| disease | Esophageal Achalasia |

| alias | Achalasia of Cardia |

Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder characterized by: ① absence of peristalsis in the esophageal body, ② failure or incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during swallowing, and ③ increased resting pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter. Although achalasia is a benign condition, it significantly impacts quality of life, health, and longevity. Due to dysphagia, patients may resort to various measures, including changes in posture, drinking water, and repeated swallowing, which can lead to embarrassment about eating in public, a preference for eating alone, psychological stress, and severe impairment of social activities.

bubble_chart Pathogenesis

The disease manifests as stenosis of the distal esophagus, dilation and elongation of the body, thickening of the muscular layer, particularly the circular muscle, and histological examination reveals a reduction in ganglion cells, mononuclear cell infiltration, and fibrosis in the myenteric plexus of the esophageal body. There is a decrease in the number of ganglion cells in the distal esophagus. Vagal nerve fibers exhibit myelin sheath rupture, neurofilament breakage, axoplasmic swelling, and separation of the axon-Schwann membrane and axon membrane. The number and structure of nerve cells in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve show abnormal changes. Ultrastructural examination of esophageal smooth muscle reveals microfilament shedding. Therefore, it can be seen that degenerative changes occur from the brainstem, vagal nerve fibers, myenteric plexus, down to the muscle nerve fibers, resulting in denervation of the esophagus. However, the mechanisms by which viruses, exotoxins, cancer, Chinese Taxillus Herb insects, and gastrin exert their effects, as well as the location of the primary lesion, remain unclear.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsThe incidence rate is low, approximately 1/100,000, and there may be a family history. The main symptoms include difficulty swallowing, regurgitation, and chest pain, with symptoms generally recurring over a long period. However, symptoms in young children are not obvious and are often non-specific and easily confused, which will be discussed later in the section on pediatric achalasia.

1. Difficulty swallowing has the following characteristics: ① Difficulty swallowing does not occur immediately at the start of eating; as the amount of food increases, symptoms become more apparent due to esophageal emptying disorders. ② It occurs regardless of whether the food is solid or liquid, and sometimes the difficulty swallowing is markedly different when consuming liquids. ③ The degree of difficulty swallowing is inversely proportional to the degree of esophageal dilation, meaning the more the esophagus is dilated, the less difficulty swallowing there is. ④ Esophageal emptying mainly relies on gravity, so patients may adopt various methods, such as standing while eating or constantly moving, drinking large amounts of liquid, and forcefully swallowing, repeated swallowing, holding breath after deep exhalation, etc., mainly to increase intra-esophageal pressure and force food into the stomach. ⑤ Rapid eating, consuming food that is too cold or too hot, and emotional stress can exacerbate swallowing difficulties.

2. Regurgitation occurs later than difficulty swallowing as the disease progresses, and the timing and content of regurgitation vary. In the initial stage of the disease, about 90% of patients experience regurgitation during or after meals, with the regurgitated content being the recently consumed food, in small amounts. As the esophageal body continues to expand, the esophageal capacity gradually increases, potentially exceeding 1L, and the frequency of regurgitation decreases, possibly occurring once every 2-3 days, with the amount of regurgitated material increasing and including food consumed the previous night or even several days prior, with a foul odor. Approximately 57% of patients experience regurgitation while lying down, finding regurgitated material on their pillow or bedding upon waking. Some patients may be indifferent to this, but experienced doctors should inquire carefully to gain a deeper understanding of the condition, and also ask about nocturnal aspiration due to regurgitation, causing intolerable choking and coughing, forcing the patient to sit up due to severe cough. Especially for those who develop or frequently develop bronchitis, lung infections, lung abscesses, or bronchiectasis, the possibility of esophageal reflux should be considered. The presence of blood in the regurgitated material should be taken seriously as it may indicate concurrent cancer, as about 3% of such patients develop cancer.

4. Weight loss and bleeding are due to difficulty swallowing, often causing patients to fear eating, leading to insufficient nutritional intake and resulting in varying degrees of weight loss and malnutrition. Bleeding is uncommon and mostly caused by esophageal inflammation, but the possibility of cancer should not be overlooked.

1. X-ray Examination X-ray examination is crucial for the diagnosis of achalasia, with both routine chest X-rays and esophageal contrast studies showing unique features.

