| disease | Traumatic Epistaxis |

Traumatic epistaxis is a common nasal condition caused by various external forces.

bubble_chart Etiology

1. General Trauma

Such as deep nose picking, during sneezing or nose blowing, severe cough, insertion of a nasogastric tube, and friction from foreign bodies in the nose, as well as irritation from dust or chemicals, can all cause nosebleeds. Blows, falls, and various traffic accidents are also prone to injure the nose and lead to bleeding. In wartime, blunt contusion, laceration, fractures of the nasal bone and sinuses, injuries to adjacent nasal tissues, and head trauma often cause severe nosebleeds, frequently accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, or even fatal epistaxis.

2. Barotrauma

This commonly occurs among pilots or workers in high-pressure environments, such as divers and tunnel workers, or when there is a sudden change in pressure within the nasal cavity and sinuses, which can lead to dilation or rupture of the mucosal blood vessels in the sinuses, resulting in bleeding. During negative pressure replacement therapy, if the negative pressure is too high or applied for too long, it can also rupture mucosal blood vessels and cause bleeding.

3. Surgical Injury

This is usually caused by unintentional vascular injury during surgery that goes unnoticed or by the failure to take effective hemostatic measures. For example, accidental injury to the posterior lateral nasal artery during maxillary sinus puncture through the inferior nasal meatus can lead to severe arterial bleeding. Inferior turbinectomy is particularly prone to injuring the nasopharyngeal venous plexus at the posterior end of the inferior meatus; nasopharyngeal tumor resection may damage the sphenopalatine artery or nasopalatine artery; in radical maxillary sinus surgery, bleeding may occur 6–7 days postoperatively, with the bleeding site often located at the mucosal edge of the antrostomy. During ethmoid sinus surgery, injury to the anterior or posterior ethmoid arteries, or during sphenoid sinus surgery when removing the anterior wall bone, damage to the sphenopalatine artery often forces the procedure to be interrupted due to bleeding.

bubble_chart Treatment MeasuresI. General Management

1. Management of Airway Obstruction

For nosebleeds caused by trauma, attention should also be paid to the airway condition. Appropriate measures can be taken based on the severity and urgency of the situation. For those with airway obstruction, it should be addressed first.

2. Management of Shock

For patients with severe bleeding, a thorough examination should not be conducted leisurely. In addition to immediate hemostatic measures, rapid assessment for hemorrhagic shock is essential. Once shock occurs, nosebleeds often stop on their own, but this should not be mistaken for recovery. Pay attention to pre-shock symptoms such as rapid and weak pulse, anxiety, dysphoria, pale complexion, thirst, cold sweating, and chest tightness. If blood loss reaches 500–1000 ml, ensure warmth, place the patient in a lateral position, administer oxygen, and initiate intravenous fluids immediately. A systolic blood pressure below 11.3 kPa (85 mmHg) indicates significant blood loss, and a blood transfusion should be promptly arranged. Red blood cell count and hemoglobin measurements are not useful for estimating acute nasal bleeding volume.

3. Application of Hemostatic Medicinals

Hemostatic medicinals only play a supportive role in traumatic nosebleeds. Adrenochrome and etamsylate are effective for capillary bleeding, while 6-aminocaproic acid is generally effective for coagulation disorders, and vitamin K is effective for prothrombin deficiency.

II. Hemostatic Methods

1. Topical Medicinal Hemostasis

Use 1% ephedrine saline, thromboplastin, or thrombin to tightly pack the nasal cavity for 5 minutes to 2 hours. For severe oozing, various hemostatic sponges such as starch sponge, absorbable gelatin sponge, oxidized cellulose, or fibrin can be used. These can be soaked in a thrombin solution, which is non-irritating to the nasal cavity and easily absorbed. Traditional Chinese medicinals like Puff-Ball, Carbonized Human Hair powder, cuttlebone, Sophora Flower, Bletilla striata, and Lithospermum erythrorhizon can be processed and sterilized for nasal bleeding. These cause minimal local injury and patient discomfort. Puff-Ball has strong adhesion, enhances platelet destruction, and aids in clot formation.

