| disease | Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis |

Nonunion can occur on one or both sides of the vertebral body. Its spinous process may be normal, absent, or combined with other deformities such as spina bifida, but there are no clinical symptoms or slippage. This type of nonunion is called spondylolysis, which is a potential internal cause of low back and leg pain. Spondylolisthesis mostly occurs in the fifth lumbar vertebra and is less common in other locations.

bubble_chart Etiology

The spine begins to develop four cartilage nuclei (two in the vertebral body and one on each side of the vertebral arch) during the seventh week of embryonic development. These four cartilage nuclei continue to grow and unite to form a cartilaginous vertebra. Around the tenth week of embryonic development, three primary ossification nuclei appear within the primary cartilage nuclei, growing slowly and remaining separate until birth. At 1–2 years after birth, the vertebral arches begin to unite, and the spinous processes emerge. Between 3–6 years of age, the vertebral body and the bony nuclei of the vertebral arch fuse.

A fully developed spine can be divided into the vertebral body, vertebral arch, lamina, superior and inferior articular processes, transverse processes, and spinous process. Between the superior and inferior articular processes lies a narrow region known as the isthmus of the vertebral arch. If ossification in this area is incomplete or if there is a potential cartilage defect, congenital isthmic spondylolysis occurs. The defect is located between the superior and inferior articular processes, leaving the vertebral body and the posterior lamina without bony connection, linked only by soft tissues to adjacent vertebrae. If this area is developmentally weak and further subjected to trauma or strain, a fracture may occur in the weakened isthmus. The mechanism is similar to that of a fatigue fracture.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsIt can be divided into three categories:

(1) True spondylolisthesis: This refers to anterior slippage caused by nonunion of the vertebral pedicle isthmus, which is the most common type.

(2) Pseudospondylolisthesis: There is no isthmic nonunion, but rather anterior grade I displacement of the vertebral body due to degenerative changes in the spine or intervertebral discs, or other causes. This type is relatively common.

(3) Posterior spondylolisthesis: This is less common.

The common symptoms of these three types of spondylolisthesis are chronic low back and leg pain. Simple isthmic nonunion often has no significant clinical symptoms, but due to the poor stability of the lumbosacral region, local soft tissues are prone to strain. Symptoms become more pronounced in adulthood for those with slippage, with the main symptom being low back and leg pain. The location and nature of the pain vary—it may be continuous or intermittent, and some only experience pain during excessive exertion. The pain may be localized to the lumbosacral region or radiate to the hips, sacrococcygeal area, or lower limbs, such as in sciatica or spinal stenosis. In cases where cauda equina nerve paralysis occurs, pain tends to lessen with bed rest but worsens when getting up from a lying position. Occasionally, there is a sensation of internal movement during lumbar activity. Patients exhibit significant lumbar lordosis, with the torso slightly tilted forward, bringing the hypochondrium closer to the iliac crest. The buttocks protrude posteriorly, the abdomen sags, and there is a depression in the lumbosacral region with prominent posterior protrusion of the fifth lumbar spinous process. Walking is difficult, with a waddling gait. The lumbar muscles exhibit fleshy rigidity, and movement is restricted, especially during forward bending. There is marked tenderness at the fifth lumbar spinous process.

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

Imaging Findings:

For spondylolysis and grade I spondylolisthesis, clinical diagnosis is challenging, and X-ray examination is required. Commonly used projection positions include anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views.

(1) Anteroposterior View: Spondylolysis is often not easily visible on the anteroposterior view. If there is a significant defect in the pars interarticularis, when the plane of the defect is parallel to the X-ray beam, a diagonally oriented radiolucent shadow may be seen below the ring-like shadow. In cases of significant spondylolisthesis, the lower edge of the slipped vertebral body may overlap with the lower vertebral body, appearing as a crescent-shaped area of increased density. The transverse process of the L5 vertebra overlaps with the anterior edge of the vertebral body.

(2) Lateral View: For bilateral pars interarticularis defects, a diagonally oriented area of decreased bone density can be seen posterior to the pedicle, between the superior and inferior articular processes, with the posterior portion higher than the anterior portion. If the defect is unilateral, it is less likely to be visible.

In cases of spondylolisthesis, the vertebral body shifts anteriorly, with varying degrees of severity. Some cases involve complete anterior displacement of the entire vertebral body, while others show minimal displacement. Most cases involve slippage of about 1/3 to 1/4. If there is degenerative disc disease, the intervertebral space narrows.

(1) Draw a vertical line from the anterior edge of the S1 vertebral body. This line should pass through the anteroinferior edge of the L5 vertebral body. If L5 has anterior spondylolisthesis, this line will pass through the vertebral body (Ullman’s line).