(1) Routine Chest X-ray: Approximately 85% of patients show the disappearance of the gastric bubble. The posteroanterior view may reveal a tortuous, elongated, and dilated esophagus protruding into the right thoracic cavity, causing widening of the mediastinal shadow at the superior vena cava and right atrium. Sometimes, a fluid level can be seen within the shadow of the dilated esophagus. The lateral chest X-ray shows a thickened and enlarged esophageal shadow with a fluid level in the posterior mediastinum, with the trachea displaced anteriorly. Occasionally, inflammatory changes are seen in the lung fields.

(2) Esophageal Contrast Study: Before performing an esophageal contrast study, the following preparations should be made: ① If a routine chest X-ray shows significant retention in the esophagus, a gastric tube should be inserted before the contrast study to aspirate the retained material to avoid affecting the observation of the esophageal wall and motility. ② Prepare medications that may be needed during the examination, such as amyl nitrite, which can be administered immediately if necessary. ③ Prepare video recording equipment to allow repeated observation of the esophageal morphology and motility in various positions such as upright, horizontal, and right anterior oblique, especially not neglecting the supine position, which excludes the effect of gravity on esophageal emptying. Based on the esophageal contrast study, achalasia can be roughly classified into: Grade I achalasia: The lower esophagus shows significant narrowing with smooth edges, marked dilation above the narrowing, and only a small amount of barium can pass through. The esophageal dilation diameter is within 4 cm, with normal peristalsis in the proximal third, ineffective peristalsis in the middle third, and disordered or intense contractions in the distal third. The sphincter does not relax, and barium is retained in the middle third of the esophagus, which may appear spindle-shaped, bird-beak-shaped, or fistula-like. The gastric bubble is minimal or absent.

2. Endoscopy Endoscopy is highly valuable for the diagnosis of this condition. Besides observing the dilated esophagus, the endoscope can easily pass through the cardia with minimal resistance, which does not necessarily indicate a problem. However, it is essential for differential diagnosis and for formulating an appropriate treatment plan, especially when there is blood in the reflux material. Endoscopy can detect pseudoachalasia caused by cardia cancer. In cases of severe retention esophagitis, the esophageal mucosa may become hyperplastic, with polypoid changes or ulcer formation, making it difficult to distinguish from cancer. In such cases, a biopsy or brush cytology can be performed for histological or cytological examination to confirm the diagnosis. If secondary inflammatory changes in the esophagus are found, such as reddened and eroded mucosa, ulcers, leukoplakia, or candidal esophagitis, it provides clear guidance for the selection of treatment methods and timing for achalasia. When the esophagus is inflamed, the tissue is edematous and fragile, making esophageal dilation prone to perforation and myotomy likely to cause mucosal tearing and esophageal fistula. Therefore, conservative treatment should be initiated first, and surgery should be performed after the inflammation subsides. If leukoplakia is present, there is a risk of malignant transformation, and appropriate measures should be considered, including surgical resection if necessary. For candidal esophagitis, antifungal medications such as nystatin and amphotericin B should be used first.

3. Esophageal Manometry Examination: From the esophageal manometry curve, it can be observed that the lower esophageal sphincter loses its normal wave-like pattern, which is characterized by a low-pressure followed by a high-pressure curve wave (caused by the initial relaxation and subsequent contraction of the lower esophageal sphincter). Instead, it changes to a baseline-upward irregular waveform curve with normal or elevated pressure and unequal intervals, or occasionally, irregular low-pressure curves with shorter duration than normal. The esophageal body loses the rhythmic peristaltic contraction waves that appear during normal swallowing, and instead exhibits tertiary contractions or very low amplitude pressure waves, which may not even be recordable when the esophagus is extremely dilated. In cases of vigorous achalasia, the pressure waves are repetitive, not from top to bottom, and spontaneous, with amplitudes that can reach normal or abnormally high levels, possibly due to the retention of solids or liquids in the esophageal lumen. The resting esophageal pressure increases from the normal wind pressure to 2.67 kPa (20 mmHg), equal to the fundic pressure.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

1. Treatment Principles Currently, there are three methods for treating this disease: medication, dilation, and esophageal myotomy. Regardless of the method, the goal is to relieve the resistance caused by the non-relaxation, incoordination, and spasmodic contraction of the lower esophageal sphincter, facilitating esophageal emptying.

2. Medical Treatment There are few drugs for treating esophageal achalasia, with nitrites and heart pain being the more effective ones. Their pharmacological action is to reduce the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter, facilitating esophageal emptying, but their duration of action is short, and they are ineffective or less effective for some patients. Therefore, dilation or myotomy must be considered.

