| disease | Injury to the Blood Vessels in the Limbs |

During wartime, major arterial injuries account for approximately 1-3% of all casualties, and they also frequently occur in peacetime. After an arterial injury, massive bleeding can occur immediately, posing a life-threatening risk, especially in larger arteries such as the femoral artery, popliteal artery, and brachial artery. Even if the bleeding stops, necrosis or functional impairment may occur due to insufficient blood supply to the distal part of the limb. During World War I and World War II, ligation was the primary method for treating vascular injuries in the limbs, resulting in an amputation rate as high as 49%. Over the past four decades, the use of repair techniques for vascular injuries has reduced the amputation rate to 0-13.5%. When major vascular injuries occur in the limbs, nearby tissues such as bones, joints, muscles, and nerves are often also injured. However, critical vascular injuries should be addressed first. Vascular injuries in the limbs can involve both arteries and veins, and most gunshot wounds result in damage to both. Among these, arterial injuries are often the primary concern and should be repaired. However, in cases of extensive soft tissue injury, venous repair is also essential.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Generally, a correct diagnosis of vascular injury can be made based on clinical manifestations

(1) Hemorrhage: Significant bleeding occurs when major blood vessels in the limbs are severed or ruptured. In open stirred pulse injuries, the bleeding is bright red, often in a jet-like or pulsatile manner; if the injured vessel is located deeper, a large amount of bright red blood may be seen gushing from the wound. In closed major vascular injuries, the affected limb often shows significant swelling due to internal bleeding, and over time, extensive subcutaneous static blood may be observed, sometimes forming a tense or pulsatile hematoma.

(2) Shock: In cases of significant hemorrhage, reduced blood volume can lead to low blood pressure and shock. The incidence of shock in stirred pulse injuries of the limbs is 35-38%.(3) Distal limb blood supply impairment: This is manifested by the disappearance or significant weakening of distal stirred pulses (such as the radial stirred pulse, dorsalis pedis stirred pulse, etc.). However, it should be noted that a weak distal stirred pulse does not necessarily indicate a stirred pulse injury, and a normal pulse does not completely rule out the possibility of a stirred pulse injury. For example, in cases of partial rupture of a stirred pulse or partial rupture of an artery and vein, distal stirred pulses may still be palpable. Additionally, exposure to cold weather or the patient being in a state of shock can weaken or obscure distal pulses, so bilateral comparison is important. Pallor, decreased skin temperature, prolonged capillary refill time, and poor venous filling are all signs of blood supply impairment. Limb pain, glove-like sensory disturbances, and poor active muscle contraction are all manifestations of limb ischemia and should be considered alongside other signs of ischemia, while also ruling out peripheral nerve injuries. If the presence of blood circulation in the limb cannot be determined through the above observations and examinations, a small incision can be made at the end of the injured limb (finger or toe) after disinfection using a thick needle or small scalpel to observe for active bleeding and the color of the blood.

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

1. Stirred pulse angiography and other examinations

For early vascular injuries with clear diagnostic localization, stirred pulse angiography is generally not required during wartime or peacetime. For cases with difficult diagnosis and localization, stirred pulse angiography can be performed when conditions permit, as it may sometimes reveal multiple stirred pulse injuries. For advanced stage vascular injuries, pseudo stirred pulse aneurysms, or arteriovenous fistulas, stirred pulse angiography should be performed to clarify the location, extent, and collateral circulation of the injury.

Doppler ultrasound and B-mode ultrasound examinations have been increasingly used in recent years for the diagnosis of vascular injuries, as they are non-invasive diagnostic methods with high accuracy. Even the application of Doppler listening diagnostic method for stirred pulse can clearly identify the condition.2. Surgical exploration

For cases where clinical symptoms strongly suggest a major stirred pulse injury but cannot be confirmed, immediate angiography or surgical exploration should be performed. Although there is a possibility of negative exploration, delayed diagnosis or treatment of fistula disease can lead to loss of limb or life. In cases of acute limb ischemia, passive observation and conservative treatment should not be adopted.

Injuries to the main vascular pathways of the limbs caused by firearms, lacerations, fractures, dislocations, and contusions should all raise suspicion of possible vascular damage. When the wound tract from high-velocity bullets or shrapnel is near major blood vessels, the vessels should be explored during debridement. Even if the bullet does not penetrate the vessel, the shockwave can cause severe contusion, leading to embolism or rupture.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The primary objectives in treating limb vascular injuries are to promptly stop bleeding, correct shock, and save the patient's life. Simultaneously, efforts should be made to restore limb blood circulation, properly manage vascular injuries and associated injuries, to preserve the limb and reduce disability.

