| disease | Cervical Spondylosis |

Cervical spondylosis is a syndrome caused by degenerative changes in the cervical intervertebral discs and cervical bone hyperplasia, leading to a series of clinical symptoms such as numbness and pain in the neck, shoulders, and upper limbs, muscle atrophy, and even paralysis of the limbs. Some individuals may experience dizziness or sudden falls. It is a disease that has only been comprehensively understood in the past 20 years.

bubble_chart Etiology

Cervical spondylosis mostly occurs in middle-aged and elderly people. According to statistics, 70% of cases occur at C5-C6, followed by C6, C4-C5, and C7-T1.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

The basic pathological changes of cervical spondylosis are the degenerative changes of the intervertebral discs. The cervical spine is located between the skull and the thorax, and the cervical intervertebral discs undergo frequent movements under weight-bearing conditions, making them susceptible to excessive microtrauma and strain, leading to the onset of the condition. The main pathological changes include: in the early stage, degeneration of the cervical intervertebral discs, reduced water content in the nucleus pulposus, and swelling and thickening of the fibers in the annulus fibrosus, followed by hyaline degeneration and even rupture. After degeneration of the cervical intervertebral discs, their compressive and tensile resistance decreases. Under the influence of the skull's gravity and the traction forces of the muscles between the head and thorax, the degenerated discs may bulge locally or extensively, causing narrowing of the intervertebral spaces, overlapping and misalignment of the articular processes, and reduction in the longitudinal diameter of the intervertebral foramina. Due to the weakened tensile resistance of the intervertebral discs, when the cervical spine moves, the stability between adjacent vertebrae decreases, leading to intervertebral instability, increased mobility between vertebral bodies, and grade I spondylolisthesis, followed by osteophyte formation in the posterior facet joints, uncovertebral joints, and laminae, as well as degeneration, chondrification, and ossification of the ligamentum flavum and nuchal ligament.

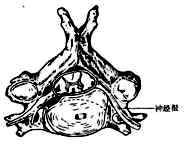

Due to the bulging of the cervical intervertebral discs in all directions, the surrounding tissues (such as the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments) and the vertebral periosteum can be lifted, forming a gap between the vertebral body and the protruding disc as well as the lifted ligament tissue, known as the "ligament-disc gap," which contains tissue fluid abdominal mass. Additionally, bleeding caused by micro-injuries leads to the organization of this bloody fluid, followed by calcification and ossification, resulting in the formation of osteophytes. The loosening of the anterior and posterior ligaments further destabilizes the cervical spine, increasing the likelihood of trauma and causing the osteophytes to gradually enlarge. The osteophytes, together with the bulging annulus fibrosus, posterior longitudinal ligament, and the edema or fibrous scar tissue caused by traumatic reactions, form a mixture protruding into the spinal canal at the level of the intervertebral disc, which may compress the spinal nerves or spinal cord. Osteophytes from the uncovertebral joints can protrude anteriorly or posteriorly into the intervertebral foramen, compressing the nerve roots and vertebral stirred pulse. Osteophytes on the anterior edge of the vertebral body generally do not cause symptoms, but there are reports in the literature of such anterior osteophytes affecting swallowing or causing hoarseness. After compression of the spinal cord and nerve roots, the initial changes are only functional, such as deficient relief under reduced pressure, but irreversible changes may gradually occur. Therefore, if non-surgical treatment is ineffective, surgical intervention should be performed promptly (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Compression of adjacent tissues by degenerative sexually transmitted disease changes in cervical vertebrae and joints

Annulus fibrosus—degeneration and protrusion in the lateral and central regions compressing nerve roots and spinal cord

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms of this disease are highly variable, leading to diagnostic difficulties. The onset typically occurs after the age of 40, with younger individuals being less commonly affected. The disease progresses slowly and initially goes unnoticed, presenting only as neck discomfort. Some patients experience frequent "stiff neck," and over time, radiating pain in the upper limbs gradually develops. Lesions in the upper cervical spine can cause occipital pain, neck stiffness, dizziness, tinnitus, nausea, hearing impairment, visual disturbances, as well as episodes of unconsciousness and sudden falls. Osteophytes in the mid-cervical spine may produce radicular pain in the C3–5 distribution, along with atrophy of the posterior cervical and paravertebral muscles, and may also involve the diaphragm. Lesions in the lower cervical spine can cause pain in the posterior neck, upper back, scapular region, and anterior chest, as well as radicular pain in the C5–T1 distribution. Lesions in the mid-to-lower cervical spine may compress the spinal cord, resulting in paralysis.

Semmes and Murphy observed during surgery that stimulation of the posterior longitudinal ligament or annulus fibrosus could cause pain in the medial scapula, occipital region, and anterior chest. Some surgeons have reported that after blocking the nerve root with procaine and retracting it, compression of the posterior longitudinal ligament over the herniated material also elicited pain along the medial scapular border, shoulder, occiput, neck, and anterior chest wall. If the annulus fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament remain intact, the pain is milder and more diffuse, indicating that these symptoms are unrelated to nerve root involvement.