3. Dilation Esophageal dilation for treating esophageal achalasia has been widely used for a long time. With the development of science and technology, dilation techniques have been continuously improved and innovated, moving towards higher efficiency, safety, and comfort, making it applicable to a broader range. Except for cases with esophagitis, almost all can undergo this procedure. Since the tissue becomes fragile after inflammatory changes in the esophageal membrane during esophagitis, it is prone to tearing, causing a wide hole, making it safer to control the inflammation medically before performing this surgery. The night before the surgery, the patient should fast and cleanse the esophagus, using a thick gastric tube to clean and rinse the esophagus, sucking out residual food to avoid aspiration during the procedure and to facilitate observation. To improve the efficacy of dilation, besides the traditionally used Olive head dilator, there are now pneumatic or hydraulic forced dilations, changing from the past short duration requiring long-term dilation to now being able to provide long-term symptom relief. During the procedure, using an esophagoscope and guidewire under X-ray fluoroscopy can effectively prevent the risk of perforation caused by the placement of the dilator. Preoperatively, atropine and appropriate sedatives and analgesics are administered. Under local anesthesia, the pneumatic or hydraulic dilation strip is placed into the esophagus under fluoroscopy, and once the dilation balloon straddles the esophagogastric junction, pressure dilation is performed. The effect of dilation determines whether a second or multiple dilations are needed.

Pressure dilation is relatively safe, with only a very few cases of perforation and bleeding, often minor bleeding, clinically manifested as hematemesis or melena, aspiration, and gastroesophageal reflux (often occurring after repeated dilations). The most serious complication is esophageal perforation, with an incidence of about 3%. Depending on the timing of perforation, it can be divided into acute and subacute perforation. Acute perforation occurs immediately after the procedure. Based on experience, if persistent pain does not alleviate or even worsens 1 hour after dilation, one should be highly alert to the possibility of perforation, checking the patient for shortness of breath and subcutaneous emphysema, and taking a chest X-ray. If mediastinal emphysema or hydropneumothorax is found, the diagnosis can be confirmed, and swallowing a contrast agent to see an external fistula can clarify the diagnosis. Once diagnosed, surgical repair should be performed immediately. Generally, the perforation is on the posterior lateral wall of the lower esophagus, and after freeing the esophagus, the fistula is repaired, and a myotomy is performed on the opposite wall of the fistula to avoid postoperative reflux esophagitis, and an anti-reflux procedure can be performed simultaneously. Subacute esophageal perforation is discovered later, often with mediastinal abscess or empyema, requiring drainage. In cases of suspected occult perforation or perforation discovered later, often with mediastinal abscess or empyema, drainage is required. In cases of suspected occult perforation or confirmed by esophageal contrast without empyema or abscess, antibiotics, fasting, intravenous fluids, and nasogastric tube feeding are actively conservatively treated. If asymptomatic or confirmed by contrast that the perforation has healed after one week, oral feeding can be resumed.

4. Esophageal Myotomy This is a surgery to relieve the non-relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, potentially effectively improving esophageal emptying. The method is simple, easy to perform, with few postoperative complications and low mortality, and can be performed at any age. It has been used to treat achalasia since the 1950s.

(1) Surgical Indications

①Severe achalasia requires a more aggressive esophageal myotomy to relieve symptoms.

② Patients who have not responded to long-term conservative therapy.

③ Severe achalasia with significant esophageal dilation and curvature, making the insertion of a dilator difficult and dangerous, rendering dilation impossible or unsuccessful.

④ Frequent severe aspiration pneumonia.

⑤ Infants, young adults, or patients with vigorous achalasia who can achieve good long-term results.

⑥ Patients who cannot tolerate or are unwilling to undergo repeated dilation therapy.

(2) Surgical contraindications

① Severe cardiopulmonary insufficiency.

② Concurrent advanced stage esophageal cancer.

(3) Preoperative preparation

① Correct typical edema and electrolyte disturbances.

② Fully treat pulmonary complications and wait for the acute phase to subside.

③ In cases of severe retention esophagitis, the mucosa and submucosal tissues are fragile and prone to perforation. Medical treatment for 3-4 weeks is required, and surgery should be considered only after endoscopic examination shows mucosal healing.

