| disease | Tooth Fracture |

Tooth fracture refers to the breakage of a tooth caused by sudden mechanical force. It is most commonly seen in the upper front teeth and is often accompanied by injury to the pulp and periodontal tissues. Severe cases may involve alveolar process fractures. Clinically, it is typically classified based on the location of the fracture into: crown fracture, root fracture, and crown-root fracture.

bubble_chart Etiology

Direct external impact is a common cause of tooth fractures. They can also occur from biting hard objects such as sand, gravel, or bone fragments while chewing.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

According to the anatomical location of the tooth, fractures can be classified into three types: crown fracture, root fracture, and crown-root fracture. In terms of the relationship between the injury and the dental pulp, tooth fractures can also be divided into two categories: exposed pulp and unexposed pulp.

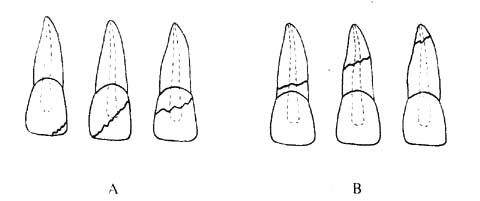

1. Crown Fracture: This can be further divided into horizontal and oblique fractures. For posterior teeth, crown fractures can be classified as oblique or vertical fractures (Figure 3A).

2. Root Fracture: Traumatic root fractures are more common in adult teeth with fully formed roots, as the supporting tissues of young permanent teeth are less stable than those of fully formed roots and are often avulsed or dislocated during trauma, rarely resulting in root fractures. Root fractures are typically caused by direct blows or impacts to the face during falls. Root fractures can be categorized by location into cervical third, middle third, and apical third fractures (Figure 3B). The most common is the apical third fracture. The fracture line is usually perpendicular or at an angle to the long axis of the tooth, while traumatic vertical fractures are rare. X-ray examination is crucial for diagnosing root fractures, but it cannot detect all cases. The fracture line is visible on X-rays only if the central beam aligns with or parallels the fracture line. If the angle between the central beam and the fracture line exceeds ±15°–20°, the fracture line is difficult to observe. Additionally, a radiolucent area can only be detected on X-rays if the mineral content at the corresponding site is reduced by less than 6.6%. X-rays not only aid in diagnosing root fractures but also facilitate follow-up comparisons.

Figure 3 Tooth Fractures

A. Crown Fracture B. Root Fracture

Some affected teeth may show no response to pulp vitality tests during initial examination but may regain responsiveness after 6–8 weeks. It is speculated that the lack of vitality response is due to "shock" caused by vascular and nerve injury to the pulp during trauma, and vitality returns as the "shock" gradually subsides.

The pulp necrosis rate in permanent teeth with root fractures is 20–24%, compared to 38–59% in traumatized permanent teeth without root fractures. This difference may be attributed to the gap at the fracture site, which facilitates drainage of pulp inflammation. Whether pulp necrosis occurs after a root fracture depends mainly on the severity of the trauma, the degree of displacement at the fracture site, and the mobility of the coronal segment, among other factors. Root fractures may present with tooth mobility, percussion pain, and gingival sulcus bleeding if the coronal segment is displaced, as well as tenderness of the periodontal membrane. Some root fractures may show no obvious symptoms initially, with symptoms appearing days or weeks later due to edema and occlusal forces separating the fracture fragments.

3. Crown-Root Fracture: This accounts for a small proportion of dental trauma cases, with oblique crown-root fractures being the most common, often exposing the pulp.

4. Vertical Fracture: This is more common in posterior teeth, with the highest incidence in first molars, followed by second molars, indicating that occlusal forces are the primary causative factor. Additionally, teeth with pulpless or large defects account for over 80% of cases.

Chewing hard objects is a significant direct trigger for vertical fractures.

The most obvious symptom of a vertical tooth fracture is chewing pain, followed by a sensation of elongation. Teeth with vertical root fractures may also exhibit periodontal pockets of varying depths, and X-rays can assist in diagnosis.1. Crown fracture: There is a history of trauma, with enamel and dentin fractures in the crown portion of the tooth. If the pulp is not exposed, only tooth sensitivity symptoms are present. If the pulp is exposed, a pink pulpal exposure point with bleeding can be seen, and probing causes obvious pain.

2. Root fracture: There is a history of trauma, with varying degrees of tooth pain and mobility. The closer to the cervical area, the more pronounced the pain and mobility. Diagnosis can be aided by X-ray imaging.

3. Most cases involve pulp exposure, with obvious occlusal pain. X-ray examination and transillumination can assist in diagnosis respectively.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

1. Crown Fracture For minor crown fractures without dentin exposure, the sharp edges can be polished. If dentin is exposed with grade I sensitivity, desensitization treatment can be performed. For more severe sensitivity, a temporary plastic crown lined with zinc oxide clove oil paste can be cemented. After sufficient reparative dentin formation (6–8 weeks), the crown morphology can be restored with composite resin. At this stage, a calcium hydroxide base should be applied to avoid pulp irritation. For anterior teeth with pulp exposure, pulp extirpation should be performed if root development is complete. For young permanent teeth, pulpotomy should be considered based on the extent of pulp exposure and contamination to facilitate continued root development. Crown defects can be restored with composite resin or artificial crowns.

