| disease | Limb Replantation |

In 1963, Chen Zhongwei, Qian Yunqing, and others were the first in the history of world medicine to report a successful replantation of a completely severed limb 2.5 cm above the right wrist. The patient regained good function in the right hand after rehabilitation. Malt and Mckhann also reported in 1964 their successful replantation of a 12-year-old boy's upper arm in May 1962. In 1965, Kleinert achieved successful vascular anastomosis in fingers, and the same year, Harry Buncke conducted successful experimental research on rabbit ear and monkey thumb replantation. In 1967, Chen Zhongwei, Komatsa, Tamai, and others successively reported successful finger replantations. The success of limb replantation demonstrated that, under certain conditions, severed human tissues and organs can have their blood supply reconstructed using microsurgical techniques, allowing them to reintegrate into the body—a significant breakthrough in medical concepts. Nearly 40 years have passed since China's first successful limb replantation in 1963, and the country has consistently maintained world-leading standards in the field of limb (finger) replantation.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

(1) Preoperative Preparation and Anesthesia

1. Correcting Shock In addition to general preparation, the first priority is to correct shock. Limb amputation patients often suffer from shock due to massive blood loss, which must be promptly addressed while actively preparing for surgery. Surgery should only proceed once blood pressure has normalized. Performing replantation without fully correcting shock can endanger the patient’s life. Low blood pressure also increases the risk of vascular anastomosis thrombosis.

2. Anesthesia For the upper arm, continuous brachial plexus anesthesia is preferred, typically using 10 mL of 0.3% dicaine combined with 10 mL of 2% lidocaine, providing approximately 3 hours of anesthesia. Repeat injections may be administered if necessary. Bupivacaine can be used for longer anesthesia duration. For the lower limb, epidural anesthesia is recommended.(2) Debridement

Thorough and meticulous debridement to prevent infection is one of the key factors for surgical success. The requirements for debridement are stricter than for general trauma cases. If the injury is not severely contaminated, performing thorough debridement within 6 hours post-injury reliably prevents infection. Thorough debridement and preserving limb length are a contradictory unity: to save the limb, debridement must be thorough. Otherwise, infection may endanger the limb or even the patient’s life. However, excessive removal of viable tissue should also be avoided to prevent excessive limb shortening and functional impairment.

Handling of various tissues during debridement:

1. Skin Clean the skin and wound according to general principles. Circumferentially excise the skin edges, with the extent of removal determined by the injury severity. Avulsed or contused skin should be completely excised.

2. Muscles and Tendons Severely injured muscles should be excised. Tendons are more resilient and often only superficially contaminated, so excision should be cautious, typically limited to the severed ends. For tendons not requiring suturing (e.g., superficial flexor tendons of the fingers), more tissue should be excised to prevent postoperative adhesions.

3. Nerves Nerve repair is critical for restoring limb function. Nerve tissue should not be carelessly excised to avoid compromising end-to-end anastomosis. Nerves are usually superficially contaminated; after cleaning, the injured portion should not be immediately excised, and the extent of removal can be decided during suturing. For contused but intact nerves, avoid cutting them and observe for recovery or manage them in the intermediate [second] stage.

|

|

|

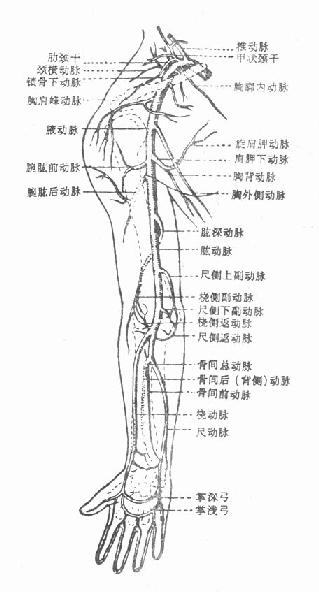

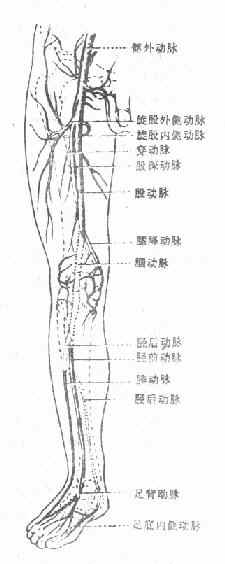

| Figure 1 Upper Limb Stirred Pulse | Figure 2 Lower Limb Stirred Pulse |

(3) Limb Perfusion

After debridement, perfuse the amputated limb. First use heparinized saline, followed by fresh heparinized blood. Approximately 50 mL of blood is used for a severed hand, while 200 mL may be required for the lower leg or forearm. The benefits include:

1. Flushing out metabolic waste and clots from small blood vessels, improving vascular anastomosis outcomes and reducing toxic effects.

