, making this procedure unsuitable for some patients.

Figure 1: Posterior internal sphincterotomy

(2) Lateral open internal sphincterotomy (Figure 2): After palpating the intersphincteric groove, make a 2 cm curved incision in the skin lateral to the anal verge. Insert a curved hemostat through the incision to reach the intersphincteric groove. After exposing the internal sphincter, clamp its lower edge with two curved hemostats and dissect upward to the dentate line. Under direct vision, excise a portion of the internal sphincter for biopsy confirmation. Ligate both ends for hemostasis and suture the skin with silk thread. Advantages: The procedure is performed under direct vision, ensuring complete muscle division, thorough hemostasis, and the ability to obtain tissue for biopsy.

Figure 2: Lateral internal sphincterotomy

(3) Lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy (Figure 3): After local anesthesia, palpate the intersphincteric groove, insert an ophthalmological scalpel between the internal and external sphincters, and cut the internal sphincter from the outside inward, avoiding penetration of the anal canal skin. Advantages of this method: It avoids an open wound, reduces pain, and promotes faster wound healing. Disadvantages: The muscle may not be completely severed, and bleeding can sometimes occur. Therefore, this procedure is only suitable for experienced doctors. Marti (1994) proposed inserting a B-mode ultrasound rotating probe into the anorectal canal during lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy. Immediately after cutting the muscle, the probe can check whether the internal sphincter has been severed and determine the extent of the cut. This probe eliminates the need for the surgeon's finger to be inserted into the rectum and assists in the surgical procedure. Both of the above methods can simultaneously remove external hemorrhoids and hypertrophied papillae.

Figure 3 Lateral Subcutaneous Internal Sphincterotomy

Note: Left. After local anesthesia, a small knife is inserted between the internal and external sphincters; Right. The internal sphincter is cut from outside inward, with a finger inserted into the rectum for protection.