| disease | Congenital Equinovarus |

| alias | Club Foot |

The incidence of congenital talipes equinovarus is 1%, accounting for 85% of foot deformities. The male-to-female ratio is 2:1. Some patients may be accompanied by deformities in other areas, such as congenital hip dislocation or stenosing tenosynovitis. The deformity is easily detectable, ensuring timely treatment. However, it is essential to explain to the family that treatment must be persistent and not abandoned midway. Additionally, long-term follow-up until skeletal maturity (approximately 14 years of age) is necessary; otherwise, partial recurrence may lead to residual deformity.

bubble_chart Etiology

There are many hypotheses about the disease cause of this condition, such as environmental factors, embryonic developmental abnormalities, and genetics, but none can be confirmed with certainty.

Böhm believes that the fetal foot gradually develops from a position of equinus, adduction, and varus to a normal position during embryonic development. During this process, deformities may arise due to certain factors or primary embryonic defects.

Dunn suggests that the deformity is caused by compression of the fetus in the uterus, forcing the forefoot into adduction, supination, and plantarflexion. Stewart observed that Japanese residents in the Hawaiian Islands, who habitually sit in an inverted foot position, have a higher incidence of the condition. This may be due to the sitting posture increasing uterine compression on the fetus, leading to a higher incidence.

Wynne-Davis conducted a family survey of 144 cases from a genetic perspective and concluded that some cases involve hereditary abnormalities, but no clear pattern of dominant or recessive gene inheritance has been identified.

Other theories include Stewart's suggestion that it is related to abnormal muscle insertions. Moore found neural abnormalities, while Sherman attributed it to talar deformities.The current view is that various factors interact in a complex manner, resulting in deformities of varying degrees, and it is by no means attributable to a single cause.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

This disease encompasses four types of deformities: ① forefoot adduction and internal rotation; ② hindfoot varus; ③ ankle joint equinus; ④ tibial internal rotation. Most scholars believe that the primary pathology lies in the tarsal bones, particularly the talus, where the most significant changes occur, leading to the deformities. Over time, soft tissues develop contractures, making the deformities more fixed. During continued development, bones grow more vigorously in areas with less pressure and are hindered in areas with greater pressure, gradually forming bony deformities.

The bone changes occur first: ① In a normal foot, the longitudinal axis of the talar body and its head-neck forms an angle of 150°–155°, whereas in deformity, it becomes 115°–120°, causing the talonavicular joint surface of the talar head to shift from facing forward to facing inward toward the metatarsus. Viewed from the side, the longitudinal axis of the talus shifts from the superolateral to the downward direction, resulting in a similar shift and medial rotation of the calcaneus. The talus assumes a metatarsus flexion position relative to the tibia. ② The shape of the calcaneus remains unchanged, but due to displacement following the talus, it assumes an equinus and internally rotated position, forming a concave arch facing medially. The posterolateral calcaneus contacts the posterior aspect of the lateral malleolus, and the sustentaculum tali contacts the tip of the medial malleolus. ③ The navicular bone is smaller than normal and slightly displaced medially, forming an articular surface on the medial side of the talar head, contributing to the adduction deformity. ④ Other bones, such as the cuneiform and metatarsal bones, show no deformity in the early stages.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

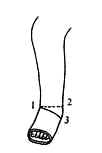

Foot drop, with the heel tilted upward, the lateral edge of the foot touching the ground, and the sole facing backward, resembling a golf club, hence the condition is also called clubfoot. Due to the above phenomena, the heel is inverted, the forefoot is adducted, and the talar head protrudes dorsally and laterally.

The deformity can be divided into two types: ① Slender type (lax type): The foot is small in shape, the deformity is mild, and it is easy to manually position the foot in a neutral position. The calf circumference is similar to that of the healthy side. Non-surgical treatment is effective. ② Short and thick type (rigid type): The foot is thick and short, the heel is small, the deformity is severe, the calf circumference is thinner than that of the healthy side, and the deformity is difficult to correct manually, often requiring surgical treatment.