Apply 1% tetracaine for nasal mucosal surface anesthesia or use 1% procaine or 1% lidocaine with diluted isoproterenol for local injection to achieve anesthesia and preliminary hemostasis. Then, use instruments or chemicals to coagulate the bleeding point or small bleeding area to stop the bleeding. Instruments include high-frequency electric knives, bipolar coagulators, electrocautery devices, diathermy, or focused laser beams. Chemicals include 30–50% silver nitrate, 50% trichloroacetic acid, or pure chromic acid. The goal of coagulation is to form a distinct white membrane. Avoid rubbing the cotton swab on the mucosa or allowing excess chemical to flow onto healthy mucosa. Also, avoid simultaneous coagulation on corresponding areas of both sides of the nasal septum to prevent perforation.

3. Packing Hemostasis

(1) Anterior Nasal Packing: This is the first-line treatment for severe nosebleeds. The packing material is sterile Vaseline gauze. Packing should proceed gradually from back to front and top to bottom in a folded manner to prevent the gauze from slipping into the nasopharynx. The packing should be removed within 24 hours to avoid complications such as sinusitis or otitis media. If prolonged packing is necessary, antibiotic powder should be added to the packing material. Balloon compression hemostasis is an improved method of anterior nasal packing, where a silicone membrane balloon with a ventilation hole is placed at the potential bleeding site in the nasal cavity. The balloon is inflated to exert pressure and stop the bleeding.

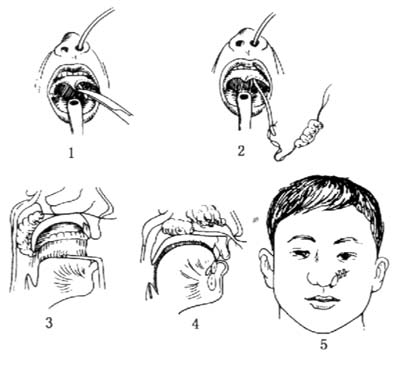

(2) Posterior Nasal Packing: If blood continues to flow into the pharynx or gushes out from the opposite nostril after anterior nasal packing on the bleeding side, it indicates that the bleeding site is located in the posterior part of the nasal cavity. In this case, posterior nasal packing should be performed. First, roll Vaseline gauze into a pillow or conical shape, slightly larger than the patient's posterior naris, with both ends left with double threads approximately 25 cm long. Before packing, constrict and anesthetize the nasal mucosa. Insert a catheter through the anterior naris along the nasal floor until it reaches the pharynx, then pull the tip out from the oral cavity. Tie the double threads of the packing material to it, and retract the tail end of the catheter to pull the double threads of the packing material out. This allows the packing material to be guided from the oral cavity into the nasopharynx, tightly blocking the posterior naris. Additionally, perform anterior nasal packing with Vaseline gauze (Figure 1). Secure the double threads at the anterior naris with a gauze roll, and leave the double threads in the oropharynx for later removal of the packing material. Posterior nasal packing should generally be removed within 24–36 hours to avoid complications such as acute suppurative otitis media, acute sinusitis, and skull base osteomyelitis.

Figure 1 Posterior Nasal Packing (1. The catheter is pulled out of the mouth; 2. The long thread of the packing is tied to the end of the catheter outside the mouth; 3. The packing enters the nasopharynx; 4. The packing tightly blocks the posterior naris, partially enters the nasal cavity, and performs nasal packing; 5. The two long threads of the packing are tied to the gauze roll at the anterior naris for fixation)

4. Stirred Pulse Ligation

If the above methods fail to control severe traumatic nasal bleeding, stirred pulse ligation should be performed. Before ligating the stirred pulse, the responsible vessel for the bleeding must be identified. The blood supply to the nasal region originates from two systems: the external carotid stirred pulse and the internal carotid stirred pulse. If the bleeding area is above the lower edge of the middle turbinate, it is a branch of the internal carotid stirred pulse that is bleeding, and the anterior ethmoidal stirred pulse should be ligated. If the bleeding area is below the lower edge of the middle turbinate, it is a branch of the external carotid stirred pulse that is bleeding, and the external carotid stirred pulse or the internal maxillary stirred pulse should be ligated. The anterior ethmoidal stirred pulse can generally be ligated with silk thread or clamped with a small silver clip. After ligation, it should not be severed to prevent the stump from retracting into the bony canal, which could lead to complications such as intraorbital bleeding or proptosis if the ligature slips.