| disease | Endometriosis |

| alias | Pelvic Endometriosis, Endometriosis |

Normally, the endometrium covers the inner surface of the uterine cavity. If certain factors cause the endometrium to grow in other parts of the body, it can lead to endometriosis. This ectopic endometrium not only contains endometrial glands histologically but is also surrounded by endometrial stroma. Functionally, it undergoes significant changes in response to estrogen levels, varying with the menstrual cycle, though only partially influenced by progesterone. It can produce small amounts of "menstruation," leading to various clinical symptoms. If the patient becomes pregnant, the ectopic endometrium may undergo decidual-like changes. Although this ectopic endometrium grows in other tissues or organs, it differs from the infiltration of malignant tumors. The peak incidence of this condition occurs between the ages of 30 and 40. The actual incidence of endometriosis is much higher than clinically observed. For example, during exploratory laparotomy for other gynecological conditions or upon careful pathological examination of removed uterine appendage specimens, approximately 20–25% of patients are found to have ectopic endometrium.

bubble_chart Etiology

1. Implantation Theory The earliest (1921) hypothesis suggested that the occurrence of endometriosis in the pelvic cavity is due to fragments of the uterine endometrium flowing backward with menstrual blood through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity, where they implant on the ovaries or other pelvic sites. Clinically, during exploratory laparotomy performed during menstruation, menstrual blood can be found in the pelvic cavity, and uterine endometrium is detected within the blood. Endometriosis in abdominal wall scars formed after cesarean sections serves as strong evidence for the implantation theory.

2. Serous Membrane Theory Also known as the metaplasia theory, it proposes that ovarian and pelvic endometriosis arise from the metaplasia of the peritoneal mesothelial cell layer. The paramesonephric ducts develop from the inward invasion of the primitive peritoneum, and the ovarian germinal epithelium, pelvic peritoneum, and obliterated peritoneal recesses—such as the peritoneal sheath of the inguinal canal (Nuck's canal), rectovaginal septum, and umbilicus—all originate from the differentiation of coelomic epithelium. Any tissue derived from coelomic epithelium has the potential to metaplastically transform into tissue nearly indistinguishable from uterine endometrium. Thus, peritoneal mesothelial cells may, under mechanical (including tubal insufflation, retroverted uterus, cervical obstruction), inflammatory, or ectopic pregnancy stimuli, undergo metaplasia to form ectopic uterine endometrium. The germinal epithelium on the ovarian surface, being primitive coelomic epithelium, has even greater differentiation potential. Under the influence of hormones or inflammation, it can differentiate into various embryonic tissues, including uterine endometrium. The ovary is the most commonly affected site in external endometriosis, which is easily explained by the metaplasia theory. The implantation theory cannot account for the occurrence of endometriosis beyond the pelvic cavity.3. Immunological Theory In 1980, Weed et al. reported that ectopic endometrium is surrounded by infiltrating lymphocytes and plasma cells, with hemosiderin-laden macrophages and varying degrees of fibrosis. They proposed that ectopic endometrial lesions act as foreign bodies, activating the body's immune system. Subsequently, many scholars explored the disease cause and mechanism of endometriosis from the perspectives of cellular and humoral immunity.

(2) Defects in Humoral Immune Function Other theories regarding the pathogenesis of ectopic endometrial tissue include: ① Lymphatic dissemination theory: It suggests that uterine endometrium can spread via the lymphatic system. Endometrial tissue has been found in the parametrial and internal iliac lymph nodes. However, a weakness of this theory is that endometrial tissue is rarely observed in the central regions of regional lymph nodes, and the common sites of occurrence do not align with normal lymphatic drainage. ② Hematogenous dissemination theory: According to literature, ectopic uterine endometrium has been found in veins, pleura, liver parenchyma, kidneys, upper arms, and lower limbs. Some scholars believe the most likely explanation is the hematogenous spread of endometrium to these tissues and organs, and experimental endometriosis has been induced in rabbit lungs. However, others argue that while hematogenous spread may explain these cases, the role of local metaplasia cannot be ruled out, as the pleura also originates from coelomic epithelium. During embryonic development, coelomic epithelium might ectopically migrate during the formation of germ layers and mesonephric ducts, later undergoing metaplasia to form endometriosis in these locations.

