| disease | Diffuse Malignant Mesothelioma |

| alias | Pleural Mesothelioma |

Pleural mesothelioma includes the prognostically favorable benign fibrous mesothelioma and the diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma, the latter being considered the most prognostically unfavorable tumor in the chest, for which there are still no effective treatment measures available to date.

bubble_chart Etiology

All types of asbestos fibers are almost all associated with the mechanism of disease of mesothelioma, but the risk of self-sustaining fibers is not the same. The most dangerous is exposure to crocidolite, and the least dangerous is exposure to chrysotile. The latent period from first exposure to asbestos to the onset of disease is generally 20 to 40 years, and the incidence of mesothelioma is directly proportional to the duration and severity of asbestos exposure.

If the content of erionite in the atmosphere increases, people inhaling this powdered zeolite can also cause mesothelioma. There are also reported cases of pleural mesothelioma caused by exposure to radiation, with the time from radiation exposure to the discovery of pleural mesothelioma ranging from 7 to 36 years, with an average of 16 years. Nitrosamines, glass fibers, hydrogen cyanide, thorium oxide, beryllium, and other lung diseases (such as subcutaneous nodules and chemical substances and lipid aspiration pneumonia) can all lead to pleural mesothelioma.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

In the early stages of malignant mesothelioma, numerous white or gray granules, nodules, or thin plaques are visible to the naked eye on the normal or opaque visceral or parietal pleura. As the tumor progresses, the pleural surface becomes increasingly thickened, covered with nodules, and the tumor nodules extend in all directions, forming continuous sheets that encase the lung, causing it to shrink and leading to the collapse of the affected side of the chest wall. In advanced stages, the tumor may involve the diaphragm, intercostal muscles, mediastinal structures, pericardium, and the contralateral pleura. Autopsy findings reveal hematogenous metastases in 50% of patients, although these are rarely mentioned clinically.

Malignant mesothelioma has two pathological anatomical types: ① Solitary fibrous pleural mesothelioma. It grows from the visceral pleura, either as a flat plate or pedunculated, and clinical symptoms arise due to their expansion, compressing and displacing intrathoracic structures. If diagnosed early, surgical treatment is possible. ② Diffuse mesothelioma. This type invades the lung lobes, infiltrates the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, and can involve the pericardium and major blood vessels through the mediastinal pleura.The microscopic appearance of malignant mesothelioma is distinctive, with various markedly different tissue components present in individual tumor nodules or nodules that appear identical macroscopically. The histopathological classification of malignant mesothelioma includes epithelial, fibrous (stromal), and mixed types. The epithelial type tumor cells exhibit various structures, such as papillary, tubular, tubulopapillary, band-like, or sheet-like. Polygonal epithelial cells have many long, slender, and branched microvilli on their surface, desmosomes, bundles of elastic filaments, and intercellular spaces (Figure 2). Fibrous-type cells are spindle-shaped, with parallel configurations, oval or elongated nuclei, and well-developed nucleoli (Figure 3). The mixed type combines both epithelial and fibrous tissue structures. The more samples taken from different parts of a tumor mass during biopsy, the more likely it is to be classified as mixed type.

Figure 2 Malignant epithelial pleural mesothelioma (left) and malignant pleural mesothelioma (right)

Figure 3 Malignant fibrous mesothelioma

Male, 81 years old, collagen bundles and various atypical cell membranes.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsMalignant pleural mesothelioma is more common in men than in women (2:1). Most patients are between 40 and 70 years old, with an average age of 60 years in foreign patients and only 45.2 years in our country. The initial symptoms are most commonly chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath. About 10.2% of patients present with fever and sweating, and 3.2% of patients primarily complain of arthralgia. Due to diaphragmatic involvement, chest pain can radiate to the upper abdomen and the affected shoulder. Approximately 50-60% of patients have a large amount of pleural effusion accompanied by severe shortness of breath, with bloody pleural effusion accounting for 3/4. Patients without a large amount of pleural effusion experience more severe chest pain. Weight loss is common. Some patients experience periodic hypoglycemia and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, but these signs are more common in benign mesothelioma.

Epithelial and mixed-type pleural mesotheliomas are often accompanied by a large amount of pleural effusion, while the fibrous type usually has little or no pleural effusion. Epithelial-type patients seem to have more involvement of supraclavicular or axillary lymph nodes and extension to the pericardium, contralateral pleura, and peritoneum; the fibrous type often has distant metastases and bone metastases.

Radiological signs: Common chest X-ray findings include pleural effusion, often occupying 50% of one side of the chest cavity. The ipsilateral lung is encased by tumor tissue, the mediastinum shifts toward the side with the tumor, and the affected chest cavity becomes smaller. In advanced stages, chest X-rays show no mediastinal widening, pericardial effusion causing cardiac enlargement, visible soft tissue shadows, and rib destruction.