2. Dilate the spasmodically closed small blood vessels and capillary networks, restoring the siphon effect of capillaries.

3. Perfusion with heparinized blood can provide nutrition to the severed limb and prolong the survival time of the detached tissue.

4. It can assess the patency of the vascular network in the severed limb. When the blood vessels of the severed limb are intact, the depressed finger (toe) pulp quickly becomes full after perfusion, and reflux fluid is observed at the venous stump. If the vascular network of the severed limb is damaged, the perfusate will quickly flow out from the severed surface or cannot be injected. Note that the perfusion pressure should be appropriate.

(IV) Treatment of Bones and Joints

1. Shortening the bone ends: The primary purpose is to facilitate debridement and the repair of nerves, tendons, and blood vessels. The amount removed should be determined based on the extent of tissue injury, but it must at least allow for end-to-end anastomosis of nerves and tendons and tension-free skin suturing.

(1) For fractures of the radius and ulna in the forearm, stainless steel pins (nails) should be used for intramedullary fixation.

(2) Severed wrist: If the wrist joint is severely damaged, parts of the ulna and radius may be sawn off, with the ulna shortened by 1 cm to facilitate the restoration of forearm rotation. For wrist arthrodesis, the cartilage surface of the scaphoid can be removed and fused with the radius in a functional position, suturing the joint capsule to preserve some wrist mobility.

(3) Distal severed palm: Typically involving metacarpal head fractures, the joint surface should be preserved as much as possible. After trimming the bone ends, temporarily fix the proximal phalanges of the index and little fingers to the corresponding metacarpals using Kirschner wires to restore the hand's framework. Remove the Kirschner wires after 2–3 weeks to restore metacarpophalangeal joint mobility, and never fuse the metacarpophalangeal joint.

(4) Severed limb at the middle-lower leg: If the tibia has an oblique fracture or is trimmed into an oblique surface, fix it with two screws or use thinner intramedullary nails inserted from the medial and lateral malleoli to stabilize the tibia and fibula.

(V) Tendon suturing. Trim the tendon stumps appropriately based on their length, deliberately staggering the ends to avoid suturing at the same level, thereby reducing adhesion and promoting functional recovery.

For severances in the forearm, wrist, or palm, accurate and thorough suturing of corresponding muscles and tendons is crucial. In the palm and wrist, avoid suturing the superficial flexor tendons to prevent adhesion with the deep flexor tendons.

Tendon suturing method: Due to time constraints and the need to suture multiple tendons, a simple, fast, and effective method is preferred. Generally, No. 4 or 7 silk thread is used for a "double cross" suture, which yields good results in most cases.

(VI) Nerve repair: Nerve recovery is critical, as it determines whether the replanted limb will regain good function. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on proper repair during the initial stage (first stage) of surgery. If the nerve length is insufficient, slight mobilization, joint flexion, or nerve transposition can be performed to achieve end-to-end anastomosis. Before anastomosis, the nerve should be trimmed with a sharp blade, removing small sections until healthy tissue is exposed. If the nerve defect is large, prioritize end-to-end anastomosis even if the ends are not entirely healthy.

(VII) Arterial and venous repair: Successful vascular repair is the key to limb survival.

1. First, perform thorough vascular debridement. Contused segments, characterized by thrombosis, subintimal or submembrane hematomas, and intimal separation, must be excised. While end-to-end anastomosis is ideal, retaining injured segments may lead to thrombosis and failure. Completely remove the affected portions without compromise. If the vascular defect after debridement is too large, autologous vein grafting is effective.

