| disease | Uterine Fibroids |

| alias | Uterine Leiomyoma, Uterine Myoma, Uterine Leiomyoma |

Uterine myoma is the most common benign tumor in the female reproductive organs and one of the most prevalent tumors in the human body. Uterine myomas primarily arise from the proliferation of uterine smooth muscle cells, with a small amount of connective tissue fibers serving merely as supportive tissue. Therefore, they should not be referred to as fibromyomas, myofibromas, or fibromas based on the amount of connective tissue fibers present. The accurate term for this condition is uterine leiomyoma, commonly known as uterine myoma.

bubble_chart Etiology

To date, the disease cause of uterine fibroids remains unclear. However, extensive clinical observations and experimental results have demonstrated that fibroids are estrogen-dependent tumors. Clinically, they are commonly seen in women of reproductive age, particularly between 30 and 50 years old. Fibroids grow notably in high-estrogen environments, such as during pregnancy or with exogenous high estrogen levels, and tend to shrink after menopause. Patients with fibroids often exhibit ovarian congestion, enlargement, and excessive hyperplasia of the uterine endometrium, suggesting an association with excessive estrogen stimulation.

In fact, the estrogen dependence of fibroids also involves receptors. Recent studies on the relationship between uterine fibroids and endocrinology have experimentally confirmed that fibroid tissues contain estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR), with densities exceeding those of surrounding normal muscle tissue. ER and PR levels fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. Reports indicate that the use of exogenous hormones and clomiphene can lead to the enlargement of uterine fibroids, while suppressing or reducing sex hormone levels can prevent fibroid growth, shrink existing fibroids, and improve clinical symptoms. This further supports the notion that fibroids are sex hormone-dependent tumors. Although hormone-antagonizing drugs can treat fibroids, clinical measurements of sex hormone levels in the peripheral blood of patients with fibroid diseases and women without fibroids show no significant differences. This suggests that the occurrence of fibroids is less related to the systemic hormonal environment of the patient and more to localized endocrine abnormalities within the fibroid itself. For instance, estrogen concentrations within fibroids are higher than in uterine muscle, and the endometrium near fibroids often exhibits higher hyperplasia. Receptor levels follow the same pattern, with higher E2

R (estradiol receptor) and PR content in fibroids compared to uterine muscle.From a histogenetic perspective, it has long been proposed that uterine fibroid cells originate from smooth muscle cells in the uterine muscle and vascular walls, such as immature myoblasts, though the latter remains histologically undefined. Histological studies of small, recently developed uterine fibroids have revealed not only mature smooth muscle cells rich in myofilaments but also immature smooth muscle cells similar to those observed in fetal uteri. This indicates that the development of human uterine fibroids may stem from the differentiation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells into smooth muscle cells. Multiple uterine fibroids may arise from the multifocal潜伏 of progenitor cells within the uterine myometrium. These undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, serving as the原始 cells of fibroids, are胚胎期 cells with multipotent differentiation capabilities. They act as biological mediators, proliferating under estrogen influence and differentiating or hypertrophying under progesterone. After reaching sexual maturity, the residual undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and immature smooth muscle cells in the myometrium undergo a self-perpetuating cycle of proliferation, differentiation, and hypertrophy under the influence of estrogen and progesterone. This process repeats over an extended period until fibroids are formed.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

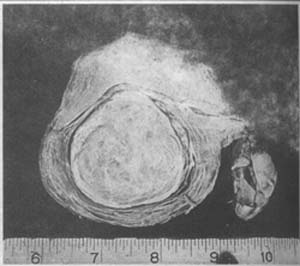

A typical uterine fibroid is a solid, spherical mass with a smooth or uneven surface. The cut surface shows white spiral streaks and slight irregularities. These streaks are formed by the fibrous tissue within the fibroid, and the hardness of the fibroid depends on the amount of fibrous tissue present. The more fibrous tissue there is, the whiter and harder the fibroid becomes. Conversely, if the fibroid contains more smooth muscle cells and less fibrous tissue, the cut surface will resemble the color of the uterine wall and be softer in texture. The fibroid is covered by a thin pseudocapsule, composed of connective tissue bundles and muscle fibers from the surrounding uterine wall. The connection between the pseudocapsule and the fibroid is loose, making it easy to peel the fibroid away from the uterine wall (Photo 2). The pseudocapsule contains radial vascular branches that supply blood and nutrients to the fibroid. The larger the fibroid, the thicker and more numerous these blood vessels become. In the center of the fibroid, vascular branches decrease, and when the fibroid diameter exceeds 4 cm, degeneration is more likely to occur in the central area.