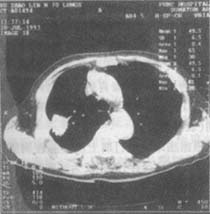

On routine chest X-rays, pleural diseases can be masked by pleural effusion. For evaluating patients suspected of malignant pleural mesothelioma, CT scans are most useful. CT can show pleural thickening with irregular nodular inner margins, distinguishing malignant pleural mesothelioma from other pleural thickening lesions. Due to the presence of fibrous tissue, tumor tissue, and pleural effusion, the major lung fissures are significantly thickened. If invaded by the tumor, the lung fissures may appear nodular. CT can usually detect pulmonary nodules, the degree of lung encasement and shrinkage by the tumor, and chest wall collapse (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Right-sided diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma

The tumor grows from the parietal pleura and extends into the lung fissure

Pleural effusion: The pleural effusion associated with mesothelioma is exudative, with 50% being serosanguinous. If the tumor is large, the glucose content and pH of the pleural effusion may decrease. Due to the high content of hyaluronic acid (>0.8mg/ml), the pleural effusion is more viscous. The pleural effusion generally contains normal mesothelial cells, well-differentiated or undifferentiated malignant mesothelial cells, and varying amounts of lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cytological examination of the pleural effusion aids in diagnosis.

Routine laboratory tests: Thrombocytosis may be observed during the course of the disease, with individual reports of platelets as high as 1000×109/L. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen is elevated in some patients, and serum immunoelectrophoresis shows elevated IgG, IgA, or IgM, the reason for which is unclear. Serum alpha-fetoprotein is generally normal.

Patients with exudative pleural effusion, especially those with a history of asbestos exposure, should be considered for the diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Chest CT can confirm the diagnosis, and chest CT examination can determine whether there is calcification of the pleura or destruction of bone structures. When the tumor invades the diaphragm and chest wall, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior to CT (Figure 1). Although pleural fluid cytology, pleural biopsy, and pleural fluid cell block sections can make a malignant diagnosis, they cannot differentiate between metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pleura and malignant mesothelioma.

Figure 1 MRI: Malignant pleural mesothelioma of the right lower chest wall

Malignant pleural mesothelioma is also present in the visceral pleura of the posterior segment of the left lower lobe of the lung (surgically confirmed)

If three techniques have been developed in the past 10 years, they are relatively certain to aid in the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. These three techniques are histochemical staining with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) solution, immunoperoxidase testing for keratin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and electron microscopy. For these tests, biopsy specimens must be immediately fixed in neutral formalin solution, and another small piece of tumor biopsy specimen should be placed in glutaraldehyde solution for electron microscopy.

PAS staining is the only reliable histochemical method that can distinguish malignant pleural mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma. Although the characteristics of various metastatic adenocarcinomas are different, the appearance of strongly positive vacuoles after amylase digestion can diagnose adenocarcinoma rather than malignant pleural mesothelioma.

The immunoperoxidase technique uses antibodies against keratin and CEA, which is also effective in distinguishing malignant pleural mesothelioma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. For immunoperoxidase staining of CEA, malignant pleural mesothelioma generally stains lightly or not at all. In contrast, adenocarcinoma stains moderately to heavily. In addition, immunoperoxidase studies of keratin also show significant differences between mesothelioma and adenocarcinoma. Currently, eight markers have been identified for differentiation: tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 (B72.3), Leu-Mi, Vimentin, thrombomodulin, mucin components, and positive cancer antigens have 100% specificity and sensitivity for adenocarcinoma. Since CEA testing often yields false negatives, it is best to choose two tumor markers, usually CEA and B72.3. If both are positive, they have 100% specificity and 88% sensitivity for adenocarcinoma; if both are negative, they have 100% specificity and 97% sensitivity for mesothelioma.

Electron microscopy is also useful in distinguishing malignant pleural mesothelioma from metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pleura. Malignant pleural mesothelioma differs from adenocarcinoma originating from the lung, breast, and upper gastrointestinal tract in that its surface microvilli are thin, long, and branched, with abundant tonofilaments, and lacks microvilli roots and lamellar bodies; metastatic adenocarcinoma originating from the ovary and uterine endometrium has intrinsic tissue changes, including abundant mucin droplets, numerous cilia, and dense nuclear granules, which are absent in mesothelioma. The villi of adenocarcinoma are short and thick.