Regardless of the origin of the ectopic uterine membrane, its growth is related to ovarian endocrine function. Clinical data can illustrate this, as the condition mostly occurs in women of reproductive age (30-50 years old account for over 80%) and is often complicated by ovarian dysfunction. After ovarian removal, the ectopic membrane atrophies. The growth of ectopic uterine membrane primarily depends on estrogen. During pregnancy, when progesterone secretion increases, the ectopic membrane is suppressed. Long-term oral administration of synthetic progestins such as norethindrone, which induces pseudocyesis, can also cause the ectopic membrane to atrophy.

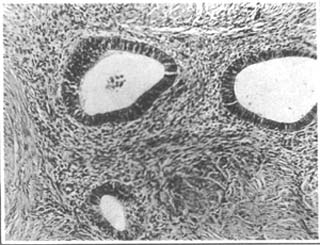

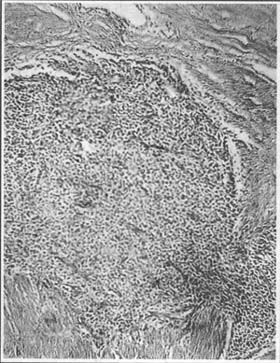

1. Internal Uterine Endometriosis The endometrium grows from the basal layer into the myometrium, confined to the uterus, hence also known as adenomyosis. The ectopic endometrium often diffusely infiltrates the entire uterine wall. The invasion of the endometrium induces reactive hyperplasia of fibrous tissue and muscle fibers, causing uniform enlargement of the uterus, though rarely exceeding the size of a full-term fetal head. Uneven or focal distribution is more commonly observed in the posterior wall. When localized to a part of the uterus, it often leads to irregular uterine enlargement, resembling a uterine fibroid. The cross-section reveals proliferative muscle tissue with a whorl-like structure similar to fibroids, but lacks the encapsulating membrane-like tissue that separates fibroids from surrounding normal muscle fibers (Photo 1). Softened areas may be present within the lesion, occasionally with scattered small cavities containing small amounts of old blood. Microscopically, the endometrial glands resemble those of the uterine endometrium, surrounded by endometrial stroma (Photo 2). The ectopic endometrium changes with the menstrual cycle, but secretory phase changes are less pronounced, indicating that the ectopic endometrial glands are less influenced by progesterone. During pregnancy, the stromal cells of the ectopic endometrium may exhibit significant decidual-like changes, as mentioned above.

Photo 1: Diffuse Uterine Adenomyosis

Photo 2: Histological Appearance of Uterine Adenomyosis

2. Stromal Uterine Endometriosis A rare subtype of internal uterine endometriosis, where the ectopic endometrium consists solely of stromal tissue, or the stromal tissue develops far more extensively and severely than the glandular components after endometrial invasion into the myometrium (Photo 3). The uterus is generally uniformly enlarged, with ectopic cells scattered throughout the myometrium or concentrated in a specific area, appearing yellow and often rubbery in consistency, softer than fibroids. The cross-section may reveal cord-like, worm-like protrusions, which can aid in diagnosis. The ectopic tissue may also extend into the uterine cavity, forming polypoid masses—multiple, smooth-surfaced, with broad stalks directly connected to the uterine wall. These may protrude into the uterine cavity or extend along uterine vessels into the broad ligament. Protrusion into the uterine cavity can cause hypermenorrhea or even postmenopausal bleeding, while protrusion into the broad ligament may be detected via bimanual pelvic examination. Stromal uterine endometriosis can metastasize to the lungs, even years after hysterectomy. Due to this characteristic, some consider it a low-grade malignant fleshy tumor.

Photo 3: Histological Appearance of Stromal Uterine Endometriosis

3. External Uterine Endometriosis The endometrium invades tissues or organs outside the uterus (including ectopic endometrium that spreads from the pelvis to the uterine serosa), often involving multiple organs or tissues.

