| disease | Dental Caries |

| alias | Caries,Dental Caries, Tooth Decay |

Dental caries is a progressive sexually transmitted disease caused by multiple factors in the oral cavity, leading to the demineralization of inorganic substances and the decomposition of organic matter in tooth hard tissues. It manifests as a color change and eventually forms a substantial sexually transmitted disease lesion. Characterized by high prevalence and widespread distribution, the average caries incidence rate is around 50%. It is a major common oral disease and one of the most prevalent diseases in humans. The World Health Organization has classified it alongside cancer and heart blood vessel diseases as one of the three major diseases requiring focused prevention and treatment in humans.

bubble_chart Etiology

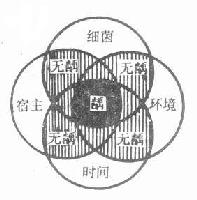

The currently recognized theory of the cause of dental caries is the four-factor theory (Figure 1), which primarily includes bacteria, oral environment, host, and time. The key points are as follows: Cariogenic foods (especially sucrose and refined carbohydrates) adhere tightly to the tooth surface, forming an acquired membrane composed of salivary proteins. This membrane, shaped by the tooth's surface anatomy, generation and transformation, and biophysical characteristics, not only firmly attaches to the tooth surface but also allows sufficient time under suitable temperatures for acid production in the deep layers of plaque, eroding the teeth, leading to demineralization, and subsequently destroying organic matter, resulting in cavities.

Figure 1: Diagram of the Four-Factor Theory

1. Bacteria

Bacteria are a necessary condition for the occurrence of dental caries. It is generally believed that there are two types of cariogenic bacteria: one is acid-producing bacteria, primarily Streptococcus mutans, Actinomyces, and Lactobacillus, which can break down carbohydrates to produce acid, leading to demineralization of the tooth's inorganic matter; the other is Gram-positive cocci, which can destroy organic matter and, over time, form cavities in the teeth. The most widely recognized primary cariogenic bacteria are Streptococcus mutans, with others including Actinomyces and Lactobacillus.

Bacteria primarily adhere to the tooth surface via plaque. When carbohydrates from retained food in the mouth are degraded, they polymerize to produce highly viscous glucans, forming the plaque matrix, while also producing acid that demineralizes the teeth. Plaque composition is complex, containing not only large quantities of bacteria but also sugars, proteins, enzymes, and other substances.2. Oral Environment

The oral cavity is the external environment of the teeth and is closely related to the occurrence of dental caries, with food and saliva playing dominant roles.

(1) Food mainly consists of carbohydrates, which are involved in the formation of the plaque matrix and serve as the primary energy source for plaque bacteria. Bacteria metabolize carbohydrates (especially sucrose) to produce acid and synthesize extracellular and intracellular polysaccharides. The organic acids produced favor the growth of acid-producing and acid-tolerant bacteria and contribute to the demineralization of dental hard tissues. Polysaccharides promote bacterial adhesion and abdominal mass on the tooth surface and provide an energy source when exogenous sugars are lacking. Thus, carbohydrates are the material basis for dental caries.

(2) Saliva normally performs the following functions:

Mechanical cleaning reduces bacterial abdominal mass.

Antibacterial effects directly inhibit bacteria or their adhesion to the tooth surface.

Acid-neutralizing effects are achieved through substances like bicarbonates.

Anti-dissolution effects enhance the tooth's acid resistance and reduce solubility via calcium, phosphorus, fluoride, and other components.

Changes in the quantity or quality of saliva can affect the caries rate. Clinically, patients with dry mouth or reduced saliva secretion exhibit a significantly higher caries rate. Patients undergoing maxillofacial radiotherapy may develop multiple caries due to salivary gland damage. Conversely, an increase in lactic acid or a decrease in bicarbonate content in saliva can also promote caries.

The tooth is the target organ in the caries process. The tooth's morphology, degree of mineralization, and tissue structure are directly related to caries susceptibility. For example, pits and fissures or poorly mineralized teeth are more prone to caries, while well-mineralized teeth with appropriate fluoride content exhibit stronger caries resistance. Additionally, tooth structure is closely related to the body, particularly during development, influencing not only tooth development and structure but also saliva flow rate, velocity, and composition, making it a critical factor in caries occurrence.