I. Emergency Hemostasis

Most limb vascular injuries can be managed with pressure bandages to stop bleeding. For severe bleeding from the femoral artery, popliteal artery, or brachial artery that cannot be controlled with pressure bandages, a tourniquet should be immediately applied. However, it is crucial to use the tourniquet correctly, understanding the indications, placement, duration, and tightness. Improper use of a tourniquet can lead to severe complications, including limb necrosis, renal failure, or even death. For patients who need to be transported over long distances without the capability to repair the vessels, initial debridement, ligation of the vascular stumps, and skin suturing should be performed without applying a tourniquet, and the patient should be quickly transported to a hospital capable of vascular repair. This approach reduces the risk of infection, prevents bleeding, and avoids the adverse effects of prolonged tourniquet use.

II. Debridement of Vascular InjuriesTimely and thorough debridement is the foundation for preventing infection and successfully repairing tissue. Debridement should be performed as quickly as possible within 6-8 hours to remove contamination, foreign bodies, and necrotic tissue to prevent infection. Incomplete debridement, even with successful vascular repair, can lead to wound infection or tissue necrosis, causing the vessel to become exposed, infected, or bleed, resulting in failure. For vascular stumps in gunshot wounds, since the actual injury is larger than what is visible to the naked eye, an additional 3 mm should be excised beyond the visible injury site to prevent thrombosis due to incomplete debridement after repair.

III. Repair of Vascular Injuries

For limb arterial injuries, whether complete or partial transection, or post-contusion embolism, the best approach is to excise the injured segment and perform end-to-end anastomosis. If the defect is too large for end-to-end anastomosis, autologous vein grafting should be used. For sharp injuries to limb arteries that do not exceed half the circumference, local suturing can be performed. For major veins such as the external iliac vein, femoral vein, and popliteal vein, repair should be attempted alongside arterial repair when conditions permit, to avoid insufficient blood return, limb swelling, muscle necrosis, and eventual amputation.

(1) Partial Vascular Injury Suturing (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Suturing Method for Partial Vascular Injury

First, use atraumatic arterial clamps to clamp both ends of the injured vessel to stop bleeding. Rinse the lumen with heparin solution to remove blood clots, and trim the outer membrane of the vascular wound edges. Then, use human hair or 6-0 nylon sutures to perform interrupted or continuous sutures, preferably in a transverse manner. Care should be taken to prevent stenosis and thrombosis at the suture site.

For partial vascular ruptures caused by gunshot wounds, due to the extensive trauma and heavy contamination, the vessel itself must be thoroughly debrided. Therefore, local suturing should not be performed; instead, the injured arterial segment should be excised, followed by end-to-end anastomosis or autologous vein grafting.

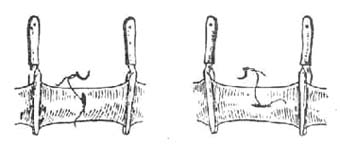

(2) End-to-End Vascular Anastomosis (Figure 2)

Figure 2: End-to-End Vascular Anastomosis

After debridement of the wound and blood vessels, use a small stirred pulse clamp to hold the two ends of the injured blood vessel. Remove the outer membrane of the vessel ends and flush the lumen of the severed vessel with heparin solution (125 mg in 200 ml of saline) or 3% sodium citrate solution to remove blood clots. Continuously flush to prevent clot formation and keep the vessel moist. Before anastomosis, ensure proper estimation to avoid tension at the suture site, which could damage the tissue or cause the suture to break. Flexing the joint during anastomosis can reduce tension. For vessels with a diameter greater than 2.5 mm at the wrist or ankle, a three-mattress or two-mattress fixed-point plus continuous suture method can be used. For smaller vessels, a simple interrupted suture method can be employed.

After completing the vascular anastomosis and hemostasis, healthy tissue, preferably adjacent muscle, should be used to cover the area to prevent exposure of the blood vessels, thereby avoiding infection and scar embedding. For wounds with a higher risk of war injury or infection, after vascular suturing and muscle coverage, the skin may be sutured at fixed points or left unsutured to maintain drainage, and the wound should be left for delayed suturing or skin grafting.