The ovaries are the most common site of external uterine endometriosis, accounting for 80% of cases, followed by the peritoneal lining of the rectouterine pouch, including the uterosacral ligaments, the anterior wall of the rectouterine pouch (corresponding to the posterior vaginal fornix), and the posterior cervical wall (corresponding to the internal cervical os). Occasionally, ectopic endometrium invades the anterior rectal wall, causing dense adhesions between the bowel, posterior uterine wall, and ovaries, making surgical separation difficult. External uterine endometriosis may also invade the rectovaginal septum, forming scattered dark purple spots on the vaginal fornix mucosa or even cauliflower-like protrusions resembling carcinoma, which can only be confirmed as endometriosis via biopsy. Additionally, as previously mentioned, ectopic endometrium may grow in the fallopian tubes, cervix, vulva, appendix, umbilicus, abdominal wall incisions, hernia sacs, bladder, lymph nodes, and even the pleura, pericardium, upper limbs, thighs, and skin.

Endometriosis in the rectouterine pouch can involve the endometrial membrane within the uterus and may also form purplish-black hemorrhagic spots or small blood-filled cysts on the peritoneal membrane, embedded within dense fibrous adhesions. Microscopic examination reveals typical endometrial tissue. The ectopic endometrial tissue in this area can further extend into the rectovaginal septum and uterosacral ligaments, forming tender, firm nodules. Alternatively, it may penetrate the posterior vaginal fornix mucosa, forming blue-purple papillary masses that develop numerous small bleeding spots during menstruation. If the anterior rectal wall is affected, menstrual-related bowel pain may occur. In some cases, endometrial lesions may encircle the rectum, forming a stricture ring that closely resembles carcinoma. Intestinal involvement accounts for approximately 10% of endometriosis cases. The lesions are typically located in the serosa and muscular layers, with rare mucosal invasion leading to ulceration. Occasionally, the formation of masses in the intestinal wall, fibrous strictures, or adhesions may cause excessive bowel kinking, leading to intestinal obstruction. Additionally, irritative symptoms such as intermittent diarrhea may occur, often worsening during menstruation.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms and signs of uterine membrane ectopic disease vary depending on the location of the ectopic membrane and are closely related to the menstrual cycle.

1. Symptoms

(1) Dysmenorrhea: A common and prominent symptom, often secondary, meaning that since the onset of membrane ectopia, patients report no pain during previous menstrual cycles but begin to experience dysmenorrhea at a certain point. It can occur before, during, or after menstruation. Some cases of dysmenorrhea are severe and unbearable, requiring bed rest or medication for pain relief. The pain often worsens with the menstrual cycle. Due to continuously rising estrogen levels, the ectopic uterine membrane proliferates and swells. If further influenced by progesterone, bleeding occurs, stimulating local tissues and causing pain. In cases of intrinsic uterine membrane ectopia, uterine muscle spasms may be induced, making dysmenorrhea even more pronounced. In cases where ectopic tissues do not bleed, dysmenorrhea may be caused by vascular congestion. After menstruation, the ectopic membrane gradually atrophies, and dysmenorrhea disappears. Additionally, in pelvic uterine membrane ectopia, many inflammatory processes can be detected. It is likely that local inflammatory processes are accompanied by active peritoneal lesions, producing prostaglandins, kinins, and other peptide substances that cause pain or tenderness.

However, the degree of pain often does not reflect the severity of the disease as observed during laparoscopy. Clinically, about 25% of patients with significant uterine membrane ectopia do not experience dysmenorrhea.

A woman's psychological state can also influence pain perception.

(2) Hypermenorrhea: In intrinsic uterine membrane ectopia, menstrual flow often increases, and menstruation is prolonged. This may be due to increased membrane, but it is often accompanied by ovarian dysfunction.

(3) Infertility: Patients with uterine membrane ectopia often experience infertility. According to reports from Tianjin and Shanghai, primary infertility accounts for 41.5–43.3%, while secondary infertility accounts for 46.6–47.3%. The causal relationship between infertility and membrane ectopia remains debated. Pelvic membrane ectopia often causes adhesions around the fallopian tubes, affecting oocyte pickup or leading to tubal blockage. Alternatively, ovarian lesions may disrupt normal ovulation, resulting in infertility. However, some argue that long-term infertility, with no cessation of menstruation, may create opportunities for uterine membrane ectopia. Once pregnancy occurs, ectopic membranes are suppressed and atrophy.

(4) Dyspareunia: This occurs in uterine membrane ectopia of the uterorectal fossa or vaginal-rectal septum, where surrounding tissue swelling affects sexual activity, with increased discomfort during the premenstrual period.