4. Time

The occurrence of dental caries is a relatively long process. It generally takes 1.5 to 2 years from the initial stage [first stage] of caries to the clinical formation of a cavity. Therefore, even if cariogenic bacteria, a suitable environment, and a susceptible host coexist, dental caries will not occur immediately. Only when these three factors persist simultaneously for a considerable period of time can caries develop. Thus, the time factor plays a significant role in the occurrence of dental caries.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

1. Predilection sites of dental caries

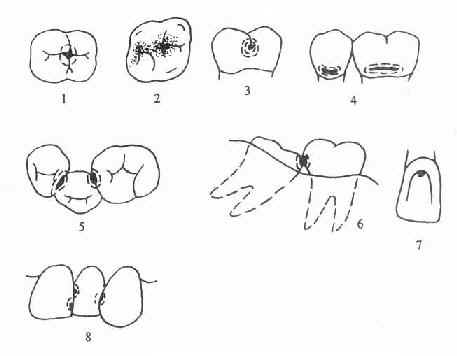

The predilection sites of dental caries are closely related to whether food is prone to retention. Areas on the tooth surface that are difficult to clean and where bacteria and food debris tend to accumulate have more plaque abdominal mass, making them prone to caries. These areas are the predilection sites of dental caries, including pits and fissures, proximal surfaces, and the cervical area of the tooth (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Predilection sites of dental caries

1.2. Occlusal pit and fissure caries in posterior teeth 3. Buccal groove caries in molars 4. Cervical caries 5. Proximal caries in posterior teeth

The pits and fissures of teeth are defects left during tooth development and mineralization, and they are also the primary sites for caries. The proximal surfaces of teeth are the second most common sites for caries, usually caused by food impaction due to wear of the proximal contact surfaces or atrophy of the interdental papilla. The cervical area is the junction between enamel and dentin, which not only facilitates the retention of food and bacteria but is also a weak point in the tooth structure. Caries is especially likely to occur when the enamel and cementum do not meet, leaving the dentin directly exposed.

2. Teeth prone to caries

Due to differences in the anatomical morphology and location of different teeth, the incidence of caries varies among teeth. Extensive epidemiological survey data indicate that the distribution of caries is roughly symmetrical between the left and right sides, more common in the mandible than the maxilla, and more frequent in posterior teeth than anterior teeth, with the lowest caries rate in mandibular anterior teeth.

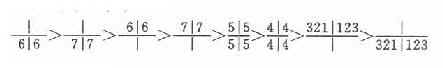

The order of caries prevalence in primary teeth is:

The order of caries prevalence in permanent teeth is:

3. Severity of caries

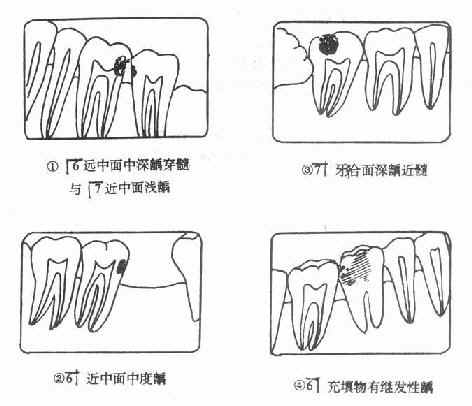

Clinically, dental caries manifests as changes in color, shape, and texture, with texture changes being the primary feature. Changes in color and shape are the results of texture changes. As the condition progresses, the lesion moves from the enamel into the dentin, and the tissue is continuously destroyed and disintegrated, gradually forming a cavity. Clinically, caries is often classified into three stages based on severity: superficial, moderate, and deep caries, each with the following manifestations (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3 Severity of caries

Superficial caries: Also known as enamel caries, the decay is confined to the enamel. In the initial stage [first stage], it appears as a chalky patch due to demineralization on smooth surfaces, later turning yellowish-brown due to staining. In pits and fissures, it appears as diffuse ink-like staining. There is usually no obvious cavity, only a rough sensation upon probing. In the late stage [third stage], a shallow cavity confined to the enamel may appear, with no subjective symptoms and no response to probing.

Moderate caries: The decay has reached the superficial layer of the dentin. Clinical examination reveals a clear cavity, and probing may cause pain. There may be a painful response to external stimuli (such as cold, heat, sweet, sour, or food impaction), but the pain disappears immediately after the stimulus is removed, with no spontaneous pain.

Deep caries: The decay has reached the deep layer of the dentin. It generally presents as a large and deep cavity or a small entrance with extensive destruction in the deeper layers. The response to external stimuli is more severe than in moderate caries, but the pain still stops immediately after the stimulus is removed, with no spontaneous pain.