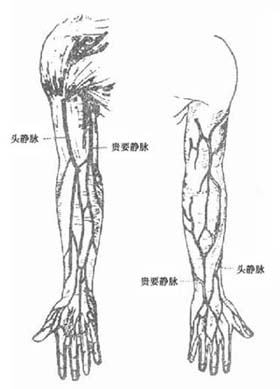

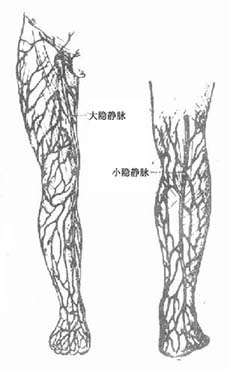

2. Graft vein diameter: Select the great saphenous vein from the healthy leg's calf or thigh based on the injury site. For larger injured vessels, use the upper great saphenous vein, dilating it with saline to the required diameter.

Since venous valves open toward the heart, ensure the graft is reversed when used for arterial repair and placed in the correct orientation for venous repair. Do not confuse the two.

3. Suture Method If the diameter of the repaired blood vessel is large (above 2mm), a two- or three-mattress fixed-point continuous suture method can be used. The mattress fixed-point suture only penetrates a small portion of the full thickness of the vessel wall, avoiding narrowing of the lumen and ensuring better alignment of the intima. For small-diameter blood vessels, such as the superficial and deep palmar arches, common digital arteries, and veins, interrupted sutures with 8-11-0 nylon thread are applied, typically requiring 6-8 stitches.

4. Suture Materials: 7-0 to 9-0 nylon threads or human hair can be used as suture materials. Experiments and clinical practice have proven that using hair to suture blood vessels with a diameter of 2mm or more in the limbs results in minimal trauma and reaction, and is convenient to operate.

5. Ratio of Artery and Vein Repair: Under normal circumstances, limbs are supplied by 1-2 stirred pulses at different levels, while several larger veins and numerous small veins and lymphatic vessels complete the return flow. After limb replantation, venous return is often insufficient, leading to an imbalance between blood supply and return. Although the venous collateral circulation system develops relatively quickly postoperatively and can gradually resolve this imbalance, early insufficient return can cause swelling of the replanted limb and even lead to failure. Therefore, as many veins as possible should be repaired. Sometimes, fewer veins can be repaired in the replanted limb. To maintain relative balance and prevent severe swelling, only one stirred pulse may be sutured, provided there is sufficient blood supply to the distal end.

During vascular repair, the lumen should be intermittently flushed with a small amount of heparin solution.

6. Timing of Releasing the Stirred Pulse Clamp: The order of repairing stirred pulses and veins is flexible, but it is preferable to anastomose the veins first. Avoid releasing the stirred pulse clamp immediately after suturing the stirred pulse without repairing the veins. Although the replanted limb may temporarily become rosy and regain circulation, the lack of venous return will cause significant bleeding at the stump. Due to coagulation, the stump will gradually stop bleeding, but the stirred pulse resistance will increase, eventually leading to complete thrombosis.

In the forearm, it is advisable to release the small stirred pulse clamp after repairing one stirred pulse and two veins to observe blood flow. Depending on the situation, other veins and another stirred pulse can be repaired. Above the wrist, if one stirred pulse and two veins are patent in the ulnar and radial stirred pulses, it is sufficient to supply circulation to the replanted limb. However, in the distal palm, where the blood vessels are smaller, the common digital stirred pulses and dorsal hand veins should be anastomosed as much as possible before simultaneously releasing the stirred pulse clamp. After circulation is restored, timely skin suturing helps protect against vascular spasm and thrombosis. Otherwise, during the suturing of other small vessels, the already sutured vessels may easily spasm or thrombose due to agitation and exposure.

After completing vascular repair and releasing the stirred pulse clamp, gently press the anastomosis site with wet gauze to stop bleeding. Carefully inspect the anastomosis site and the restoration of distal limb circulation. If there is fistula disease bleeding, continue gentle pressure with gauze. If fistula disease bleeding is significant, add 1-2 stitches. If thrombosis occurs, address it promptly, and consider re-anastomosis or venous grafting if necessary.