(5) Rectal tenesmus: Generally occurs before or after menstruation. Patients experience severe pain when feces pass through the rectum, with no such sensation at other times. This is a typical symptom of uterine membrane ectopia in the uterorectal fossa and nearby rectal areas. Rarely, if the ectopic membrane deeply invades the rectal mucosa, rectal bleeding may occur during menstruation. In cases where uterine membrane ectopic lesions form strictures around the rectum, tenesmus and obstruction symptoms may occur, resembling cancer.

(6) Bladder symptoms: Mostly seen in cases where uterine membrane ectopia extends to the bladder, presenting with periodic urinary frequency and dysuria. If the bladder mucosa is invaded, periodic hematuria may occur.

Uterine membrane ectopia in abdominal wall scars or the umbilicus presents as periodic local masses and pain.

Zhang Linghao reported that among 490 cases of infertility undergoing laparoscopy, 229 cases were diagnosed with endometriosis at various stages. Among these, 50 cases (21.8%) had bilateral patent fallopian tubes, 73 cases (31.7%) had one patent tube with the other partially obstructed or blocked, 72 cases (31.3%) had bilateral partial obstruction or one partially obstructed and one blocked tube, and 49 cases (21.3%) had bilateral obstruction. Bilateral tubal obstruction definitely prevents natural conception, accounting for 1/5 of endometriosis-related infertility; cases with bilateral or unilateral partial obstruction account for slightly less than 1/3; cases with bilateral patency or one patent tube make up slightly less than 1/3. Tubal obstruction or partial obstruction, as well as adhesions around the fimbriae, all hinder the entry of oocytes into the fallopian tubes. However, infertility can still occur even with one patent tube or both tubes patent. Additionally, ovarian damage caused by ectopic endometrium can impair oocyte development, ovulation, or luteal function. These changes readily explain the mechanism of infertility. The autoimmune response in endometriosis patients is also detrimental to sperm and fertilized eggs.

The rate of late abortion is also higher in patients with endometriosis. According to reports by Jones, Jones, and Naples, the late abortion rate in pregnant women with endometriosis can reach 44–47%. Naples also reported that after surgical treatment, the late abortion rate in endometriosis patients dropped to 8%.

2. Signs Patients with intrinsic uterine endometriosis often have an enlarged uterus, but it rarely exceeds the size of a 3-month pregnancy. The enlargement is usually uniform, though some areas may feel more prominent, resembling uterine fibroids. If the uterus is retroverted, it is often fixed due to adhesions. In the rectouterine pouch, uterosacral ligaments, or posterior cervical wall, one or more small, hard nodules—about the size of a mung bean or soybean—can often be palpated, usually with significant tenderness, which is more pronounced during rectal examination. This is an important diagnostic feature. Occasionally, dark purple bleeding spots or nodules may be seen in the posterior vaginal fornix. If there is extensive involvement of the rectum, a hard mass may be palpated, sometimes even misdiagnosed as rectal cancer.

Ovarian hematomas often adhere to surrounding tissues and become fixed. During bimanual gynecological examination, a tense mass with tenderness can be palpated. Combined with a history of infertility, this can easily be misdiagnosed as an adnexal inflammatory mass. If rupture occurs, internal bleeding may result, presenting as acute abdominal pain.

This disease mostly occurs in women aged 30-40. The main complaint is secondary progressive severe dysmenorrhea, which should highly suggest the possibility of endometriosis. Patients often present with infertility, hypermenorrhea, and dyspareunia. During gynecological examination, if the uterus is slightly enlarged, and nodules are palpable on the uterosacral ligaments or the posterior wall of the cervix, a diagnosis of endometriosis can be made. When endometrial cysts are present in the ovaries, bimanual examination may reveal unilateral or bilateral cystic or solid-cystic masses, usually within 10 cm in diameter, with a sense of adhesion to surrounding tissues.

Cyclical bleeding from the rectum or bladder, or pain during defecation in the menstrual period, should first raise suspicion of rectal or bladder endometriosis. If necessary, cystoscopy or proctoscopy can be performed. If ulcers are present, a tissue biopsy should be taken for pathological examination.

If there are cyclical indurations and pain in abdominal wall scars, and a history of abdominal uterine suspension, cesarean section, or uterine surgery, the diagnosis can also be confirmed.

Suspected cases that respond positively to drug therapy can also be diagnosed.