Photo 2: A solitary intramural uterine fibroid with clear boundaries

Uterine fibroids vary greatly in size. Those causing clinical symptoms are typically 8–16 weeks of pregnancy in size. Solitary fibroids generally do not exceed the size of a child's head, while multiple fibroids usually do not exceed the size of a 6-month pregnancy. In rare cases, they can weigh tens of kilograms.

Uterine fibroids can be classified into three types based on their location and relationship to the layers of the uterine wall.

Uterine fibroids initially develop in the myometrium. If they remain within the myometrium, they are called "intramural fibroids" or "interstitial fibroids," which are the most common type (Photo 2). Intramural fibroids are often multiple, with varying numbers, and there may be one or several larger ones. Sometimes, numerous small nodules can be distributed throughout the uterine wall, forming irregular masses and resulting in multiple uterine fibroids (Photo 3). Some may extend to the cervix or even the vaginal fornix during growth, making them easily confused with primary cervical fibroids. Intramural fibroids generally have better blood circulation, so degeneration is less common. However, they can severely distort the uterine body and affect uterine contractions. The increased uterine volume and endometrial surface area often lead to hypermenorrhea, frequent menstruation, and prolonged menstrual periods.

(1) Elder sister, age 38 at surgery

(2) Younger sister, age 37 at surgery

Photo 3: Multiple uterine fibroids (sisters, 4 years apart)

During growth, fibroids tend to expand in the direction of least resistance. When they protrude into the uterine cavity, covered only by a layer of endometrium, they are called "submucous uterine fibroids." Some may even connect to the uterus only by a stalk. Submucous fibroids act as foreign bodies in the uterine cavity, triggering uterine contractions that push them downward, gradually elongating the stalk. When this progresses sufficiently, the fibroid may pass through the cervical canal and prolapse into the vagina or even protrude from the vaginal opening. The uterine wall attached to the stalk is also pulled inward, forming varying degrees of uterine inversion. Due to poor blood supply to the stalk and frequent exposure to the vaginal environment, submucous fibroids are prone to infection, necrosis, and bleeding (Photo 4).

Photo 4: Uterine submucous fibroid showing areas of infection and necrosis in the uterine body and submucous fibroid

If the fibroid protrudes toward the surface of the uterus and is covered by a layer of peritoneum (without a capsule), it is called a "subserosal uterine fibroid" (Photo 5). If it continues to develop toward the abdominal cavity, it may eventually connect to the uterus only by a pedicle, becoming a pedunculated subserosal uterine fibroid. The blood vessels contained in the pedicle are the fibroid's only blood supply. If torsion of the pedicle occurs, the pedicle may become necrotic and detach, causing the fibroid to fall into the abdominal cavity. It may then adhere to adjacent organs or tissues, such as the greater omentum or mesentery, obtaining blood supply and nutrients to become a "parasitic fibroid" or "free fibroid." However, this can lead to partial torsion or obstruction of the greater omentum's blood vessels, resulting in fistula formation, ascites, and other abdominal symptoms.

Photo 5 Subserous fibroid of the uterus

Fibroids that originate from the lateral wall of the uterine body and extend between the two layers of the broad ligament are called "broad ligament fibroids," which belong to the subserous type. However, there is another type of broad ligament fibroid that arises from the smooth muscle fibers near the uterus within the broad ligament and is completely unrelated to the uterine wall. During their growth and development, broad ligament fibroids often cause positional and morphological changes in pelvic organs and blood vessels, particularly displacement of the ureter, making surgical treatment challenging (Photo 6).

Photo 6 Multiple uterine fibroids, with the larger one growing into the broad ligament

Fibroids can also occur in the round ligament and uterosacral ligament of the uterus, but these are relatively rare.

The development of cervical fibroids is similar to that of uterine body fibroids. However, due to their anatomical location, when these fibroids grow to a certain size, they are more likely to cause compression symptoms in adjacent organs, often leading to childbirth obstruction and significantly increasing surgical difficulty (Photo 7).