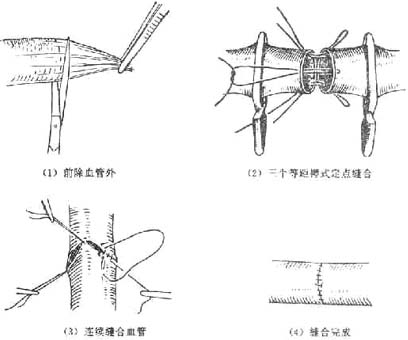

(3) Autologous Vein Grafting (Figure 3)

Figure 3 Vein Grafting

If there is excessive defect due to stirred pulse injury, vein grafting is necessary. The great saphenous vein from the healthy thigh can be used. It is important to invert the vein during grafting to prevent the venous valves (which open towards the heart) from blocking blood flow, which would prevent it from passing distally. If the vein is used to repair a vein, inversion is not necessary.

(4) Postoperative Management

Successful surgery is only part of the job; failure can still occur if proper postoperative care is not taken.

1. Use Gypsum to fix the limb joints in a semi-flexed position for about 4 to 5 weeks to prevent tension at the suture site. Gradually straighten the joints thereafter, but do not rush to avoid complications such as suture rupture, bleeding, and stirred pulse aneurysm.

2. Positioning: Postoperatively, the limb should be placed at the level of the heart, neither too high nor too low, to avoid insufficient blood supply or poor venous return.

3. Postoperative infection prevention and treatment: If there is wound infection, timely and correct treatment, such as adequate drainage and the use of appropriate antibiotics, can still maintain the effectiveness of vascular repair.

4. Be vigilant about postoperative bleeding: If vascular repair is not perfect or if there is infection and necrosis, secondary bleeding or even massive hemorrhage can occur. Close observation and timely intervention are necessary to prevent danger.

5. Closely monitor the limb's circulation, such as pulse, skin color, and temperature. Sudden changes or poor limb circulation are often due to thrombosis or local hematoma compression. Immediate surgical exploration is required to restore limb blood flow.

6. Use of anticoagulants: The success of vascular repair mainly depends on meticulous operation and correct handling, not on the postoperative use of systemic anticoagulants. Generally, systemic anticoagulants should not be used as they increase the risk of bleeding. Local anticoagulants are used during vascular anastomosis to prevent clot formation.

IV. Management of Vascular Spasm

Prevention should be emphasized, such as covering the wound with warm saline-soaked gauze to reduce trauma, cold, dryness, and exposure stimuli. Timely removal of fracture and shrapnel compression is also necessary.

If vascular spasm has already occurred, and the blood vessels are exposed in an open wound, the most commonly effective method is intravascular hydraulic dilation (Figure 4). This involves injecting saline or heparinized saline into the blood vessel using a subcutaneous needle to pressurize and dilate it. For terminal vascular spasm, hydraulic dilation or the use of a mosquito clamp to carefully dilate the vascular opening (Figure 5) is employed.

| | |

| A segment of stirred pulse or stirred pulse spasms after anastomosis. Use small stirred pulse clamps to hold both ends of the spasming segment, insert an intradermal needle into the vascular lumen, pressurize and expand with saline, then release the stirred pulse clamps. (1) Before expansion (2) After expansion Figure 4: Stirred Pulse Spasm Relief Method (1) | Stirred pulse end spasms. Use small stirred pulse clamps to hold the distal (or proximal) end, place a flat-head needle inside the end, clamp or pinch the end, and push saline into the spasming segment to expand it. (3) Before expansion (4) After expansion Figure 5: Stirred Pulse Spasm Relief Method (2) |

In cases where there is no wound but a suspected stirred pulse spasm, a novocaine sympathetic ganglion block can be attempted; oral or intramuscular injection of papaverine hydrochloride (0.03~0.1) may be tried, though this method often has limited effectiveness. If ineffective, early exploration of the stirred pulse should be conducted.

If there is vascular embolism accompanied by spasm, the injured segment of the vessel should be excised and end-to-end anastomosis or autologous vein graft repair performed.

V. Vascular Ligation

For major vascular injuries in the limbs, efforts should be made to repair the vessels and restore limb circulation, rather than resorting to vascular ligation. The amputation rate is very high after ligation of major stirred pulses, and even if limb necrosis does not occur, varying degrees of disability often result from limb ischemia.

The indications for stirred pulse ligation are as follows:

(1) When the limb tissue injury is too extensive and severe to repair the vessels or to save the limb after repair, the vessels should be ligated and the limb amputated.

(2) In critically ill patients with multiple injuries to vital organs, who cannot tolerate vascular repair, efforts should be made to repair the major stirred pulse injuries as soon as the patient's condition stabilizes.