For convenience, cervical spondylosis can be categorized into radiculopathy, myelopathy, vertebral artery type, and sympathetic type. However, clinically, mixed forms with overlapping symptoms and signs are often observed.(1) Radiculopathy This type results from stimulation or compression of the cervical nerve roots by protrusions in the posterolateral aspect of the cervical spine. It is the most common form, accounting for approximately 60% of cervical spondylosis cases.

Patients experience paroxysmal or persistent dull pain or severe pain in the occipitocervical and cervicoscapular regions. Along the course of the affected cervical nerve root, there may be burning, knife-like, electric shock-like, or needle-prick sensations. Symptoms worsen with neck movement or increased intra-abdominal pressure. Concurrently, the upper limb may feel heavy and weak. The neck exhibits varying degrees of stiffness or painful torticollis deformity, muscle tension, and limited mobility. Tenderness is present at the exit point of the affected cervical nerve root below the corresponding transverse process and beside the spinous process. The brachial plexus traction test is positive, as is the intervertebral foramen compression test (also known as the Spurling test) (Figure 1). Additionally, the affected nerve's dermatome may show sensory disturbances, muscle atrophy, and altered tendon reflexes (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Cervical Spondylosis and Clinical Examination

(1) Brachial plexus traction test; (2) Neck extension compression test; (3) Lateral head compression test

Figure 2: Dermatomal Distribution of Cervical Nerve Segments

Top: Anterior view Bottom: Posterior view

(2) Spinal Cord Type This is caused by compression of the spinal cord by the protruding material. The clinical manifestations involve spinal cord compression, with varying degrees of limb paralysis, accounting for approximately 10–15%. The symptoms of this type are also complex, primarily including limb numbness, soreness, burning sensations, stiffness, weakness, and other symptoms, mostly occurring in the lower limbs before progressing to the upper limbs. However, it may also initially affect one side of the upper or lower limbs. Additionally, symptoms such as headache, dizziness, or abnormalities in urination and defecation may occur. ① Unilateral spinal cord compression: May present with the classic Brown-Séquard Syndrome. ② Bilateral spinal cord compression: Early symptoms may predominantly involve sensory disturbances or motor impairments, with the latter being more common. In the late stage [third stage], it manifests as spastic paralysis of varying degrees due to upper motor neuron or nerve tract damage, such as limb clumsiness, unsteady gait, difficulty walking, or even being bedridden and unable to urinate independently. Physical examination may reveal increased muscle tone in the limbs, weakened muscle strength, hyperactive tendon reflexes, diminished superficial reflexes, and positive pathological reflexes such as Hoffmann and Babinski signs, as well as positive ankle clonus and patellar clonus. The level of sensory impairment often does not correspond to the affected spinal segment and lacks regularity. Additionally, a girdle-like sensation in the chest and waist is a common complaint.

Table 1 Symptoms and signs of cervical nerve root compression

| Nerve Root | Intervertebral Disc | Symptoms | Muscle Strength and Reflex Changes |

| C3 | C2–C3 | Numbness in the skin of the neck and back, pain in the auricle and mastoid process, tenderness along the greater occipital nerve | No clinical findings unless electromyography is performed |

| C4 | C3–C4 | Numbness in the neck and back, pain radiating along the levator scapulae muscle, sometimes extending to the anterior chest | No findings unless electromyography is performed |

| C5 | C4–C5 | Pain radiating along the lateral neck to the shoulder, numbness in the upper part of the deltoid muscle (axillary nerve distribution area), sometimes also in the lateral upper arm and radial forearm, but no effect on the hand | Weakness in upper limb and shoulder extension, especially above 90°, deltoid muscle atrophy, no reflex changes |

| C6 | C5–C6 | Pain radiating to the lateral upper arm and forearm, often to the thumb and index finger. Numbness at the tip of the thumb or the first dorsal interosseous muscle on the back of the hand | Biceps weakness, reduced biceps reflex |

| C7 | C6–C7 | Pain radiating to the mid-forearm and middle finger, but pain is also common in the index and ring fingers. Tenderness along the medial border of the scapula and the pectoralis major muscle | Triceps weakness, reduced triceps reflex, weakened wrist and finger extension |

| C8 | C7–T1 | Pain radiating to the medial forearm, numbness in the ring and little fingers and mid-ring finger, but rarely above the wrist joint | Triceps and small hand muscle weakness, no reflex changes |