Photo 7 Cervical fibroid of the uterus

Over 90% of uterine fibroids grow in the uterine body, with only a small minority (4–8%) occurring in the uterine cervix, mostly on the posterior lip. Among those in the uterine body, most are found in the fundus, followed by the posterior wall, while those in the anterior wall are half as common as those in the posterior wall, and fibroids on the sides are the least common. In terms of fibroid types, intramural fibroids are the most prevalent, followed by subserous fibroids, while submucous fibroids are relatively rare.

Microscopic findings: The arrangement of muscle fibers in fibroids resembles that of normal muscle fibers, but the fibers in fibroids are looser and sometimes arranged in an "S" shape or fan-like pattern, forming a distinctive whorled appearance. The muscle fibers are often elongated or thick and short. In long-standing fibroids, the fibers are longer and thicker than normal uterine muscle fibers. Between the muscle fiber bundles, there is a variable amount of connective tissue fibers. Occasionally, fibroids with abundant blood vessels (vascular fibroids) or rich in lymphatic vessels (lymphangiomyomas) may be observed. The nuclei of muscle cells vary in shape, but most are oval or rod-shaped, with deeply stained nuclei. In cross-sections of muscle fibers, the cells appear round or polygonal, with abundant cytoplasm and a central round nucleus; in longitudinal sections, the cells are spindle-shaped with a more distinct elongated nucleus.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of uterine fibroids often vary depending on the location, size, growth rate, presence of secondary changes, and complications of the fibroids. Common clinical symptoms include uterine bleeding, abdominal masses, pain, compression symptoms of adjacent organs, increased leucorrhea, infertility, anemia, and cardiac dysfunction. However, a significant number of patients may also be asymptomatic.

1. **Uterine bleeding** Uterine bleeding is the primary symptom of uterine fibroids, occurring in half or more of the patients. Among these cases, cyclic bleeding (excessive menstruation, prolonged menstruation, or shortened menstrual cycles) accounts for about two-thirds, while non-cyclic (persistent or irregular) bleeding accounts for one-third. Bleeding is mainly caused by intramural fibroids and submucosal fibroids. Cyclic bleeding is more common with intramural fibroids, whereas submucosal fibroids often present as irregular bleeding. Subserosal fibroids rarely cause uterine bleeding. In rare cases, menstrual flow may instead decrease.

The reasons for excessive bleeding caused by fibroids include: ① Fibroid patients often have excessive estrogen levels, leading to concurrent endometrial hyperplasia and polyps, resulting in heavy menstrual flow. ② The enlarged uterine volume due to fibroids increases the endometrial surface area, causing excessive and prolonged bleeding. Particularly with submucosal fibroids, the bleeding area can exceed 225cm² (compared to the normal ~15cm²). 2 ③ Submucosal fibroids often cause ulceration and necrosis of the mucosal surface, leading to chronic endometritis and persistent bleeding. ④ Intramural fibroids impair uterine contraction and vascular clamping, while submucosal fibroids prevent proper contraction due to endometrial shedding, both resulting in heavy and prolonged bleeding. ⑤ Larger fibroids may be associated with pelvic congestion, increasing blood flow volume. ⑥ Menstrual irregularities during perimenopause.

Excessive menstruation or prolonged menstruation may occur alone or in combination. If accompanied by shortened menstrual cycles (frequent menstruation), significant blood loss can lead to severe anemia in a short period. Submucosal fibroids protruding into the vagina may cause non-cyclic bleeding, which can be extremely heavy. Large polypoid fibroids often cause persistent bleeding.

2. **Abdominal masses** Lower abdominal masses are a common complaint among uterine fibroid patients, reported in up to 69.6% of cases. Sometimes, this may be the only symptom. This is particularly true for intramural fibroids that grow outward into the abdominal cavity without affecting the endometrium, especially those located at the uterine fundus or pedunculated subserosal fibroids. Abdominal masses are typically detected after the fibroids extend beyond the pelvic cavity, often becoming noticeable in the morning when the bladder is full. As the uterus and fibroids are pushed upward, patients can easily palpate them. Fibroids larger than a 4–5-month pregnancy uterus can be felt even without a full bladder. Uterine fibroids are generally located in the lower midline of the abdomen, though a few may be off to one side, feeling hard or uneven. Larger fibroids often undergo degeneration, becoming softer and smoother. Most grow slowly. Early post-liberation data reported cases where fibroids grew for up to 22 years before medical consultation, mainly due to the oppression of working women in the old society and lack of access to healthcare. Very rarely, rapid growth or accompanying dull pain may suggest malignant transformation.