7. Management of Vascular Spasm: If vascular spasm occurs without thrombosis or rupture, small stirred pulse clamps can be applied to both ends of the spasm, and a needle can be inserted into the lumen to inject pressurized saline for dilation, resolving the spasm. For spasm at the stirred pulse stump, clamp the non-spasmodic segment with small stirred pulse clamps, insert a flat-head needle into the lumen from the stump, and manually push saline into the spasmodic segment to dilate it. Applying 1-2 drops of papaverine to the vessel wall or stump can significantly relieve spasm (Figures 3, 4).

| | |

| Figure 3: Subcutaneous Veins of the Upper Limb | Figure 4 Subcutaneous veins of the lower limb |

(8) Suture the skin. After successful vascular repair, the skin should be covered with a good flap as soon as possible. If there is a skin defect, free skin grafting should be used. If the suture tension is high, do not force the suture to avoid affecting limb circulation.

(9) Drainage and external fixation. Due to the severity of the injury, wound contamination, and excessive exudate, 2-3 rubber drainage strips should be placed in different locations, wrapped with ample soft dressing, and fixed with a gypsum splint. Change the dressing and remove the drainage strips after 48-72 hours.

(10) Postoperative management

1. Closely monitor the patient's overall condition. Watch for signs of poisoning, infection, renal failure, etc., and address them promptly.

2. The limb should be positioned slightly above the level of the heart. Observe the limb for swelling, color, capillary refill response, temperature, and pulse. If the severed limb is not significantly swollen but the temperature drops suddenly by 3-4 degrees or more, it often indicates partial stirred pulse obstruction, and surgical exploration should be performed immediately. Postoperatively, maintain the room temperature at 22-25°C. If the room temperature is too low, cold stimulation can cause vascular spasm.

3. Incision for swelling and tension relief. Avoid incisions whenever possible, and focus on preventive measures, such as connecting more veins. If swelling is severe with some cyanosis but circulation remains adequate, consider making an incision to relieve tension.

4. Functional exercises. Remove temporary fixation pins 2-3 weeks postoperatively and practice passive movement of the fingers and metacarpophalangeal joints. After 6 weeks, remove the external fixation for the distal severed palm and continuously practice interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joint movements. Additionally, perform appropriate wrist joint and forearm rotation exercises. For severed legs or feet, ensure the foot is fixed in a functional position and prevent deformities such as metatarsus flexion or inversion.

5. Use of anticoagulants. Apply heparin locally during vascular repair, and ensure meticulous and thorough vascular repair to prevent thrombosis. Systemic anticoagulants are not recommended. If vascular debridement is insufficient or vascular suturing is incomplete, systemic anticoagulants will not prevent vascular embolism.

6. Reoperation and functional training. After successful replantation, due to tissue trauma response and local immobilization, adhesions may form around tendons and nerves. If functional recovery is poor, consider a second surgery to release adhesions and intensify exercises, which can often improve limb function.

If metacarpophalangeal joint stiffness affects the hand's gripping function, early movement should be encouraged to prevent stiffness. If stiffness has already occurred, partial joint capsule resection and adhesion separation can be performed, followed by timely movement.

If nerves are not repaired, explore and suture them after joint mobility is restored. If the defect is too large, grafting for major nerves may yield poor results, but digital nerve grafting is more effective. If both nerves have large defects and cannot be repaired, consider using one to repair the other, such as using the ulnar nerve stump to repair the median nerve or the common peroneal nerve stump to repair the tibial nerve.

After limb replantation, intrinsic hand muscles often recover poorly. If the thenar muscles do not recover and opposition is impossible, a thumb opposition plasty can be performed.

Delayed union or nonunion of fractures should be addressed promptly with surgical bone grafting and internal fixation to facilitate limb function recovery. Follow-up should be conducted diligently, guiding the patient to persist in long-term exercises to continuously improve limb function.

In summary, for limb replantation, the priority is to ensure the patient's safety while restoring a functional limb. Follow the correct surgical sequence and methods, perform thorough debridement, properly address bone and joint injuries, repair soft tissues such as muscles and tendons, perform end-to-end nerve anastomosis, repair stirred pulses and sufficient veins, and suture the skin, with skin grafting if necessary to cover the wound. Provide proper postoperative care, identify and resolve issues promptly until the patient recovers and limb function is restored.