| disease | Sinus Trauma |

Based on anatomical characteristics, maxillary sinus injuries are the most common in both peacetime and wartime, followed by frontal sinus injuries, while ethmoid sinus injuries are less frequent, and sphenoid sinus injuries are the rarest. Nasal sinus trauma often involves concurrent injuries to the cranium and orbits, frequently accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Depending on the nature of the injurious factors and the direction of violence, the clinical manifestations vary, primarily involving hemorrhage, deformity, functional impairment, and infection.

1. Hemorrhage

Grade I hemorrhage results from mucosal tears or rupture of small blood vessels in soft tissues. In cases of maxillary sinus or ethmoid sinus trauma, as well as injuries to larger vessels such as the maxillary artery, sphenopalatine artery, anterior or posterior ethmoid arteries, or the pterygoid venous plexus, bleeding may be difficult to control and can lead to shock. If the sphenoid sinus is injured along with rupture of the cavernous sinus or internal carotid artery, the hemorrhage can be severe and rapidly fatal. In ethmoid and frontal sinus injuries, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea may occur, mixed with blood, making early differentiation challenging and requiring prompt attention.

2. Deformity

Facial collapse is seen in comminuted fractures of the frontal sinus or the anterior part of the maxillary sinus. Enophthalmos occurs in orbital floor blowout fractures, where orbital soft tissues prolapse into the maxillary sinus. Lateral displacement of the eyeball may result from fractures of the ethmoid sinus lamina papyracea and local hematoma compression. Deformity of the upper alveolar ridge can arise from transverse fractures of the maxillary sinus. When hematoma, emphysema, or tissue edema is present in the maxillofacial region, accurate assessment of sinus wall deformities may be difficult. Plain X-rays, tomography, or CT scans can aid in diagnosis.

3. Functional ImpairmentOlfactory dysfunction may result from ethmoid or frontal sinus injuries extending to the anterior cranial fossa floor. Visual impairment or diplopia often stems from trauma to the ethmoid or sphenoid sinuses affecting the orbital apex or intraorbital structures, or from orbital floor blowout fractures. Trismus may occur if maxillary sinus trauma involves the pterygopalatine fossa muscles. Malocclusion arises in cases of alveolar ridge fractures and deformities. Nasal obstruction can be caused by post-traumatic nasal stenosis, mucosal swelling, or scar adhesions following sinus injury. Sphenoid sinus fractures involving the sella turcica may also lead to traumatic diabetes insipidus.

4. Infection

Following sinus fractures, infection can spread from the sinus cavity to soft tissues even in the absence of open wounds. If open wounds are present, contaminants such as dirt or debris may enter the sinus cavity, leading to infection. Retained foreign bodies or sequestra can result in persistent purulent fistulas.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

1. Hemostasis

Progressive bleeding is generally controlled by packing. However, if bleeding is accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, packing should be avoided to prevent intracranial infection. Ephedrine or adrenaline-soaked cotton pads can be used for hemostasis. If bleeding persists, external carotid artery ligation or anterior/posterior ethmoidal artery ligation may be performed. For primary or secondary torrential bleeding, emergency bilateral external carotid artery ligation can be performed, supplemented by bilateral anterior and posterior nasal packing if necessary, which often leads to successful resuscitation. During hemostasis, care should be taken to prevent blood aspiration into the trachea, and a head-low, foot-high position may be adopted if needed.

2. DebridementDebridement should be performed promptly, ideally within 24 hours, to prevent infection and minimize scar formation. Principles of debridement: ① Preserve soft tissue and bone structures that provide essential support; ② Remove traumatized bone walls that may obstruct sinus drainage into the nasal cavity.

Principles for managing foreign bodies: ① Remove easily accessible foreign bodies immediately; ② For those posing risks during removal but also causing severe consequences if left, prepare adequately before extraction (e.g., sharp small objects embedded in vascular plexuses or infected materials embedded in the cerebral membrane); ③ For foreign bodies posing removal risks but no significant harm if left, they may be retained (e.g., air gun pellets deeply embedded in the skull base without functional impairment or infection risk).

3. Reduction

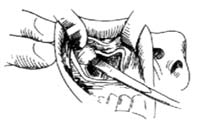

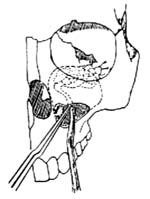

Principles of reduction: ① Linear fractures without cosmetic or functional impairment require no intervention; ② Fractures causing facial collapse or affecting eye/nasal function should undergo open reduction. Via standard sinus surgical approaches, depressed bone fragments can be elevated and fixed with iodoform gauze packing for 3–5 days (Figures 1 and 2); ③ Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea should be repaired using temporalis fascia grafts; ④ After reduction, create a wide drainage opening from the sinus to the nasal cavity, with one end of the iodoform gauze exiting through this opening; ⑤ Pack the nasal cavity with Vaseline gauze and place a ventilation tube to prevent nasal meatus stenosis or adhesions; ⑥ For large facial defects, suture the wound edges to the sinus mucosal membrane to close the wound, facilitating intermediate-stage [second-stage] reconstruction.

Figure 1 Reduction of zygomatic fracture via the maxillary sinus approach

Figure 2 Reduction method for fracture of the maxillary sinus roof