(3) Vertebral Artery Type This is caused by compression of the vertebral artery by protrusions, which may result from: ① osteophytes on the lateral side of the intervertebral disc, ② osteophytes anterior to the zygapophyseal joint, ③ posterior joint instability or subluxation. It may also be caused by reflex spasm of the vertebral artery due to stimulation of the cervical sympathetic nerves, accounting for about 10–15% of cervical spondylosis cases. Simple compression may not cause symptoms unless accompanied by vertebral artery atherosclerosis. Symptoms of vertebral artery insufficiency include episodic vertigo, nausea, vomiting, etc. Symptoms often appear when the head is extended or turned to a certain position and disappear when the head is turned away from that position. During head rotation, the patient may suddenly experience limb weakness and fall, usually remaining conscious during the fall. Patients can often identify the triggering posture. Brainstem symptoms include limb numbness, paresthesia, dropping objects, mild contralateral limb weakness, etc. Other symptoms include hoarseness, aphonia, difficulty swallowing, eye muscle paralysis, blurred vision, narrowed visual field, diplopia, and Horner syndrome (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Compression of the vertebral artery due to herniation of the intervertebral disc

(4) Sympathetic Type This type is caused by irritation of the sympathetic nerve fibers on the cervical spinal nerve roots, spinal membrane, and small joint capsules. Symptoms include dizziness, migratory headache, blurred vision, hearing changes, difficulty swallowing, arrhythmia, and sweating disorders. Some also believe it is due to irritation of the nerves on the vertebral artery wall or intermittent blood flow changes in the vertebral artery, which stimulate the surrounding nerves. Diagnosis of this type is difficult and often can only be confirmed after successful treatment trials.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The treatment of cervical spondylosis primarily involves non-surgical therapy. For mild cases, adequate rest and the use of anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications such as indomethacin and piroxicam can alleviate symptoms. Additional therapies like acupuncture and physical therapy can also yield good results. To restrict neck movement, a cervical collar can be worn. Generally, symptoms can be relieved within 2 weeks to 1 month. If symptoms remain significant, traction therapy should be administered. Cervical traction is the main method of non-surgical therapy for cervical spondylosis, aiming to widen the intervertebral spaces and reduce the compressive effect of protruding tissues. However, the primary benefits of traction are actually to allow the neck to rest and relieve muscle spasms.

There are two types of traction: sitting traction and supine traction (Figures 1 and 2). For sitting traction, the patient sits on a stool with a four-point head halter securing the jaw and occiput, pulling vertically upward. The patient's body weight serves as counter-traction, with a weight of 10–20 kg applied for 1–2 hours per session, 1–2 times daily. The duration and weight can be adjusted based on the patient's response, with one course lasting a month. For supine traction, the patient lies on a bed with the head elevated at the foot of the bed. The four-point halter is used at a 30° angle to the body’s longitudinal axis, with a weight of 3 kg applied for 2 hours followed by 1 hour of rest, repeated multiple times a day. One course lasts a month. Most patients with nerve root-type cervical spondylosis can be cured through traction. After completing the traction course, if symptoms are relieved or reduced, a cervical collar should still be used for stabilization.

Figure 1: Cervical traction with a cloth halter

Figure 2: Installation of cervical traction

Cervical spondylosis is not suitable for tuina or manipulative therapy. If tuina is necessary, the techniques should be gentle, avoiding forceful rotational maneuvers. Due to the instability of the patient's cervical spine, forceful manipulation may lead to cervical subluxation or dislocation, or even quadriplegia.

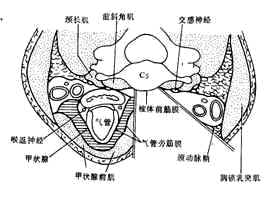

**Surgical Treatment:** If the diagnosis is clear and non-surgical treatments are ineffective, or if there is spinal cord compression, surgery should be performed. In the past, posterior laminectomy decompression was commonly performed, but due to its limited effectiveness, some surgeons began removing protruding tissues by retracting the spinal cord after laminectomy. However, retracting the spinal cord often worsened symptoms and could even cause irreversible paralysis. Since the 1960s, anterior cervical discectomy and interbody fusion have been introduced, yielding excellent results. The anterior approach not only removes protruding tissues but also reduces recurrence by fusing the vertebrae, allowing existing osteophytes to gradually resorb. The surgical procedure involves the patient lying supine with a pillow under the shoulders. A transverse incision is made on the left or right side of the neck, medial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, between the carotid artery and thyroid gland, reaching the vertebral body. A needle is inserted into the targeted intervertebral disc for localization using intraoperative imaging. The disc and adjacent portions of the vertebral body are then removed using an osteotome, drill, or trephine until the posterior longitudinal ligament or dura is exposed. Osteophytes at the posterior edge are further removed with rongeurs or curettes. An iliac bone graft is then placed for interbody fusion. Postoperatively, the neck is immobilized with a cervical collar or plaster cast for 2–3 months. The surgery can be performed under cervical plexus block or acupuncture anesthesia, keeping the patient awake to minimize the risk of nerve root or spinal cord injury (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of the anterior approach incision for cervical spondylosis

bubble_chart Other Related Items