④ Administer metronidazole 0.2g orally three times daily for 3 days before surgery to cleanse the esophagus.

⑤ Place a non-side-hole gastric tube the night before surgery and on the morning of the surgery to clear accumulated food, debris, and secretions from the esophagus, and retain the gastric tube to reduce the risk of aspiration during anesthesia induction.

⑥ Administer a sedative intramuscularly the night before surgery.

(4) Choice of incision: The approach for esophageal myotomy can be either thoracic or abdominal. Sometimes the thoracic approach is better, sometimes the abdominal approach, and sometimes both are suitable. Correctly choosing the incision is crucial for the success of the surgery.

① Thoracic approach: The thoracic incision provides better exposure of the cardia compared to the abdominal incision, making the incision and dissection of the muscle layer easier and more thorough. It allows for a longer myotomy, with no restriction on the upper segment of the muscle layer incision, and reduces the risk of mucosal injury. This is especially beneficial for patients with fragile scar tissue at the lower esophagus, as it avoids injury to the esophageal hiatus and prevents postoperative diaphragmatic hernia. It also allows for a wider selection of anti-reflux techniques and enables concurrent treatment of associated conditions such as esophageal leiomyoma, diverticulum, and cancer.

② Abdominal approach: The abdominal incision has the advantages of being simpler, causing less injury, and allowing for quicker postoperative recovery. It is less risky for elderly and frail patients and allows for abdominal examination and concurrent treatment of any abdominal lesions. The downside is the issue of exposure, especially in obese patients. Extensive dissection in the cardia region may not provide sufficient visibility, and due to the restriction on the upper segment of the muscle layer incision, dissection of the cardia is necessary, which may damage the cardia structure and lead to reflux. Therefore, a Nissen fundoplication must be considered to prevent reflux. However, in cases of achalasia with absent esophageal peristalsis, a full fundoplication may cause excessive obstruction.

(5) Surgical method

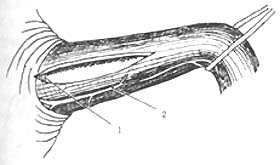

① Transthoracic approach esophageal myotomy: The surgery is performed through the 7th or 8th intercostal space via a posterolateral thoracotomy. The lung is pushed forward and upward, and the inferior pulmonary ligament is severed up to the inferior pulmonary vein. The mediastinal pleura is longitudinally incised, carefully protecting the vagus nerve, with the proximal end reaching the aortic arch and the distal end reaching the diaphragm. The esophagus is exposed and freed, then lifted with a gauze tape. The abdominal segment of the esophagus and a small portion of the gastroesophageal junction are pulled into the thoracic cavity, usually without the need to incise the hiatus. In rare cases where the gastroesophageal junction cannot be pulled into the thoracic cavity, a small incision can be made on the anterolateral part of the hiatus, but it must be sutured closed after the myotomy to prevent herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity. Holding the esophagus with the left hand, a small longitudinal incision is made in the esophageal muscle layer between the left and right vagus nerves, down to the submucosal layer. Then, using a blunt-tipped forceps, the muscle layer is bluntly dissected upward and downward to extend the myotomy incision. The proximal end should extend 2cm beyond the narrowed segment of the esophagus, and the distal end should reach the gastroesophageal junction and extend into the gastric wall, not exceeding 1cm, a few millimeters is sufficient. At the gastroesophageal junction, there is a small transverse vein that serves as a marker; the incision must not exceed this vein to avoid complications of reflux. After completing the myotomy, the incised muscle edges are freed bilaterally, reaching more than half of the esophageal circumference. Once freed, the esophageal mucosa should naturally bulge out from the incision, reducing the possibility of postoperative scarring causing the incised muscle layers to re-adhere. Some authors advocate removing a strip of the freed muscle flap. Throughout the procedure, care must be taken to protect the vagus nerve and avoid perforating the mucosa. After the myotomy and freeing, air is injected through a gastric tube to check for mucosal damage. Once confirmed that there is no fistula, meticulous hemostasis is performed, even small bleeding points should be fully controlled to prevent clot organization and contraction leading to stenosis. After completing the above steps, the esophagus is returned to the mediastinum, restoring the gastroesophageal junction to its normal abdominal position. The mediastinal pleura is sutured intermittently, and a closed drainage tube is routinely placed before closing the thoracic cavity (Figure 1).