For any localized mass near the body surface, tissue should be obtained (via excision or liver biopsy needle) for pathological examination to confirm the diagnosis.

On ultrasound, the sonographic image of an endometrial cyst appears as granular, fine echoes. If the cyst fluid is viscous and contains floating endometrial fragments, it may resemble the echo characteristics of a teratoma containing fat and hair—manifesting as small, thin light bands within the fluid, distributed in parallel dotted lines. Sometimes, internal septations divide the cyst into several cavities of varying sizes, with inconsistent echoes between them. The cyst often adheres to the uterus, with indistinct boundaries. In contrast, teratomas usually have clear cyst boundaries. Ovarian endometrial cysts can also be easily confused with adnexal inflammatory masses or tubal pregnancy on ultrasound, so differentiation should be based on their respective clinical features. Additionally, using a vaginal probe to position the mass in the near field of high-frequency sound waves offers advantages in distinguishing the nature of pelvic masses, determining their origin, and guiding aspiration of cyst fluid or biopsy under ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis.

X-ray examination: Pelvic pneumography, combined pelvic pneumography and hysterosalpingography with iodized oil, or standalone hysterosalpingography can be performed. Most endometriosis patients exhibit adhesions involving the internal genitalia and intestines. Ectopic endometrium most commonly implants in the rectouterine pouch, leading to adhesions in this area and making the pouch shallower, which is particularly evident on lateral pelvic pneumography films. The fallopian tubes and ovaries may form adhesive masses, which are more clearly visualized on pneumography or contrast films. Hysterosalpingography with iodized oil may show patent or partially patent tubes. Often, 24-hour follow-up films reveal poor dispersion of iodized oil due to adhesions, appearing as small clumps or irregular, snowflake-like dots. Combining these findings with the exclusion of other causes of infertility and a history of dysmenorrhea can aid in diagnosing endometriosis.

Laparoscopy: This is an effective method for diagnosing endometriosis. Fresh implants appear as small yellow vesicles under the scope; the most biologically active lesions are large, flame-like hemorrhagic foci. Most scattered lesions coalesce into coffee-colored patches, deeply embedded. The uterosacral ligaments become thickened, sclerotic, and shortened. Scarring of the pelvic peritoneum causes the rectouterine pouch to shallow. Ovarian implants often originate from the free edge and dorsal side of the ovary, initially appearing as 1-3 mm granulomatous foci that gradually invade the ovarian cortex, forming chocolate cysts with a bluish-gray surface. These are often bilateral, adherent to each other, and tilted toward the rectouterine pouch, with extensive adhesions to the uterus, rectum, and surrounding tissues. In stages I-II, the fallopian tubes appear normal. In stages III-IV, the tubes stretch over the chocolate cysts, becoming passively elongated, edematous, and with restricted motility, though the fimbriae are usually normal, patent, or partially patent. During laparoscopy, a hysterosalpingography with dye should be performed.

1. Anti-endometrial antibody (EMAb): In 1982, Mathur used hemagglutination and indirect immunofluorescence methods to detect EMAb in the blood, cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrium of patients with endometriosis. Many scholars have reported varying numbers of cases using different methods, identifying EMAb in the blood of endometriosis patients, with a sensitivity ranging from 56% to 75% and a specificity between 90% and 100%. After treatment with danazol or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GNRHa), the serum concentration of EMAb in patients significantly decreased. Therefore, the detection of serum EMAb serves as an effective auxiliary tool for diagnosing endometriosis and monitoring treatment efficacy.

2. CA-125: In the late 1970s, Knapp and Bast first prepared the membrane antigen and antibody panel of human ovarian epithelial carcinoma cells, naming them CA-125 (antigen) and OC-125 (antibody), marking an outstanding and promising beginning for clinical molecular biology research. Barbeiri suggested that the reason for elevated CA-125 levels in endometriosis patients is due to the reflux of membrane cells from endometriosis into the pelvic cavity, followed by biochemical coelomic metaplasia through generation and transformation, leading to the production of more CA-125 antigen. Additionally, inflammation associated with endometriosis increases CA-125 antigen. This antigen frequently appears in the patient's blood, thereby generating antibodies.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Before treatment, it is essential to make a definitive diagnosis as much as possible, taking into comprehensive consideration the patient's age, fertility requirements, severity of the condition, symptoms, and the extent of the lesions.