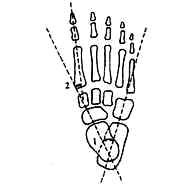

X-ray findings: Anteroposterior X-ray shows the talocalcaneal angle (the angle between the axis of the talus and the axis of the calcaneus) <30°. The angle between the longitudinal axis of the talus and the longitudinal axis of the metatarsus is 0°–20° (Figure 1). The combined measurement results of these two angles are helpful for diagnosis. Lateral X-ray shows the angle between the longitudinal axis of the talus and the tangent of the calcaneal metatarsal surface <30°, otherwise there is foot drop (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Normal X-ray findings (anteroposterior view)

1. The angle between the longitudinal axis of the talus and the longitudinal axis of the calcaneus <30° 2. The angle between the longitudinal axis of the talus and the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal is 0–20°

Figure 2 Normal lateral X-ray of the foot shows the angle between the longitudinal axis of the talus and the calcaneal plantar tangent <30°

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

As early as the time of Hippocrates, there were treatment methods involving manual correction and bandage fixation, followed by subcutaneous Achilles tendonotomy for deformity correction. In the 16th century, violent correction methods emerged, and this one-time mechanical correction approach is still used today. However, this method causes soft tissue injury, leading to local bleeding, fibrosis, and scar contracture, with severe consequences. Therefore, it has been opposed by most scholars in recent years. In 1930, Kite reported the gradual wedge-shaped gypsum excision correction method, which remains one of the best non-surgical treatments to this day. In recent years, surgical treatment has been recommended for cases where non-surgical methods fail, for patients aged over 3-5 years, and for those with short, broad feet.

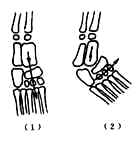

(1) Non-surgical treatment methods Applicable to newborns and young children, these methods include manual correction combined with adhesive tape fixation, gradual gypsum correction, wedge-shaped gypsum excision for gradual correction (Kite method), and the Dennis-Browne splint method. Regardless of the method, the treatment principles are similar: the earlier the treatment begins, the better the outcome, and it should start in the neonatal period. The correction steps should follow the sequence of first correcting adduction, then inversion, and finally equinus deformity. If the adduction deformity is not corrected, the navicular bone remains medial to the talar head; after correction, it moves anterior to the talus, aligning the weight-bearing lines of the forefoot and hindfoot in a straight line, reducing the likelihood of recurrence (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Weight-bearing line before correction of congenital equinovarus adduction deformity

(1) After correction (2) Before correction

If the adduction deformity is not corrected, the weight-bearing line and muscle forces are not in their normal positions. Correcting the inversion deformity first may make it difficult to address both inversion and adduction due to the pull of the tibialis anterior and posterior muscles. Overcorrection of adduction can displace the navicular bone laterally to the talus, leading to flatfoot. If the inversion deformity is not corrected before addressing the equinus deformity, approximately half of the talus remains anterior and superior to the calcaneus (during correction, the talus gradually moves posteriorly while the calcaneus moves anteriorly to its normal position). Meanwhile, the pull of the tibialis posterior and gastrocnemius muscles prevents ankle dorsiflexion, concentrating dorsiflexion stress on the midtarsal joints and resulting in a rocker-bottom foot. This can cause adhesions in the talocalcaneal and tarsal joints, leading to stubborn deformities. Medical staff and family members must persist with treatment and ensure long-term follow-up, avoiding discontinuation midway.

The modified Kite method involves gradual wedge-shaped gypsum excision for correction: First, a gypsum boot is applied to the deformed foot. After drying, a wedge-shaped gypsum excision is performed at the tarsal region (Figure 2). The wedge gap is then closed and reinforced with gypsum, followed by short-leg gypsum fixation in the inverted equinus position. For short, broad feet, long-leg gypsum fixation with knee flexion is used. Weekly wedge-shaped gypsum excisions are performed to gradually correct the deformity. Typically, after 1-2 wedge excisions, the gypsum needs replacement. After 4-6 sessions, the adduction deformity can be corrected.