|

| |

1. Transverse small veins of the esophagogastric junction; 2. Vagus nerve; | |

|

|

|

3 | 4 |

3, 4. Free the incised muscle edges to both sides, reaching half or more of the esophageal circumference | |

Figure 1 Esophageal myotomy

② Transabdominal esophageal myotomy: Make a longitudinal midline incision or left paramedian incision between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus, cut the triangular ligament, push the left lobe of the liver to the lower right, and expose the cardia and the diaphragmatic hiatus. Incise the abdominal membrane covering the abdominal segment of the esophagus, free the esophagus, loop a gauze band around the distal esophagus and pull it downward, expose the vagus nerve, and incise the esophageal muscle layer between the vagus nerves. The method is roughly the same as the transthoracic esophageal myotomy. Due to the deep position of the esophagus and poor exposure, it is more difficult to extend the incision of the muscle layer to a longer segment if needed.

③ Transthoracic esophageal myotomy combined with anti-reflux surgery: After completing the esophageal myotomy, pull the gauze band around the esophagus upward to lift the esophagus from the posterior mediastinum, cut the diaphragmatic attachment at the gastroesophageal junction, reflect the diaphragmatic esophageal membrane anteriorly, and free the gastroesophageal junction to the attachment point of the diaphragm, cut and ligate the ascending branch of the left gastric artery and the branches of the inferior phrenic artery. At this point, the entire gastroesophageal junction and part of the gastric fundus can be lifted into the thoracic cavity, and the fat pad at the gastroesophageal junction is removed.

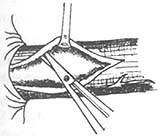

Establish Mark IV anti-reflux surgery: Retract the anterior part of the hiatus to expose the tendon of the right crus of the diaphragm, suture 4 stitches with thick silk thread through the hiatus behind the esophagus, do not tie the knots temporarily, wrap the distal 5cm part of the esophagus with the gastric fundus around 2/3 of the circumference, and fix the gastric fundus in two rows at 2cm and 5cm from the gastroesophageal junction with interrupted mattress sutures. When the second row of sutures is tied, do not cut the threads, pass them from the abdominal side to the thoracic side on both sides of the diaphragmatic tendon, place the anti-reflux mechanism under the diaphragm, tighten the two sutures and tie them. Finally, tie the 4 stitches of the diaphragmatic crus, leaving a gap at the hiatus that can smoothly pass a finger width, place a closed drainage tube, and close the chest layer by layer (Figure 2).

A B

Figure 2 Establishing Mark IV anti-reflux surgery

A. Suture the tendon of the right crus of the diaphragm; B. Fix the gastric fundus in two rows at 2cm and 5cm from the gastroesophageal junction, establishing an incomplete esophageal wrap.

④Transabdominal esophageal myotomy with anti-reflux procedure: After completing the esophageal myotomy, suture the right crus of the diaphragm behind the esophagus with thick silk thread for 3 to 4 stitches.

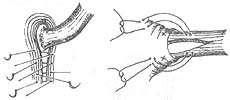

Complete fundoplication: The fundus is folded around the distal esophagus and wrapped 360°, limited to the distal 3 cm of the esophagus. The width of the fundal tunnel after wrapping should be appropriate, neither too loose nor too tight. If too loose, it will not have an anti-reflux effect; if too tight, it will cause obstruction. The criterion is that it should accommodate a 50F dilator or allow a finger to pass through smoothly (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Complete Fundoplication

A. The right crus of the diaphragm is sutured with thick silk thread behind the esophagus with 3-4 stitches; B. The fundus is wrapped 360° around the distal 3 cm of the esophagus.

Incomplete fundoplication: The fundus is folded and wrapped around the lower 2/3 of the circumference, with a length of 5 cm. The specific method involves fixing the anterior and posterior walls of the stomach to the right lateral wall of the esophagus, which is precisely the uninjured part of the esophageal muscle layer (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Incomplete Fundoplication

The fundus is folded and wrapped around the lower 2/3 of the esophagus, 5 cm in length.