I. Hormonal Therapy

(1) Danazol: A derivative of synthetic steroid 17α-ethinyl testosterone. Its primary action is to inhibit the production of hypothalamic GnRH, thereby reducing the synthesis and release of FSH and LH, leading to suppression of ovarian function. It can also directly inhibit the synthesis of ovarian steroid hormones or competitively bind to estrogen and progesterone receptors, resulting in atrophy of ectopic endometrium, anovulation, and amenorrhea. Danazol also exhibits grade I androgenic effects, causing symptoms such as increased hair growth, deepening of the voice, breast shrinkage, and acne. Another common side effect of Danazol is fluid retention and weight gain. It is contraindicated in patients with hypertension, heart disease, or renal insufficiency. Danazol is primarily metabolized by the liver and may cause some degree of hepatocyte damage; therefore, it is contraindicated in women with liver disease.

The usual dose is 400 mg/day, taken orally in 2–4 divided doses, starting from the onset of menstruation. Symptoms usually improve within about one month. If ineffective, the dose can be increased to 600–800 mg/day, then gradually reduced to 400 mg/day once efficacy is achieved. The treatment course is typically six months, with 90–100% of cases achieving amenorrhea.

Danazol is more effective for pelvic endometriosis but less effective for ovarian ectopic masses larger than 1 cm in diameter.

(2) Nemestran (Gestrinone, R2323): A 19-nortestosterone derivative with high anti-progestogenic activity and grade II anti-estrogenic effects. It inhibits FSH and LH secretion, reduces estrogen levels in the body, and causes atrophy and absorption of ectopic endometrium.

(3) Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists (GnRHa): In 1982, Meldtum and Lemay reported successful treatment of endometriosis using LHRHa. LHRH has a biphasic effect on the pituitary. Large, continuous doses of LHRH cause downregulation of pituitary cells, where receptors are saturated, preventing the synthesis and release of FSH and LH, leading to counter-regulation. Side effects include tidal fever, vaginal dryness, headache, and minor vaginal bleeding.

(4) Tamoxifen (TMX): A diphenylethylene derivative. The dose is 10 mg twice daily, starting on the fifth day of menstruation, with a 20-day treatment course.

(5) Synthetic Progestins: Periodic treatment with norethisterone, norethindrone, or medroxyprogesterone acetate can cause regression of ectopic endometrium. Starting from the sixth day of the menstrual cycle to the 25th day, one of these drugs is taken orally at 5–10 mg daily. The treatment duration depends on efficacy, and this method can inhibit ovulation. For patients desiring fertility, norethisterone or norethindrone 10 mg daily can be administered from the 16th to the 25th day of the menstrual cycle. This controls uterine endometriosis without affecting ovulation. Some patients experience severe side effects during treatment, such as nausea, vomiting, bloating headache, uterine colicky pain, breast pain, and excessive weight gain due to fluid retention and improved appetite. Sedatives, antiemetics, diuretics, and a low-salt diet can alleviate these symptoms.

Testosterone: Also has some efficacy for this condition. The dose should be adjusted based on the patient's tolerance. The initial dose is preferably 10 mg twice daily, starting two weeks after the menstrual cycle. This dose rarely affects the menstrual cycle or causes androgenic side effects. However, pain relief often requires continuous administration for several cycles. The dose can then be reduced for maintenance therapy before discontinuation. If pregnancy is achieved, the condition may be cured.

II. Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is the primary method for endometriosis, as it allows for a clear visualization of the lesion's extent and nature under direct observation. It is highly effective in relieving pain and improving fertility, with a short treatment course, especially for severe cases involving extensive fibrosis and tight adhesions where medication is often ineffective. For larger ovarian endometrial cysts that do not respond to drug therapy, surgery may still preserve functional ovarian tissue. Surgical approaches can be divided into three types: conservative surgery, semi-radical surgery, and radical surgery.

(1) Conservative surgery: Mainly used for young patients who desire fertility. The uterus and adnexa are preserved (bilateral preservation is preferred as much as possible), with only the removal of lesions, separation of adhesions, reconstruction of the ovaries, and repair of tissues. In recent years, microsurgery has been applied to excise ectopic lesions, meticulously suture wounds, reconstruct the pelvic peritoneum, achieve thorough hemostasis, and perform complete irrigation, thereby optimizing surgical outcomes, improving postoperative pregnancy success rates, and reducing recurrence rates.