The pathological diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma remains controversial. Although malignant mesothelioma is classified with soft tissue fleshy tumors, only 20% are histologically pure fleshy tumors. 33-50% of malignant pleural mesotheliomas are histologically epithelial or tubular and papillary, while another 30% are mixed epithelial and fleshy tumors. Most pathologists believe that only patients with fleshy tumors or mixed tissue can be diagnosed with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Based on comprehensive special staining and electron microscopy data, experienced pathologists are also willing to diagnose malignant pleural mesothelioma in patients with epithelial types.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

To this day, there is still no effective treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma. However, through certain treatment methods, a small number of patients both domestically and internationally have survived for more than 5 years, with the longest survival reaching 22 years. Most believe this may be related to the natural survival time and staging of the tumor. According to the Butchart staging system, malignant pleural mesothelioma is divided into four stages (Table 1).

Based on clinical manifestations, Stage I epithelial-type malignant pleural mesothelioma has the potential for long-term survival, hence radical pleuropneumonectomy is recommended for these patients. For Stage II, III, and IV epithelial-type and other pathological types, whether treated or not, with radical or palliative surgery, and regardless of the efficacy of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the survival curves post-treatment are essentially the same, with an average survival time of 18 months, and about 10% of cases surviving more than 3 years.

Table 1 Clinical Staging of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma

| Stage I | Tumor confined to the parietal pleura, involving only the ipsilateral pleura, lung, pericardium, and mediastinum |

| Stage II | Tumor invades the chest wall or involves mediastinal structures, namely the esophagus, heart, and contralateral pleura. Lymph node involvement is limited to the chest (N2) |

| Stage III | Tumor penetrates the diaphragm to involve the peritoneum, invades the contralateral pleura and bilateral chest, and involves extra-thoracic lymph nodes |

| Stage IV | Distant hematogenous bone metastasis |

1. Palliative Treatment The pleural effusion in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma often reaccumulates quickly after being aspirated. Injecting chemical agents into the pleural cavity to cause pleural adhesions can control the effusion in most patients. If pleurodesis fails or in patients scheduled for diagnostic thoracotomy, pleurectomy should be considered.

Malignant pleural mesothelioma can spread along the puncture site, chest tube tract, and thoracotomy incision, but the subcutaneous deposits rarely cause symptoms and therefore do not require treatment. If treatment is given, these subcutaneous nodules can serve as indicators for observing treatment efficacy.

Chest pain in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma is the most difficult symptom to manage, especially severe in advanced stages, persisting all day without response to radiotherapy. Adequate sedative and analgesic agents, including opioids, should be administered to alleviate pain and help the patient through their final moments.

2. Surgical Treatment Currently, there are various surgical measures for treating malignant pleural mesothelioma. The first is extended pleuropneumonectomy, which involves the radical resection of the affected part of the chest wall, the entire lung, the diaphragm, the mediastinum, and the pericardium. This procedure is only applicable to stage I functional epithelial malignant pleural mesothelioma cases. Severe cardiopulmonary impairment is a contraindication for this surgery. A standard posterolateral thoracotomy incision is made in the fourth intercostal space, and the tough and thickened parietal pleura and tumor nodules are bluntly dissected from the chest wall together. This operation can cause extensive bleeding, which can be controlled by compression, electrocautery, and ligation to achieve thorough hemostasis. Then, the mediastinal pleura is separated from the top of the hilum, and the paratracheal lymph nodes are removed. Anteriorly, at the level of the lung apex, the internal mammary artery and vein are ligated, and all visible lymph nodes along with these vessels and pleura are removed from the anterior chest wall. Posteriorly, the paraesophageal and carinal lymph nodes are removed. The pericardium is incised from the corresponding posterior left side. At this point, the decision is made whether to remove the lung or the diaphragm first, depending on the site of tumor invasion and its extent. The hilum and vessels and bronchi are transected, and the procedure is handled as in any intrapericardial (extended) pneumonectomy. The lower part of the pleura is not as low as the diaphragm, and after freeing the pleura, the diaphragm can be removed outside the lower pleural fold. For adequate exposure, a second incision is usually made in the 8th to 10th intercostal space on the same side. Because the patient is placed in a lateral position during the surgery, after the diaphragm is removed, the liver tends to shift from above into the mediastinum, compressing the inferior vena cava and causing cardiac and circulatory disturbances. After the diaphragm is removed, the defect can be repaired with Maxlex mesh or Dacron silicone material, and some use dura mater for repair. Regardless of the material and technique used, it is essential to ensure a tight seal to prevent blood or pleural fluid from flowing into the abdominal cavity; the diaphragm substitute should be securely sutured to the residual edge of the diaphragm with continuous sutures to prevent abdominal organs from protruding or herniating into the thoracic cavity. Before closing the chest, chest tubes should be connected to a suction device for negative pressure drainage. The surgical mortality rate for extended pleuropneumonectomy is 10-25%, but its efficacy is not better than pleurectomy, so it is not recommended for widespread use.

