| disease | Pharyngeal Scar Stenosis |

It is the scar adhesion between the soft palate, pharyngeal arch, and the posterior pharyngeal wall, which narrows, constricts, or obstructs the normal passage between the nasopharynx and oropharynx. Nasopharyngeal stenosis is often caused by scar tissue. Patients have a basic anatomical structure, usually resulting from trauma, corrosive injuries, or specific infections such as syphilis, leprosy, scleroma, etc. Excessive injury to the mucous membrane during adenoidectomy can also lead to cicatricial stenosis, while congenital cases are rare. Nasopharyngeal atresia is mostly due to congenital developmental abnormalities and often coexists with choanal atresia, with acquired cases being uncommon.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Depending on the degree of narrowing, mild cases may be asymptomatic. Severe cases may present with {|###|}stuffy nose{|###|}, reduced or lost sense of smell, snoring, mouth breathing, nasal voice, or slurred speech. Nasal secretions often accumulate in the nasal cavity and are difficult to expel. If the Eustachian tube is affected, hearing loss or otitis media may occur.

Examination{|###|} Upon opening the mouth, adhesions between the soft palate and the posterior pharyngeal wall can be seen, often with the disappearance of the uvula. Behind this area, there is usually a small passage leading to the nasopharynx. A curved probe can be inserted through the opening to assess the size of the passage and the extent of scar tissue upward. Manual palpation from inside the mouth can roughly determine the range of adhesions and the thickness of the scar tissue. The nasal cavity often contains significant secretions, and placing a small amount of cotton at the anterior nostrils can help detect whether a passage to the nasopharynx exists. If there is a small opening between the soft palate and the posterior pharyngeal wall, an indirect nasopharyngeal mirror examination can be performed to evaluate the extent and severity of scar adhesions in the nasopharynx.

Lateral soft tissue radiography or nasal iodized oil contrast imaging can provide significant assistance in diagnosis and treatment.bubble_chart Treatment Measures

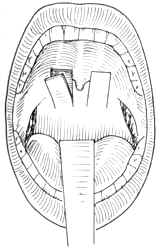

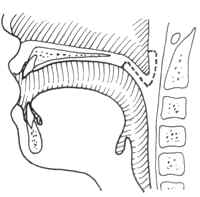

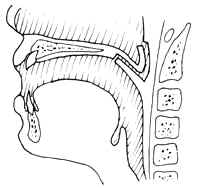

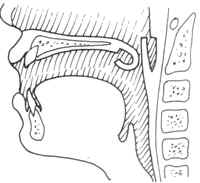

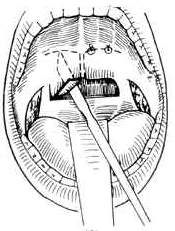

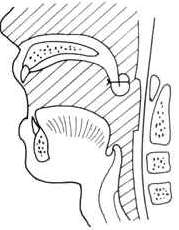

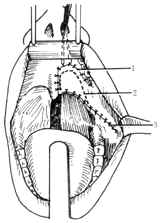

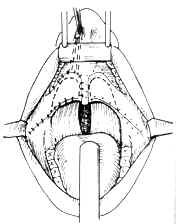

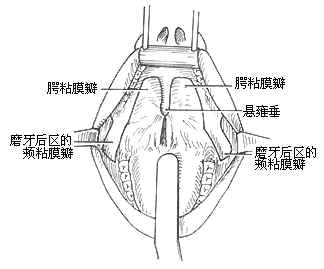

The primary treatment for nasopharyngeal stenosis is surgical intervention. The choice of surgical method depends on the degree of stenosis, including simple dilation, catheter or diaphragm separation, skin grafting, mucosal flap transfer, soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall plasty, and stringing. For patients with grade I membranous atresia, mucosal flap inversion can also be used for reconstruction, creating a mucosal flap with a downward base in the oropharynx and an upward-based mucosal flap in the nasopharynx. The nasopharyngeal mucosal flap is rolled forward to cover the wound on the soft palate, while the oropharyngeal mucosal flap is rolled backward to cover the wound on the posterior pharyngeal wall (Figures 1-4). If a small hole remains in the middle of the soft palate with thin and less firm scar tissue, a curved probe is first used to assess the thickness of the adhesion through the hole. Then, mucosal flaps with upward bases are created on the posterior pharyngeal wall on both sides of the uvula. The length of the mucosal flaps should approximate the extent of the adhesion. When the mucosal flaps are rolled upward, they can completely cover and fix the wound on the nasopharyngeal side of the soft palate (Figure 5).

Figure 1: Frontal view of the mucosal flap with a downward base

Figure 2: Lateral view of the mucosal flap incision

Figure 3: Formation of the flap membrane

Figure 4: Alignment of the flap membranes in preparation for suturing

Figure 5: Mackenty method

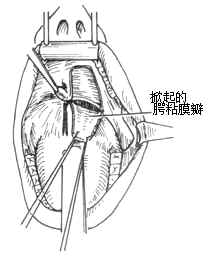

(1) Frontal view (2) Sagittal viewIf the scar is thick and firm, making it difficult to roll the soft palate mucosal flap, or if the adhesion is extensive and involves the oropharynx, in addition to using the soft palate mucosal flap, the buccal mucosal flap from the retromolar area should be rotated to cover the entire separated wound. Bilateral adhesions require staged surgery as follows: On one side of the soft palate, a rectangular mucosal flap is created (Figure 6), with the base extending downward to the pharyngeal mucosa. Care must be taken not to penetrate the soft palate muscle layer into the nasopharynx when elevating the flap. The scar tissue between the base of the mucosal flap and the soft palate is excised horizontally, and the adhesion between the soft palate and the posterior nasopharyngeal wall is separated to advance the soft palate forward (Figure 7). The soft palate mucosal flap can extend from the lower edge of the soft palate into the nasopharynx to cover the wound on the posterior pharyngeal wall. A traction suture is placed on the free edge, passed through the nasal cavity, and fixed outside the anterior naris, with additional fixation using nasopharyngeal packing. The wound on the anterior wall of the soft palate is covered by rotating a rectangular mucosal flap from the buccal mucosa of the retromolar area, and the incision in the retromolar buccal mucosa is sutured (Figure 8). The contralateral surgery is performed after the wound on the initial side has healed (Figure 9).

Figure 6: "Z"-shaped incision of the mucosal flap

Figure 7: Formation of the palatal mucosal flap

Figure 8: Suturing and fixation of the mucosal flap

Figure 9: Contralateral plasty performed using the same method