(6) Surgical complications and preventive measures

① Persistent symptoms; Dysphagia persists after myotomy or recurs early, often due to insufficient myotomy, residual circular muscle fibers, or small vessels outside the membrane not being divided, resulting in incomplete natural bulging of the membrane. This situation can be detected during surgery by careful examination. After the esophageal muscle layer is incised and freed, a side-hole-free gastric tube is used to inject air, causing the membrane to bulge like a tire. If there are residual circular muscle fibers or small vessels not cut, even a few strands can form a narrow band or strip causing obstruction, which should be completely severed during surgery. Additionally, if the length of the myotomy is insufficient, or the stenosis at the cardia is not fully released, or the proximal esophageal stenosis is not completely relieved, the incision may be too low if the myotomy is performed abdominally. If performed thoracically, the incision may also be too low. If performed thoracically, the normal anatomical relationship between the cardia and the hiatus may not reach the esophagogastric junction. The insufficient length of the incision should be targeted, strictly ensuring that the proximal esophagus reaches 2 cm above the junction of esophageal stenosis and dilation, and the distal end reaches 1 cm beyond the esophagogastric junction, using the small vein in front of the cardia as a marker. Another reason for persistent symptoms is the adhesion and healing of the muscle layer edges. Therefore, during surgery, the muscle flap must be peeled beyond half the circumference of the esophagus, hemostasis must be thorough, even small bleeding points need to be addressed, and the chest should be closed only after confirming no active bleeding, with effective drainage. Accidental injury to the vagus nerve during surgery, leading to pyloric spasm and poor gastric emptying, can increase reflux. An effective preventive method is to dissect the vagus nerve and mark it with a loop. When incising the mediastinal pleura, it should be cut close to the pleura to avoid damaging the vagus nerve, and blunt dissection should be used to separate the esophagus and stomach connection. Another cause of persistent symptoms is misdiagnosis, such as reflux esophagitis secondary to peptic stenosis.

②Recurrence of symptoms after esophageal myotomy; After a period of being asymptomatic post-esophageal myotomy, symptoms may reappear due to reasons such as insufficient myotomy or re-healing, post-inflammatory scar formation around the esophagus, fibrosis around the esophagus due to scarring, and retention esophagitis. Postoperative reflux may lead to reflux esophagitis and subsequent stenosis, or complications such as cancerous obstruction. Although most patients with "S"-shaped tortuous and dilated esophagus may improve after surgery, the outcomes are worse compared to those with milder conditions. This is due to further degeneration of neuromuscular function, which exacerbates achalasia and causes symptoms to reappear. Both unresolved symptoms and postoperative recurrence require objective examinations to determine the cause, followed by either medical treatment or dilation therapy. Surgery is considered only when all other treatments fail. Preparation for esophageal resection and colonic reconstruction should be made preoperatively, as some specific reasons may not be clear until intraoperative exploration. If the original myotomy was insufficient or has healed, the incision may be extended or a new myotomy performed. If cancer is present, esophageal resection is performed. For "S"-shaped dilated and tortuous esophagus, neck and abdominal incisions are required, with esophageal stripping and cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. For peptic stenosis, some authors perform distal esophageal and gastric fundus side-to-side anastomosis via the abdomen, along with complete fundoplication. Alternatively, resection of the stenotic esophageal segment or interposition of an intestinal segment for reconstruction may be performed.

③ Mucosal perforation; Accidental cutting of the mucosa may occur during myotomy and separation on both sides of the esophagus, or during hemostasis using electrocautery, or due to severe vomiting postoperatively. Therefore, during myotomy, one should not rush. It is advisable to carefully split the sides of the esophagus first with a vertical blade, cutting and separating simultaneously to clearly visualize the tissue to be incised. When approaching the submucosal layer, the blade can be slightly tilted to reduce the sharpness of the edge, ensuring that even if the submucosal layer is reached, it does not result in an uncontrollable deep cut. When separating the sides of the esophagus, difficulties may arise due to inflammatory adhesions. Separation should be performed closer to the outer muscular layer of the mucosa, leaving a small amount of muscle on the outer layer of the mucosa rather than stripping it off. It is safer and more reliable to remove it after most of the separation is completed. If there is bleeding on the mucosa, it is best to stop the bleeding by finger pressure, avoiding electrocautery or suture ligation, as these can easily cause perforation. If a fistula is detected during surgery, it should be repaired with atraumatic sutures. Shao Lingfang advocates that the mucosa should be inverted, with the knot tied inside the lumen. It is often overlooked that during air insufflation testing, if a local bulging of the esophageal mucosa resembling a diverticulum is seen, it indicates that the mucosal layer has been cut too deeply, the mucosal layer has thinned, and is about to rupture but has not yet ruptured, posing a potential risk of perforation. In such cases, it is essential to cover and reinforce with surrounding tissue. Postoperatively, gastrointestinal decompression should be performed to avoid vomiting, and feeding should be delayed. If a fistula is diagnosed within 12 hours postoperatively, immediate surgical repair is necessary. If diagnosed later and empyema has formed, only closed thoracic drainage or open dressing changes can be performed, waiting for spontaneous healing.