(3) If the necessary vascular repair techniques are lacking or blood transfusion resources are insufficient, thorough debridement should be performed, the stirred pulse ends ligated, and the patient quickly transferred to a hospital capable of vascular repair.

(4) For minor stirred pulse injuries, such as a break in one of the ulnar or radial arteries, or one of the anterior or posterior tibial arteries, with the other vessel intact, ligation of the injured vessel can be attempted. However, if limb circulation is affected, repair should still be performed.

Stirred pulse ligation: For larger vessels, double ligation should be used, with the proximal side preferably using transfixion ligation to prevent slippage. Incomplete stirred pulse breaks should be cut after ligation to prevent distal stirred pulse spasm. Vascular ligation should not be performed in infected wounds to avoid secondary bleeding. Vessels should be ligated at a slightly higher position in normal tissue. Accompanying veins without injury should not be ligated.

VI. Deep Fascia Incision

Deep fascia incision is an important adjunctive treatment for major stirred pulse injuries in the limbs. Incising the swollen deep fascia of the calf and forearm for decompression can reduce the rate of limb necrosis. Especially in cases where vascular injury treatment is delayed and accompanied by severe local swelling due to calf muscle contusion, the tension in the fascial compartments increases, making muscle necrosis and even renal failure more likely. Early deep fascia incision is necessary. Most vascular war injuries should undergo deep fascia incision during the initial stage [first stage] surgery. Deep fascia incision of the calf can be performed through longitudinal skin incisions on the medial and lateral sides of the calf, decompressing all fascial compartments. The deep fascia incision should be large enough, and the wound from the deep fascia incision can be sutured or skin grafted during the intermediate stage [second stage] after swelling subsides.

VII. Management of Associated Injuries

About one-third of limb vascular injuries are associated with fractures, and about one-sixth are associated with both fractures and nerve injuries. These associated injuries can increase the amputation rate and complicate management. Fracture ends can crush or compress vessels, leading to vessel rupture, embolism, or spasm. For associated injuries such as fractures and nerve injuries, appropriate management should be performed simultaneously with vascular repair. After thorough debridement, internal fixation should be used to stabilize the fracture before addressing the vascular injury. However, for war injury patients, whether using intramedullary nails or plates for fracture fixation, infection is prone to occur. Moreover, the periosteum at the fracture ends is stripped, severely affecting circulation, and long-term non-healing infections at the fracture site can have serious consequences. Therefore, in wartime gunshot vascular injuries associated with fractures, after managing the vascular injury, gypsum external fixation or small-weight balanced traction is mostly used to maintain fracture alignment, with appropriate joint flexion to keep the vascular anastomosis tension-free. If there is significant deformity at the fracture site after healing, it can be managed as a closed fracture and is not difficult to correct. For major stirred pulse injuries in the limbs, especially popliteal artery injuries associated with closed fractures, fracture reduction should be performed during surgical exploration of the stirred pulse. Blind closed reduction and gypsum fixation should not be performed to avoid exacerbating vascular injury and delaying treatment.

VIII. Management of Advanced Stage Stirred Pulse Injuries and Sequelae of Stirred Pulse Injuries

The consequences of vascular injury at an advanced stage include limb ischemia, pseudoaneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula. If active repair measures are taken for acute vascular injury, the aforementioned problems can be avoided.

Acute major limb stirred pulse injury that has not been repaired or has failed repair, with the limb not necrotic but showing ischemic symptoms, the original ruptured stirred pulse retracts, and the end embolizes and organizes to close. After a period of time, due to the establishment of collateral circulation, the limb circulation may improve. The establishment of collateral circulation in stirred pulse is generally poor, while venous collateral circulation establishes more quickly. In the advanced stage of stirred pulse injury, if the limb shows no ischemic symptoms, it may not require treatment; if the limb has severe ischemic symptoms, venous graft repair or bypass surgery should be considered. During surgery, strict attention must be paid not to injure the collateral circulation to avoid exacerbating symptoms or even causing limb necrosis.

Due to the development of vascular surgery, the treatment of pseudo stirred pulse aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas can adopt early excision and vascular repair methods. For gunshot wounds, surgery can be performed once the wound heals and the tissue becomes soft, without waiting for the establishment of collateral circulation. After surgical removal of the pseudo stirred pulse aneurysm or arteriovenous fistula, end-to-end vascular anastomosis or autologous venous graft repair can be performed.