Caries appears as a black radiolucent area on X-rays. For cases that are difficult to diagnose (such as proximal caries), X-rays can assist in diagnosis.

4. Types of carious lesions

(1) Chronic caries

Caries generally progresses slowly, especially in adults, and is mostly chronic. Due to the long course of the disease, the texture is relatively dry, and soft caries is less common. Such patients have a longer repair process, and the cavity floor usually has a layer of sclerotic dentin.

(2) Acute caries

It is commonly seen in children, adolescents, pregnant women, or individuals with poor health. The course of the disease is short and progresses rapidly, with a higher incidence of soft caries. The texture is loose and soft, and the discoloration is light, appearing as pale yellow or chalky white. It is easily excavated, and the cavity floor lacks a hardened dentin layer.

(3) Arrested caries

When local cariogenic factors are eliminated, leading to very slow or completely halted progression of caries, it is called arrested caries.

(4) Secondary caries

This commonly occurs when carious tissue is not completely removed during caries treatment or when the margins of restorations are not well-adapted, forming gaps that lead to recurrent caries (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Schematic diagram of various types of caries

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

1. Oral Examination

Dental caries are prone to occur in areas where teeth are not easily self-cleaned, particularly in the fissures of molar occlusal surfaces or in crowded areas of the dentition where food gets trapped. The depth of caries can be classified into three types.

1) Superficial Caries: The lesion is confined to the enamel or cementum, with localized white or gray-black spots visible. There are no subjective symptoms. The tip of a probe may get stuck during examination, and sliding the probe over the affected area feels rough, with no pain upon probing.

2) Moderate Caries: The lesion is deeper, involving the superficial layer of dentin. The area appears darkened, and there may be pain triggered by temperature or chemical stimuli. Probing reveals a distinct carious cavity with sensitivity.

3) Deep Caries: The lesion extends deep into the dentin and approaches the pulp cavity. Pain occurs when food is trapped or in response to stimuli such as hot, cold, sweet, or sour substances. A black cavity is often visible. Probing reveals the cavity floor in the deep layer of dentin, with extreme sensitivity or pain upon probing, but no history of spontaneous pain.

2. Auxiliary Examination

If it is difficult to determine the location of caries, an X-ray dental film can be taken, which will show a dark shadow at the carious site. Advanced techniques such as fiber-optic transillumination, electrical impedance, ultrasound, elastic mold separation, or staining can be employed to enhance the accuracy and sensitivity of early caries diagnosis, where conditions permit.

1. Inquire about reactions to stimuli such as cold, heat, sourness, and sweetness, as well as the presence of food impaction and spontaneous pain.

2. Examine changes in the color, shape, and texture of the tooth's hard tissues, including the location, depth, and type of caries. Pay attention to cavities on proximal surfaces, cervical areas, or areas obscured by the gums. X-ray imaging may be necessary if required.

3. Based on the severity of caries, they can be classified into: ① Superficial caries: Limited to the enamel or cementum, usually asymptomatic with no response upon probing. ② Moderate caries: Extends into the superficial layer of dentin, may cause pain in response to cold, heat, sour, or sweet stimuli, as well as probing. ③ Deep caries: Extends into the deep layer of dentin but does not reach the pulp, typically causing pain upon stimulation and probing, but no spontaneous pain.

4. Based on the pathological type of caries, they can be classified into: ① Chronic caries: Long course, with hard, dry, and deeply stained carious tissue. ② Acute caries: Short course and rapid progression, with soft, moist, and lightly stained carious tissue. If multiple teeth or even the entire dentition develop acute caries in a short time, with extensive affected surfaces and rapid deep progression, often presenting as ring-shaped at the cervical area, it is also called rampant caries. ③ Arrested caries: The cavity appears shallow and dish-shaped, with very slow or halted progression, often exposing hard, smooth, and pigmented dentin. ④ Secondary caries: Caries occurring at the margins of fillings or restorations.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The purpose of caries treatment is to halt the disease process, prevent further progression, and restore the tooth's natural form and function. Due to the unique structure of teeth, although they possess remineralization capabilities, they lack the ability to self-repair substantial defects. Except for a few cases where medication can be used, most treatments involve restorative procedures such as fillings, inlays, or artificial crowns, depending on the extent and volume of the tooth defect, to restore form and function.