(2) If L5 anterior spondylolisthesis is suspected, draw two lines: one from the posterosuperior and posteroinferior edges of L5, and another from the to be decocted later edge of the L4 vertebral body to the posterosuperior edge of the S1 vertebral body. These two lines may intersect or run parallel. Normally, the angle of intersection does not exceed 2°, and the intersection point is below the inferior edge of L4. If the lines are parallel, the distance between them should not exceed 3 mm (Ullman’s line). In cases of spondylolisthesis, the intersection point is above the inferior edge of L4. The degree of spondylolisthesis can be classified as grade III based on the angle of intersection or the distance between parallel lines (Table 1).

Table 1: Grading of Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

| Degree of Spondylolisthesis | Angle of Intersection | Parallel Distance |

| Grade I | 3°–10° | 4–10 mm |

| Grade II | 11°–20° | 10–20 mm |

| Grade III | 21° | >21 mm |

(3) Divide the superior edge of S1 into four equal parts. Normally, the posterior edges of the L5 and S1 vertebral bodies form a continuous arc. In cases of spondylolisthesis, the L5 vertebral body shifts anteriorly. A shift of 1/4 is classified as grade 1, 2/4 as grade 2, 3/4 as grade 3, and complete slippage as grade 4.

2. Differentiation of diagnosis by lateral radiographs Lateral radiographs can differentiate between true and pseudospondylolisthesis. In the former, the anteroposterior diameter of the vertebra increases; in the latter, there is no change, and degenerative changes such as narrowing of the intervertebral space, sclerosis of the adjacent vertebral margins, or lip-like hyperplasia can be observed.

(3) Oblique View The 45° oblique views (left and right) are the best positions to visualize the pars interarticularis. Normally, the vertebral arch resembles a hunting dog: the dog's mouth represents the ipsilateral transverse process, the eye represents the pedicle, the ear represents the superior articular process, the neck represents the pars interarticularis, the body represents the lamina, the front and hind legs represent the ipsilateral and contralateral superior and inferior articular processes, and the tail represents the contralateral transverse process.

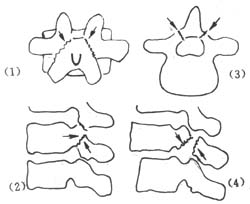

If there is a pars defect (Figure 1), a band-like area of reduced density can be seen at the neck, as if the hunting dog is wearing a collar. This indicates spondylolysis of the pars interarticularis. If spondylolisthesis is present, the superior articular process and transverse process shift anteriorly with the vertebral body, resembling a decapitated dog's head and neck (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Pars Defect and Spondylolisthesis

(1) Anteroposterior view (2) Lateral view (3) Axial view (4) Lateral view of spondylolisthesis

Figure 2: Pars Defect Resembling a Dog's Neck Wearing a Collar

CT/MRI: Partial bony defect of the pedicle, herniation of intervertebral disc, deformation of the neural foramen and spinal canal, pedicle fracture, and asymmetric vertebral arch with spinous process deviation. CT may show a "double canal" sign.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The isthmus is not separated, and there is no vertebral slippage or obvious clinical symptoms. The patient should avoid overexertion, regularly perform abdominal muscle exercises such as sit-ups to reduce lumbar lordosis, prevent slippage, or use a lumbar brace or support for protection.

If there is no vertebral slippage but the patient experiences low back and leg pain, or if the slippage is minimal without nerve compression symptoms, bone graft fixation can be performed after 3–4 weeks of bed rest.

For adolescents with significant forward vertebral slippage and nerve compression symptoms, or patients with slippage lasting no more than one year, the patient should be instructed to flex both hips and lie supine for 2–4 weeks. After the vertebrae spontaneously realign and neurological symptoms subside, bone graft fixation should be performed.

If slippage and neurological symptoms show no significant improvement after bed rest, manual reduction may be attempted. Under anesthesia, the patient should lie supine with hips and knees flexed and suspended, elevating the pelvis to allow the weight of the torso to realign the slipped vertebra.

Alternatively, the patient may lie prone while the lower limbs are gradually pulled downward to lift the pelvis off the bed. Then, both hips are flexed, and the practitioner presses the dorsal side of the pelvis with the palm, applying gradual downward force to shift the sacrum forward and reduce the slippage.

If slippage and neurological symptoms recover or improve after bed rest or manual reduction, bone graft fixation can be performed. The affected vertebral isthmus, superior and inferior articular processes, lamina, and spinous process should be fixed.

If slippage and nerve compression symptoms persist after bed rest or manual reduction, anterior vertebral bone graft fixation should be performed. Postoperatively, the patient should rest in bed for 3–4 months. If nerve compression symptoms remain unresolved after bone graft healing, laminectomy decompression may be performed.