| disease | Fracture of the Axis Vertebral Body |

Reports of axis body fractures are relatively rare. In fact, this type of injury is not uncommon but is scattered among reports of Hangman fractures and odontoid fractures. Some atypical Hangman fractures reported in the literature are actually axis body fractures, while Anderson-D'Alonzo type III odontoid fractures, by definition, represent axis body fractures rather than true odontoid fractures.

bubble_chart Pathogenesis

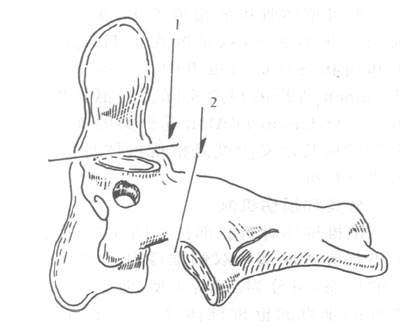

The site of the axis vertebral body fracture is shown in Figure 1, located between the base of the dens and the bilateral pedicles. According to the morphology of the fracture, it can be divided into three types: Type I: The fracture line is vertically arranged in a coronal plane. The mechanisms include: (1) Slightly less extension than the force causing a Hangman fracture, combined with a small axial load, leading to a vertical fracture in the dorsal part of the axis vertebral body. (2) A primary axial compression load with extension force applied to the frontoparietal region, causing a vertical fracture in the dorsal part of the vertebral body, along with anterior rupture of the C23 intervertebral disc, avulsion fracture of the anteroinferior edge of the C2 vertebral body, and hyperextension of most of the C1 and C2 vertebral bodies. (3) Flexion force combined with axial load applied to the occipitoparietal region, resulting in a vertical dorsal fracture of the C2 vertebral body, disc rupture, anterior displacement of the C2 complex (the atlas and most of the axis vertebral body), and tearing of the anterior longitudinal ligament. (4) Flexion combined with distraction force may cause a posterior fracture of the axis vertebral body, partial disc rupture, and flexion of the C2

complex. (5) Acute hyperextension and rotational force, as Schneider et al. briefly described a similar fracture caused by a noose knot placed below the ear. Type II: The fracture line is vertically oriented in a sagittal plane, i.e., a fracture of the lateral mass or superior articular process of the axis. The injury mechanism involves axial compression and lateral bending forces transmitted through the occipital condyle to the lateral mass of the atlas and then to the lateral mass of the axis, causing a compressive fracture. Type III: The fracture line is horizontally oriented in the axis vertebral body, i.e., a Type III dens fracture, which will not be elaborated here.

Figure 1: Range of axis fractures

1. Dens fracture; 2. Hangman fracture

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of axis vertebral body fractures vary depending on the type of fracture. Patients with type I fractures have a higher probability of accompanying neurological damage. Due to the anterior portion of the axis vertebral body displacing forward along with the atlas, while the posterior fracture fragments remain in place, there is a risk of spinal cord compression. However, there are also reports of patients with intact neurological function presenting only with severe neck pain. Patients with type II fractures generally do not exhibit neurological symptoms, experiencing only local symptoms such as neck pain and stiffness.

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

In conventional X-ray examinations, lateral cervical spine radiographs and sagittal tomograms are highly useful for diagnosing Type I fractures. The lateral view can reveal the fracture line passing through the dorsal aspect of the axis vertebral body, with the majority of the anterior portion of the vertebral body and the atlas displaced forward, accompanied by flexion or extension angulation deformities. Meanwhile, the posterior and inferior portions of the vertebral body remain in their original position, normally located above the C3

vertebral body. Tomograms can clearly display the fracture line and the displacement of fracture fragments. Open-mouth views and coronal tomograms are particularly valuable for diagnosing Type II fractures, as they can show the collapse of the lateral mass of the axis and the intrusion of the lateral mass of the atlas into the superior articular surface of the axis. Type III fractures are discussed in Section 1 of this chapter.CT, especially three-dimensional CT reconstruction, is crucial for obtaining comprehensive information about the fracture. MRI's excellent soft tissue resolution makes it widely used for spinal cord injuries. Similarly, in patients with axis vertebral body fractures, MRI can clearly reveal spinal cord injuries and compression.

The diagnosis should be based on accurate and detailed medical history, physical examination, and a comprehensive analysis of various imaging results to determine the point of violent impact, injury mechanism, and obtain complete information about the C2 vertebral fracture as well as the condition of surrounding bones and soft tissue injuries.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The treatment of axis vertebral body fractures should still primarily focus on conservative management, tailored to each patient's unique injury mechanism. For patients without neurological damage or significant displacement, gypsum fixation is applied. For those with displacement, traction reduction is performed, with precautions as outlined in Section 2. For injuries caused by flexion and distraction forces, traction may worsen displacement or lead to overdistraction. In such cases, Halo brace fixation should be used instead, with slight compression under imaging guidance. Patients with neurological deficits may initially undergo traction reduction under close observation, supplemented by various imaging studies to assess fracture displacement and spinal cord compression. If reduction is achieved and symptoms improve, traction can be continued. If symptoms do not improve or progress stalls, the surgical approach and technique should be selected based on imaging findings indicating the site of spinal cord compression. For irreducible Type II fractures, posterior fusion surgery may be considered to prevent long-term instability, malunion, or degenerative atlantoaxial arthritis.