1. Medication Therapy

Medication therapy involves applying drugs to inhibit caries progression after removing the decayed tissue. It is suitable for shallow caries in permanent teeth that have not yet formed cavities, as well as shallow and moderate cavities in deciduous anterior teeth. Commonly used drugs include silver ammonia solution and sodium fluoride.

Treatment method: First, remove as much decayed tissue as possible and thin the edges of the cavity to open it up. Isolate saliva with cotton rolls, dry the tooth surface, and then apply silver ammonia solution to the decayed surface with a small cotton ball for 1–2 minutes. Use a warm air gun to dry and repeat the application twice. Next, apply clove oil with a small cotton ball to reduce the solution, turning it black, and dry to complete the treatment. The resulting reduced silver precipitates in the dentinal tubules, blocking them and preventing further caries progression. This is typically performed once a week, with 3–4 sessions constituting a course. Follow-up is recommended after 3–6 months. Care should be taken to avoid burning soft tissues during treatment.

2. Amalgam Filling

For teeth with substantial defects, fillings are currently the most widely used and effective method. The process can be divided into two steps: first, remove the decayed tissue and unsupported weak tooth structure, and shape the cavity according to specific requirements. Then, fill the cavity with restorative material to restore its natural form and function. This method is suitable for posterior teeth and hidden cavities in anterior teeth.

(1) Basic Principles of Cavity Preparation

Remove all decayed tissue to prevent secondary caries. One purpose of cavity preparation is similar to debridement, requiring the removal of decayed tissue to ensure the cavity is established on healthy tooth structure and prevent secondary infection.

Protect the dental pulp. The pulp is a living tissue with sensation and metabolism. Since dentin and the pulp are closely related, cutting tooth tissue can cause varying degrees of irritation to the pulp, potentially leading to pulp hyperemia and inflammatory reactions. Therefore, care must be taken to protect the pulp and minimize irritation during the procedure.

Prepare resistance and retention forms.

Since teeth must bear masticatory forces after restoration, the filling must meet two requirements: first, it must remain stable and not loosen or fall out over time, requiring a retention form; second, both the restoration and remaining tooth structure must resist fracture under chewing forces, requiring a resistance form. Both aspects must be considered during cavity preparation.

(2) Amalgam Filling Procedure:

Remove decayed tissue and establish the cavity outline;

Prepare resistance and retention forms;

Refine the cavity shape and clean the cavity;

Disinfect the cavity;

Place a base;

Fill with amalgam;

Polish.

3. Composite Resin Filling

Suitable for anterior teeth and posterior teeth cavities not subjected to heavy chewing forces. Key points include:

① Prepare a specific cavity shape.

② For cavities of grade II or higher, a base is required.

③ Mixing tools must be clean and dry. Use a non-metal spatula, pay attention to the component ratio, and mix thoroughly.

④ Maintain dryness during filling to avoid bubbles. Use a polyester membrane or cellophane to compress the material, then shape and polish.

4. Acid-Etch Light-Cured Composite Resin Filling

Indications are the same as for composite resin fillings, and it is also suitable for teeth with extensive defects, poor retention, or discoloration. Key points include:

① Thoroughly clean the tooth surface.

② Cover exposed dentin with zinc phosphate cement or calcium hydroxide preparations.

③ Etch the tooth surface with 35% or 50% phosphoric acid for 1–2 minutes.

④Thoroughly rinse and dry the tooth surface to prevent recontamination.

⑤ Apply adhesive, fill with light-cured composite resin, then irradiate with visible light for 20-40 seconds to cure, and finally shape and polish.

5. Inlay

A restoration made of metal or other materials that fits the tooth cavity and is embedded within it is called an inlay; one that covers the occlusal surface is called an onlay. It is suitable for:

① Large cavities on the occlusal surface of posterior teeth or posterior teeth at risk of fracture.

② Proximal-occlusal cavities where filling cannot restore the proximal contact with adjacent teeth.

③ Serving as a semi-fixed bridge abutment.

The key points are:

① Completely remove carious tissue and unsupported enamel rods.

② The cavity depth should be no less than 2.5mm, with a 45° cavosurface margin bevel, and the cavity walls should diverge occlusally at an angle of less than 5°.

③ Pins or grooves may be added to assist retention.

④ For teeth with thin walls or weak cusps, full occlusal surface preparation is required.

⑤ Fabricate a model wax pattern, invest it promptly, and use direct casting whenever possible.