④ Esophageal hiatal hernia and diaphragmatic hernia; Esophageal hiatal hernia occurs when the hiatus is cut and the supporting tissues of the hiatus are damaged unnoticed during esophageal myotomy, and thus not addressed. Increased abdominal pressure forces abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity through the ruptured hiatus, which retracts back into the abdominal cavity when abdominal pressure decreases. Prevention involves suturing the left and right crura of the diaphragm with thick silk sutures 3-4 times posterior to the esophagus to narrow the hiatus, and then fixing the cardia and esophagus to the diaphragm with several sutures.

Diaphragmatic hernia occurs when the diaphragm is cut during esophageal myotomy or anti-reflux procedures and not properly repaired, or when sudden increases in abdominal pressure due to severe coughing or vomiting cause the sutures to fail. If any inadequacies or weak points are found during finger exploration, immediate reinforcement is necessary. If hiatal hernia or diaphragmatic hernia is diagnosed postoperatively, repair should be performed. If incarceration is suspected, surgical exploration is warranted.

⑤ Reflux esophagitis: Postoperative reflux or symptoms of reflux esophagitis, such as retrosternal pain or epigastric burning, acid regurgitation, or hematemesis, inability to bend forward or lower the head after eating, and even refusal to eat due to pain. Esophagoscopy often reveals local congestion, edema, erosion, or superficial ulcers at the lower end of the esophagus. Preventive measures: Maintain the integrity of the esophageal hiatus and the esophageal diaphragmatic ligament during surgery; protect the vagus nerve; strictly adhere to the marked length for myotomy, ensuring the lower end does not extend beyond the small transverse veins on the gastric wall beneath the mucosa. Ellis firmly believes that as long as the length of the gastric wall myotomy is strictly controlled, additional anti-reflux surgery is unnecessary. He also points out that for patients with ulcer disease, performing only myotomy without additional acid-reducing procedures is inappropriate. Most scholars agree that strengthening anti-reflux mechanisms is necessary, but there is still controversy over the method of wrapping the esophagus 360° with obstructive mechanisms.

(7) Surgical Outcome: The postoperative mortality rate for this disease is extremely low, with the vast majority of authors reporting no postoperative deaths, indicating that Heller's surgery is a safe procedure. The ideal surgical outcome should be esophageal emptying without gastroesophageal reflux and long-term symptom relief. Factors affecting the outcome, apart from surgical technique, include the natural remission phase of the disease Bingben and the progressive worsening due to neuromuscular degeneration. Additionally, the surgery only relieves the obstruction at the cardia, while the effective motility of the esophagus is not treated and restored, so symptoms may still appear after rapid swallowing post-surgery. The severity of the disease also affects the efficacy; excessive esophageal dilation, severe muscular layer fibrosis, and tight submucosal adhesions mean that even after myotomy relieves the obstruction at the cardia, the dilated esophagus cannot return to its original diameter, remaining twisted and enlarged. Without effective peristalsis as a driving pump, emptying disorders persist, and the appearance of symptoms is not surprising. Therefore, although symptoms improve in advanced stage patients, the outcomes are often not very good, while surgery rarely fails in patients with mild symptoms, making early surgical treatment highly beneficial for improving surgical outcomes.

(8) Esophageal achalasia is a benign disease with an unclear cause. Current treatments, including medication, dilation, and surgery, are symptomatic. The effectiveness of drug treatment is poor and short-lived, with only two effective drugs available. Therefore, the effective treatments for this disease are esophageal dilation and surgery.

Based on the Heller surgery, there are various methods to implement anti-reflux mechanisms, such as fundoplication, vagotomy, and pyloroplasty. The Nissen fundoplication can wrap around 360° or 2/3 of the circumference, and the Mark IV surgery, among others, each has its own application and is effective in controlling reflux. Some are concerned that the 360° wrap in Nissen surgery may cause physiological obstruction. Some materials indicate that short-term 360° wrapping does not cause obstruction, but whether the further deterioration of achalasia with neuromuscular degeneration will impair esophageal emptying ability requires more long-term exploration and research in the future.