It should be emphasized that for teeth with vital pulp, follow-up examinations should be conducted at 1, 3, and 6 months post-treatment, and then biannually for several years to assess pulp vitality. Permanent restorations should be performed 6–8 weeks after the injury.2. Root Fracture The primary treatment for root fractures is to promote natural healing. Even if the tooth appears stable, splinting should be applied as early as possible to prevent mobility. Fixation may not be necessary if the tooth is examined weeks after trauma and exhibits minimal mobility.

Generally, the prognosis is better for fractures closer to the root apex. Root fractures confined within the alveolar bone have a favorable prognosis, but fractures involving the gingival sulcus or subgingival fractures often complicate treatment and result in a poorer prognosis.

For fractures in the apical third, splinting alone may suffice in many cases without pulp therapy, allowing repair and maintaining pulp vitality. The notion that root-fractured teeth require prophylactic pulp therapy is incorrect, as immediate root canal treatment may force filling material into the fracture site, hindering repair. However, if pulp necrosis occurs, prompt root canal treatment is necessary.

For fractures in the middle third, splinting is recommended. If the coronal segment is displaced, it should be repositioned before fixation. After fixation, monthly follow-ups are required to check for splint loosening, with replacement if necessary. If pulp necrosis is detected in the coronal segment, pulpectomy should be performed. If the apical segment remains vital, only the coronal segment requires root canal treatment. If the apical segment is necrotic, full root canal treatment is needed. To assess apical segment vitality: after removing the coronal pulp and irrigating, use a smooth broach to check for pain or bleeding, indicating vitality. If the entire pulp is necrotic, complete root canal treatment is required. Instead of gutta-percha, polycarboxylate cement can be used to bond a titanium alloy or cobalt-chromium alloy post into the canal to stabilize the fragments and facilitate cementum deposition. If surgical removal of the apical fragment leaves the coronal segment too short for support, a titanium alloy intraosseous implant post may be inserted to restore tooth length, with coronal splinting. This allows bone growth around the metal "root" to eliminate pathological mobility.

For cervical third fractures communicating with the gingival sulcus, spontaneous repair is unlikely. If the root length permits post-crown restoration, gingivectomy, orthodontic extrusion, or intra-alveolar root repositioning can expose the root for restoration.

Longitudinal root fractures have a poor prognosis, often requiring extraction. In some cases, hemisection or root amputation may be attempted after root canal treatment.

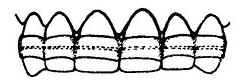

The adhesive splint technique is the simplest method for stabilizing root fractures, with steps as follows:

(1) Reposition the affected tooth, clean the labial surface, wipe with 95% ethanol, dry, and isolate. Repeat for adjacent healthy teeth (at least one tooth on each side).

(2) Take a stainless steel wire with a diameter of 0.4mm, the length of which is equivalent to the width of the affected tooth crown plus the width of at least one normal tooth on each side. Bend it into an arch shape so that it matches the contour of the labial surfaces of these teeth.

(3) Etch the middle 1/3 of the labial surface of the tooth for 1–2 minutes. Rinse with distilled water and dry, then bond the splint to the wire using adhesive and composite resin. Ensure the affected tooth is in its original position (Figure 1). Finally, take an X-ray to check if the alignment of the root fracture segments is satisfactory. For mandibular anterior teeth, the arch splint should be placed on the lingual surface to avoid interfering with occlusion.

Figure 1 Adhesive splinting method

After 3–4 months of fixation, conduct a follow-up clinical examination, X-ray, and vitality test; thereafter, re-examine every 6 months for a total of 2–3 times.

Once the root fracture has healed, remove the composite resin with a diamond bur, loosen the wire, and take it off, then polish the tooth surface.

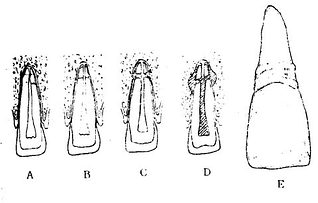

There are four possible outcomes of root fractures:

(1) The two segments unite via calcified tissue, resembling the healing of a bone injury. The hard tissue is formed by cementoblasts differentiated from mesodermal tissue. In teeth with vital pulp, irregular dentin forms on the pulpal side.

(2) The segments are separated by connective tissue, with cementum growth on the fracture surfaces but no union.

(3) The ununited segments are separated by connective tissue and a bony bridge.

(4) The segments are separated by chronic inflammatory tissue, with the apical segment often retaining vital pulp while the coronal segment pulp usually becomes necrotic. This outcome does not represent true repair or healing (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Healing of root fractures

A. Calcific healing B. Connective tissue healing C. Bony and connective tissue union D. Segments separated by chronic inflammatory tissue E. Extracted tooth showing calcific healing of a root fracture (adapted from Fountian)

The first type of healing is primarily observed in teeth without displacement and those fixed early. The second and third types of healing may occur in root-fractured teeth that were not splinted or had no occlusal adjustment. Corresponding to these three histological repair forms, X-rays may also reveal three repair patterns: the fracture line is invisible or nearly invisible; a narrow radiolucent line between segments; rounded edges of the fracture surfaces; or the presence of a bony bridge between segments.

Pulp canal calcification often occurs in root-fractured teeth. Teeth with pulp space reduction due to trauma are characterized by increased collagen components and a decrease in cell numbers.

3. Crown-root fracture For posterior teeth with crown-root fractures that can undergo endodontic treatment, preservation should be attempted whenever possible. After treatment, reinforce with retention pins, then restore with a post-core and full crown; alternatively, an overdenture can be made after root canal therapy. For anterior teeth with crown-root fractures, refer to the treatment principles for cervical root fractures communicating with the oral cavity.