The second surgical treatment is pleurectomy, which is not curative because the tumor often involves the underlying lung. This surgery does not improve the survival time of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma, but it seems to control pleural effusion and improve the quality of life. In addition, chest pain caused by malignant pleural mesothelioma can sometimes be relieved after pleurectomy. For cases suspected of malignant pleural mesothelioma, pleurectomy should be considered when planning a diagnostic thoracotomy biopsy. Pleurectomy can also be considered for cases with a large amount of pleural effusion and failed chemical pleurodesis. As mentioned above, pleurectomy is a palliative surgery aimed at removing the parietal pleura and part of the visceral pleura to prevent the recurrence of pleural effusion and alleviate chest pain symptoms. Generally, a posterolateral thoracotomy incision is made at the 6th intercostal space, and the parietal pleura and part of the visceral pleura involved by the tumor are bluntly or sharply dissected and removed from the chest wall and lung. This procedure may cause damage to the spinal cord or brachial plexus due to heat conduction. It is best to use a high-frequency argon beam coagulator when removing tumors near the spine and the apex of the thoracic cavity. Special care should be taken to preserve the nerves and blood vessels at the apex of the thoracic cavity and mediastinum. As much tumor tissue as possible should be removed to reduce its volume, which is beneficial for postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy. A closed thoracic drainage with negative pressure suction is placed at the end of the surgery.

3. Chemotherapy Anthracyclines are considered effective against malignant pleural mesothelioma, followed by cisplatin, mitomycin, cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil, methotrexate, and vincristine. Currently, anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy is commonly used. In recent years, statistics from domestic and international studies show that the overall response rate of doxorubicin-based chemotherapy regimens is about 20%, with the best being CAO (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine). The overall response rate of various treatment regimens without anthracyclines is 21%, with the best being mitomycin plus cisplatin (MP). Cisplatin combined with high-dose methotrexate. Chemotherapy continues until the condition does not worsen.

4. Radiotherapy External radiotherapy is disappointing for malignant pleural mesothelioma, but extensive external radiotherapy is considered effective in relieving chest pain and controlling pleural effusion in some cases, but it has no effect on the disease Bingben itself. External irradiation above 40Gy has palliative effects, with a 67% relief rate at 50-55Gy. A few patients survive for more than 5 years, but almost all patients still die from recurrence or metastasis.

Intracavitary radiotherapy has some response in a few cases of malignant pleural mesothelioma, and a few patients have long-term efficacy, offering a glimmer of hope. The main isotope used is radioactive gold, which has an affinity for cells covering the serous cavity, making it particularly suitable for treating diffuse tumors such as mesothelioma. Its main therapeutic effect is due to the radiation of beta particles, which have a penetration depth of 2-3mm and are most effective for early-stage tumors, but early-stage malignant pleural mesothelioma is difficult to detect. In the past, colloidal 198gold was injected into the pleural cavity, and a few cases survived for more than 5 years. Due to the difficulty in protection, it is rarely used now.

Combination therapy and intraoperative irradiation or isotopes 132I, 192Ir, 32P implantation into the cavity, and postoperative external radiotherapy plus chemotherapy have not resulted in long-term cures.

5. Comprehensive Treatment In recent years, comprehensive treatment measures have been adopted, including post-thoracic membrane pneumonectomy and CAP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide 600mg/m2, doxorubicin 60mg/m2, and cisplatin 75600mg/m2, administered continuously for 5 courses, with a 3-week interval between each course). Postoperative external beam irradiation of 55Gy was applied to the original tumor site or residual tumor location. Analysis of 53 patients who received comprehensive treatment showed a perioperative complication rate of 17% and a surgical mortality rate of 5.8%. The average survival time was 16 months (1-8 years). The 1, 2, and 3-year survival rates for 31 patients with epithelial type were 7%, 50%, and 2% respectively; the 1 and 2-year postoperative survival rates for patients with mixed and fleshy tumor types were 45% and 7.5%, with no cases surviving beyond 25 months. Patients with local mediastinal lymph node metastasis had shorter survival times compared to those without lymph node metastasis. The 5-year survival rate for patients with epithelial type mediastinal lymph stagnation of yin was 45%, highlighting the importance of early treatment.

Asbestos workers suffering from malignant pleural mesothelioma have an average survival time of only 11.4 months from the onset of symptoms to death, with most patients dying within a year. The next step should be to more scientifically integrate various treatment measures while developing new technologies to identify more effective drugs and diagnostic methods for early treatment.