1. Laparoscopic surgery: Through laparoscopy, a definitive diagnosis can be made, and specialized instruments such as knives, scissors, and forceps can be used to excise lesions and separate adhesions. Under laparoscopy, CO2 lasers or helium-neon lasers can be employed to cauterize lesions. A second incision is made 2 cm above the pubic symphysis, and the laser knife is introduced into the pelvis through a cannula in this incision to cauterize lesions under direct laparoscopic visualization. Alternatively, cyst fluid can be aspirated via laparoscopic puncture, followed by irrigation with saline. Then, 5–10 ml of absolute ethanol is injected, left in place for 5–10 minutes, aspirated, and finally flushed with saline before aspiration.

Tubal patency tests can also be performed under laparoscopy.

2. Ultrasound-guided puncture of ovarian endometrial cysts: For cases of recurrence after surgical stripping or laparoscopic puncture, ultrasound-guided puncture and drug therapy may be considered.

3. Laparotomy for conservative surgery: Used for patients with severe adhesions, especially in medical institutions lacking laparoscopic equipment or where laparoscopic proficiency is insufficient. Laparotomy can be performed to separate adhesions, excise ovarian and uterine endometrial cysts, and preserve as much normal ovarian tissue as possible. If the lesion is confined to one side and is severe while the other side is normal, some advocate for the removal of the affected adnexa. This approach results in a higher pregnancy rate compared to preserving the affected ovary. A simple uterine suspension may also be performed. The necessity of presacral neurectomy remains debatable.

One of the key objectives of conservative surgery is to achieve full-term pregnancy and childbirth. Therefore, a thorough infertility evaluation of both partners should be conducted preoperatively. For postoperative recurrences, conservative surgery can be repeated, and efficacy can still be achieved.

(2) Semi-radical surgery: For patients without fertility requirements, severe lesions, and younger age (<45 years), total excision of the uterus and lesions may be performed, but efforts should be made to preserve at least one normal ovarian tissue to avoid premature menopausal symptoms. Semi-radical surgery is generally associated with a low recurrence rate and fewer sequelae. Removing the uterus eliminates the source of viable endometrial cell implantation, thereby reducing the chance of recurrence. However, recurrence is still possible if the ovaries are preserved.

(3) Radical surgery: For patients nearing menopause, especially those with severe conditions or prior recurrences, total hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy should be performed. During surgery, every effort should be made to avoid rupture of endometrial cysts. If cyst fluid leaks, it should be aspirated and irrigated promptly. For postoperative menopausal syndrome, sedatives or nilestriol may be used.

For endometrial ectopic lesions occurring in abdominal wall or perineal incisions, complete excision is necessary to prevent recurrence.

Patients with endometrial ectopic disease often have concurrent ovulatory dysfunction. Therefore, whether treated with hormone therapy or conservative surgery, HMG and/or clomiphene can be used to promote follicular maturation and ovulation.

For patients undergoing conservative surgery for infertility, hormone therapy may be administered for 3–6 months to consolidate efficacy. However, some argue that the first year post-surgery is the most likely time for pregnancy to occur, and treatment with danazol or pseudopregnancy may reduce conception chances and is therefore not recommended.

3. Radiation therapy

Although radiotherapy has been used for many years in the treatment of endometriosis, the application of various drugs and surgeries has achieved high efficacy without generally damaging ovarian function. The role of radiotherapy in treating endometriosis lies in destroying ovarian tissue, thereby eliminating the influence of ovarian hormones and causing the ectopic endometrium to atrophy, achieving the therapeutic goal. The destructive effect of radiation on ectopic endometrium is not significant. However, for individual patients who cannot tolerate hormonal therapy and whose lesions are located in the intestines, urinary tract, or extensive pelvic adhesions—especially those with severe concurrent conditions such as heart, lung, or kidney diseases—and who are extremely fearful of surgery, external radiotherapy may also be employed to destroy ovarian function and achieve therapeutic purposes. Even for those few who undergo radiotherapy, a definitive diagnosis must first be established. In particular, malignant ovarian tumors must not be misdiagnosed as endometrial cysts, leading to incorrect treatment and delaying proper therapy.

