| disease | Open Hand Injury |

| alias | Hand Open Injury |

The hand has the most frequent contact with the external environment, making it susceptible to injury. In orthopedic emergency departments, hand injuries account for approximately one-quarter of the total number of patients, with open hand injuries making up two-thirds of all hand injuries. The prevention and treatment of hand injuries are crucial topics in the field of surgery. Special emphasis must be placed on the early management of complex emergency hand injuries. For such injuries, an active approach is essential. Correct early treatment can often avoid the need for intermediate stage (second stage) surgery. If the injury is too severe to be repaired early, efforts should still be made during the initial surgery to create conditions for advanced stage repair.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Initial stage [first stage] surgical management

Initial stage [first stage] surgical management is the main step in managing hand injuries and also the foundation for future treatments. The principles of management are: early and thorough debridement to prevent wound infection; repair injured tissues as much as possible to maximize the preservation of hand function. Specific steps include: ① debridement ② tissue repair ③ wound closure ④ dressing and immobilization. Pain relief should be administered promptly, along with tetanus antitoxin and anti-infective drugs.

(1) Anesthesia Surgery should be performed under adequate anesthesia. For single finger injuries, digital nerve block anesthesia can be used; for wounds involving the palm, back of the hand, or multiple fingers, wrist nerve block can be performed; for larger wounds, brachial plexus anesthesia is preferable.

(2) Debridement The purpose of debridement is to remove dirt and foreign bodies from the wound, excise non-viable tissue, and convert a contaminated wound into a clean wound (not sterile) to prevent infection. The specific method is the same as described in the general trauma chapter. However, it is emphasized:1. Thorough wound cleaning is crucial. Although the method is simple, it is an important step in preventing wound infection and should be performed with great care.

2. The principles of debridement should be followed, proceeding from the outside in and from superficial to deep layers in a planned manner. The hand has a complex, delicate, and richly vascularized structure, so debridement should aim to preserve as much vascularized tissue as possible and minimize skin edge excision.

3. While performing planned debridement, a comprehensive and systematic examination of injured tissues should be conducted to assess the extent and severity of injury. If necessary, release the tourniquet to observe the circulation of tissues (such as muscles, skin, etc.) to formulate a comprehensive surgical plan.

(3) Management of injured tissues For routine hand injuries, as long as conditions permit, initial stage [first stage] repair of injured tissues should be performed as much as possible. This is because the anatomical relationships are clear at this stage, secondary degeneration is minimal, making surgical procedures easier, with better outcomes and faster functional recovery. The order of management is:

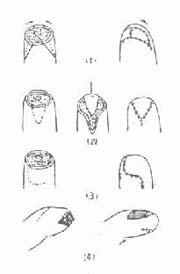

Figure 1 Cross Kirschner wire fixation method

1. Management of bones and joints. As with general debridement principles, bone fragments should be preserved as much as possible, removing only completely detached small bone fragments. After reduction, cross Kirschner wire fixation is used (Figure 1). Long oblique fractures can also be fixed with compression screws. Do not perform intramedullary fixation through adjacent joints. Suture the open joint capsule.

3. Injury to one side of the digital artery or common digital artery usually does not significantly affect finger circulation and may not require repair. Complete severance of both digital arteries often results in insufficient blood supply to the finger and requires repair.

(4) Wound closure Wound closure is an important measure to prevent wound infection. Only by closing the wound on the basis of thorough debridement can the exposed deep tissues be protected, bacterial invasion be prevented, and infection be avoided. The hand has rich circulation and strong resistance to infection, so the time limit for wound closure can generally be extended to 12 hours after injury, but this is not fixed and can be adjusted based on the nature of the injury, degree of contamination, and ambient temperature. Methods of wound closure include:

1. Direct suturing If there is no or minimal skin loss, direct suturing can be performed, but tension suturing should be avoided. For linear wounds crossing joints, perpendicular to palmar creases, or parallel to finger webs, local "Z" plasty should be performed to avoid scar contracture.

2. Free skin grafting If the base of the skin defect still retains a well-vascularized tissue bed, and bones and tendons are not exposed, free skin grafting can be performed. Small areas of exposed bone or tendon can be covered with nearby soft tissue (muscle, fascia) or soft tissue flaps before grafting. Medium-thickness skin grafts are generally preferred, while full-thickness grafts can be used for fingertips and palms.

3. Flap coverage For larger areas of exposed bone or tendon, flap coverage is often required.

|

|

|

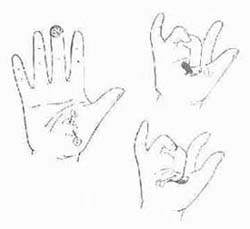

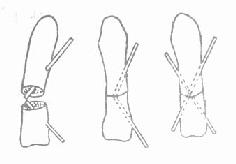

| Figure 2 Various local flap designs for fingertip amputation | Figure 3 Thenar flap |

| (1) Triangular flap at the fingertip (2) V-Y flap | ① Flap pedicle at the proximal end |

| (3) Dorsal rotation flap (4) Dorsal bipedicled advancement flap | ② Flap pedicle at the ulnar side |

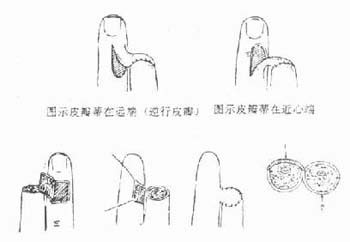

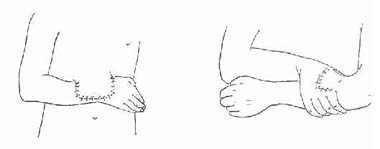

(2) Cross-finger flap (Figure 4) is formed using the skin from the dorsal side of an adjacent finger, commonly used to cover defects at the fingertip or finger pad.

① Free skin grafting ② Dorsal finger flap transferred to the volar side of the fingertip

Figure 4 Cross-finger flap

(3) Distant flap Large areas of exposure require large distant flaps, commonly including the cross-arm flap, abdominal flap, and iliolumbar flap (Figure 5). With the rapid development of microsurgery, various free flaps have been continuously designed over the past decade, providing more options for hand wounds. Flaps more suitable for the hand include the forearm flap, saphenous flap, medial and lateral arm flaps, groin flap, and dorsalis pedis flap, which can be selected based on specific conditions.

(1)Abdominal flap (2)Cross-arm flap

Figure 5 Distant flap

(5)Dressing and fixation: Dressing and fixation are crucial for hand injuries. For bone and joint injuries, the hand should be dressed and fixed in a functional position postoperatively. For tendon and nerve injuries, the hand should be dressed and fixed in a tension-free position after repair.