Figure 2: Wedge-shaped gypsum excision at the tarsal region

1. Navicular bone area 2. Anterior edge of the calcaneus 3. Anterior edge of the metatarsals

After correcting the adduction deformity, the inversion deformity is addressed next.First, make a Gypsum boot. After it dries and hardens, remove part of the Gypsum at the lateral malleolus (to shape it like a shoe). Hold the entire Gypsum boot and gently exert it as much as possible (with moderate force). Fix it in this position using the aforementioned short-leg Gypsum or long-leg Gypsum. Perform a wedge-shaped Gypsum excision at the lateral malleolus once a week (Figure 3). Generally, after 4–6 sessions, the varus deformity can be corrected. After correcting the aforementioned adduction and varus deformities, perform a subcutaneous Achilles tendon tenotomy in the outpatient operating room. Postoperatively, apply a Gypsum boot and excise the Gypsum at the ankle and dorsum of the foot (Figure 4). Then, use a wooden board to dorsiflex and evert the ankle joint (to prevent the development of a cavus foot) and fix it with a short or long-leg Gypsum. After 4 weeks, replace the Gypsum and fix it in a neutral position, concluding the treatment. Regular follow-ups are essential thereafter. If recurrence occurs, correct it with Gypsum, which usually takes about 4 weeks. If follow-up and management are deficient, residual deformity may persist due to recurrence.

Figure 3: Wedge-shaped Gypsum excision for correcting varus deformity

1. Medial malleolus 2. Lateral joint space 3. Midline of the calcaneus

Figure 4: Wedge-shaped excision of the Gypsum boot for correcting equinus deformity

1. Gypsum boot 2. Gypsum excision site

(2) Surgical Therapy Applicable to patients for whom non-surgical treatment has failed or who are older. There are many surgical methods, which can be divided into three categories: soft tissue release, tendon transfer, and bone surgery.

1. Soft Tissue Release Applicable to children aged 3–7 years. During surgery, the deformity must be fully corrected, and residual deformities should not be left to postoperative Gypsum correction. There are numerous surgical techniques, but the following are highlighted.

(1) Correction of Adduction Deformity: Perform a metatarsal-tarsal capsulotomy (Heyman method). Make a transverse curved incision or 2–3 small longitudinal incisions on the dorsum of the foot to expose the 1st–5th metatarsal-tarsal joints. Incise the medial, lateral, and anterior joint capsules to correct the adduction deformity. Fix the forefoot in the corrected position with a short-leg Gypsum for 3 months.

(2) Correction of Varus Deformity: Perform a medial foot release. The Ober method and Brockman method are the most commonly used. This article describes the Ober method. Make a curved incision from the distal tibia to the naviculocuneiform joint at the medial malleolus to expose the distal tibia and medial malleolus. Make an inverted "V" incision in the periosteum above the medial malleolus, reflect the periosteum along with the deltoid ligament downward, and dissect the surrounding soft tissues from the ankle. Continue dissecting along the talus, calcaneus, talocalcaneal joint, and talonavicular joint, and sever the talocalcaneal ligament. During the procedure, the neurovascular bundle and tendons can be retracted. If necessary, perform a "Z" lengthening of the tendons and re-suture them, or sever the talocalcaneal interosseous ligament. After correcting the deformity, fix it with Gypsum for 8 weeks.

(3) Correction of Equinus Deformity: Perform an Achilles tendon lengthening. If there is medial displacement of the Achilles tendon insertion, perform a tendon transfer and suture during the lengthening (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Achilles tendon lengthening and transposition suture

2. Tendon transfer In recurrent cases where the deformity can be manually corrected, if the recurrence is due to muscle imbalance, surgery can be performed according to the treatment principles for sequelae of poliomyelitis.

3. Bone surgery Calcaneal osteotomy is suitable for children aged 3-8 with hindfoot varus deformity. There are two types of osteotomy: opening or closing. The opening type involves making an incision on the medial side of the calcaneus and inserting a wedge-shaped bone graft, while the closing type involves removing a wedge-shaped piece from the lateral side of the calcaneus and closing the osteotomy site.

Arthrodesis is suitable for patients over 12 years old who already have bony deformities. Commonly performed procedures include calcaneocuboid, talocalcaneal, and triple (talonavicular, calcaneocuboid, talocalcaneal) joint fusion.

The various methods described above must be selected based on the patient's age, severity of deformity, as well as the doctor's experience and skill level. Improper treatment can lead to various complications.