According to the currently recognized disease causes, pay attention to the following points, which may prevent the occurrence of endometriosis.

1. Avoid unnecessary, repeated, or overly rough gynecological bimanual examinations near the menstrual period to prevent squeezing endometrial tissue into the fallopian tubes, leading to peritoneal implantation.

2. Gynecological surgeries should, as much as possible, avoid being performed close to the menstrual period. If necessary, the procedure should be performed gently to avoid forcefully compressing the uterine body, which could push endometrial tissue into the fallopian tubes or peritoneal cavity.

3. Promptly correct excessive uterine retroversion and cervical stenosis to ensure smooth menstrual flow and avoid stagnation, which may cause retrograde flow.

4. Strictly adhere to the operational protocols for fallopian tube patency tests (such as insufflation or hydrotubation) and hysterosalpingography. These procedures should not be performed immediately after menstruation or during the same cycle as uterine curettage to prevent endometrial fragments from being pushed into the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes.

5. During cesarean sections or hysterotomy procedures, care should be taken to prevent uterine contents from spilling into the peritoneal cavity. When suturing the uterine incision, ensure the suture does not pass through the endometrial layer. Before closing the abdominal wall incision, rinse with saline to prevent endometrial implantation.

Since the causes are multifaceted, the above preventive measures are only applicable to a few cases. Whether retrograde menstrual flow itself causes endometriosis remains controversial.

1. Uterine Myoma Uterine myomas often present with similar symptoms. Generally, endometriosis is associated with more severe dysmenorrhea, which is secondary and progressive. The uterus is uniformly enlarged but not significantly. If endometriosis occurs in other locations, it may aid in differentiation. For cases where diagnosis is particularly challenging, a trial of medication can be attempted. If symptoms improve rapidly (within 1–2 months of treatment), the diagnosis is more likely to be endometriosis. It should be noted that adenomyosis can coexist with uterine myomas (approximately 10%). Preoperative differentiation is usually difficult and often requires pathological examination of the surgically removed uterus.

2. Adnexitis Ovarian endometriosis is often misdiagnosed as adnexal inflammation. Both conditions can form fixed, tender masses in the pelvis. However, patients with endometriosis have no history of acute infection and typically show no response to various anti-inflammatory treatments. A detailed history should be taken regarding the onset and severity of dysmenorrhea. In such cases, endometriotic nodules are often found in the rectouterine pouch, which can be detected upon careful examination and aid in diagnosis. If necessary, a trial of medication can be used to observe therapeutic response for differentiation. In ovarian endometriosis, the fallopian tubes are usually patent. Therefore, a tubal patency test can be attempted; if the tubes are patent, salpingitis can be ruled out.

3. Malignant Tumor of the Ovary Misdiagnosing ovarian cancer as ovarian endometriosis delays treatment and must be approached cautiously. Ovarian cancer does not necessarily present with abdominal pain, but if it does, the pain is usually persistent rather than cyclical, as seen in endometriosis. On examination, ovarian cancer feels solid, with an irregular surface and larger volume. Ovarian endometriosis may also coexist with endometriosis in other locations, presenting with signs of those lesions. For cases where differentiation is difficult, older patients should undergo exploratory laparotomy, while younger patients may be treated for endometriosis for a short period to observe therapeutic response.

4. Rectal Cancer When endometriosis extensively involves the rectum or sigmoid colon, it often forms a hard mass, causing partial obstruction. In rare cases, ectopic endometrial tissue invading the intestinal mucosa may cause bleeding, further mimicking rectal cancer. However, the incidence of rectal cancer is much higher than that of intestinal endometriosis. Generally, patients with rectal cancer exhibit significant weight loss, frequent intestinal bleeding unrelated to menstruation, and no dysmenorrhea. On rectal examination, the tumor is fixed to the intestinal wall, with circumferential narrowing. Barium enema reveals an irregular mucosa with a small area of poor filling. Sigmoidoscopy shows ulcers and bleeding, and biopsy confirms the diagnosis. In intestinal endometriosis, weight loss is absent, intestinal bleeding is rare (if present, it occurs during menstruation), and dysmenorrhea is severe. On rectal examination, the mucosa is not adherent to the underlying mass, and only the anterior wall feels hardened. Barium enema shows a smooth mucosa with a large area of poor filling.