3. Pain About 40% of cases present with abdominal pain, 25% with lower back soreness, and 45% with dysmenorrhea. Some may also experience a sensation of lower abdominal heaviness or dull back pain, usually mild in severity. The pain results from the tumor compressing pelvic blood vessels, leading to static blood, or pressing on nerves. Alternatively, pedunculated submucous fibroids may stimulate uterine contractions, causing cervical canal dilation and pain as the fibroid is expelled from the uterine cavity. Pain may also arise from fibroid necrosis, infection-induced pelvic inflammation, adhesions, or traction. In rare cases, red degeneration of uterine fibroids can cause severe abdominal pain accompanied by fever. Acute, intense abdominal pain may also occur due to torsion of a pedunculated subserous fibroid or axial uterine torsion. Large subserous fibroids growing into the broad ligament can compress nerves and blood vessels, causing pain, or obstruct the ureter, leading to hydroureter or hydronephrosis and resulting in lumbago. Severe and progressively worsening dysmenorrhea is often caused by uterine fibroids complicated by adenomyosis or endometriosis.

IV. Compression Symptoms These mostly occur with cervical fibroids or when fibroids in the lower uterine segment enlarge and fill the pelvic cavity, compressing surrounding organs. Compression of the bladder can lead to frequent urination, dysuria, or urinary retention; compression of the ureters may cause hydronephrosis or pyelonephritis. Fibroids on the posterior uterine wall can compress the rectum, leading to constipation or even difficulty in defecation. Compression of pelvic veins may result in lower limb edema. Compression symptoms are more pronounced in the premenstrual period due to congestion and swelling of the fibroids. If subserosal fibroids become incarcerated in the rectouterine pouch, bladder or rectal compression symptoms may also occur.

About 30% of fibroid cases present with compression symptoms, including frequent urination (20%), dysuria (around 10%), anuria (3.3%), urinary retention (5%), painful urination (5%), constipation (20%), and lower limb edema (6%).

V. Leucorrhea Increased leucorrhea occurs in 41.9% of cases. Enlargement of the uterine cavity, increased endometrial glandular tissue, pelvic congestion, or inflammation can all contribute to increased leucorrhea. When submucosal fibroids ulcerate, become infected, bleed, or necrotize, bloody or foul-smelling purulent leucorrhea may be produced, sometimes in large quantities.

VI. Infertility and Late Miscarriage 30% of uterine fibroid patients experience infertility. Infertility may be the reason for seeking medical attention, leading to the discovery of fibroids during examination. The causes of infertility due to uterine fibroids are multifaceted (see the section on uterine fibroids combined with pregnancy).

The rate of spontaneous late miscarriage is higher than in the general population, with a ratio of 4:1.

VII. Anemia Prolonged bleeding without timely treatment can lead to anemia. Before liberation, many working women, due to harsh living conditions, suffered persistent uterine bleeding without access to treatment, resulting in anemia. In the early post-liberation period, data on uterine fibroid patients showed that 45.25% had hemoglobin levels between 5–10 g, while 12.4% had levels below 5 g, mostly submucosal fibroids. Severe anemia (below 5 g) can lead to anemic heart disease or myocardial degeneration.

VIII. Hypertension Some uterine fibroid patients also have hypertension. Statistics show that in cases where fibroids are associated with hypertension (excluding those with a history of hypertension), blood pressure often normalizes after fibroid removal, possibly due to relief of ureteral compression.

IX. Signs Fibroids smaller than a 3-month pregnancy uterus are usually not palpable abdominally. Palpable fibroids are typically located in the lower mid-abdomen, firm, and often irregular. In thin patients, the tumor's outline may be clearly felt or even visible. Bimanual pelvic examination can usually delineate the fibroid's outline clearly. Fibroids on the anterior or posterior uterine wall cause localized bulging; multiple fibroids present as several smooth, hard, spherical masses on the uterus. A hard mass protruding laterally may indicate a broad ligament fibroid. A markedly enlarged cervix with a palpable normal uterus above suggests a cervical fibroid. Uniform uterine enlargement and firmness may indicate a submucosal fibroid within the uterine cavity or cervical canal. If the cervical os is relaxed, a smooth, spherical tumor may be felt digitally; some may protrude through the cervical os or even into the vagina, making diagnosis straightforward. However, secondary infection, necrosis, or large size may obscure the cervix, leading to confusion with cervical malignancy or uterine inversion.

The fibroid's location can also affect the position of the uterine body and cervix. For example, posterior wall fibroids may push the uterine body and cervix forward. If posterior wall fibroids extend into the rectouterine pouch, the uterus may be displaced upward behind the pubic symphysis, making the uterine outline palpable in the lower abdomen while the cervix moves upward, causing the vaginal posterior wall to bulge forward and making the cervix unreachable on digital exam. Broad ligament fibroids often push the uterine body to the opposite side.

In cases of fibroid degeneration, aside from changes in the mass's texture and size on palpation, its relationship to the uterine body and cervix remains as described above.

10. Changes in the patient's general condition, such as nutrition, anemia, cardiac function, and urinary system status, are related to the duration of the disease, the amount of bleeding, or other complications.

If there is a typical history and signs of uterine fibroids, and after bimanual examination, comparing with the above characteristics, the diagnosis is usually not difficult. However, this is not always the case, especially for very small asymptomatic fibroids, or fibroids combined with pregnancy, uterine adenomyosis, or fibroids with cystic degeneration and adnexal inflammatory masses, etc., misdiagnosis can sometimes occur, with a general misdiagnosis rate of about 6%. Additionally, uterine bleeding, pain, and pressure symptoms are not unique to uterine fibroids. Therefore, bimanual examination is an important method for diagnosing fibroids. For cases where bimanual examination cannot provide a clear diagnosis or when submucosal fibroids in the uterine cavity are suspected, the following auxiliary examination methods should be adopted.

Cervical fibroids or broad ligament fibroids, especially when they grow larger, often affect the correct diagnosis due to positional changes. For example, when a posterior cervical fibroid grows large, it may become incarcerated in the pelvis and protrude into the vagina, causing the posterior fornix to disappear; or an upper cervical fibroid may grow into the abdominal cavity, with the normal uterine body sitting on top of the cervical fibroid, leading to the uterine body being mistaken for a tumor. Moreover, the cervix may be displaced behind the pubic arch, making it difficult to clearly expose, especially when a broad ligament fibroid grows to a certain size and becomes incarcerated in the pelvis or rises into the abdominal cavity, the cervix may shift upward and become difficult to expose clearly. Therefore, any pelvic mass with a difficult-to-expose cervix can help in diagnosing fibroids in these two special locations.

1. **Ultrasonography** Currently, B-ultrasound examination is quite common in China. For differentiating fibroids, the accuracy rate can reach 93.1%. It can show uterine enlargement and irregular shape; the number, location, size of fibroids, and whether the fibroids are homogeneous or have liquefied cystic changes; as well as whether surrounding organs are being compressed. Due to the dense tumor cells per unit volume in fibroid nodules, the content of connective tissue framework, and the arrangement of tumor cells, fibroid nodules may appear as hypoechoic, isoechoic, or hyperechoic during scanning. The hypoechoic type has high cell density, abundant elastic fibers, and mainly nested cell arrangement with relatively rich blood vessels. The hyperechoic type has more collagen fibers, with tumor cells mainly arranged in bundles. The isoechoic type is intermediate between the two. Posterior wall fibroids are sometimes not clearly visible. The harder the fibroid, the more pronounced the attenuation, with benign attenuation being more obvious than malignant. When fibroids undergo degeneration, acoustic penetration increases. In cases of malignant transformation, the necrotic area enlarges, and the internal echoes become disordered. Therefore, B-ultrasound not only aids in diagnosing fibroids and distinguishing whether they have degenerated or become malignant but also helps differentiate ovarian tumors or other pelvic masses.

2. **Uterine Cavity Probing** Using a probe to measure the uterine cavity, intramural or submucosal fibroids often cause the uterine cavity to enlarge and deform. Thus, a uterine probe can be used to measure the size and direction of the uterine cavity, which, when compared with bimanual findings, helps determine the nature of the mass and identify any intra-cavity masses and their locations. However, it must be noted that the uterine cavity is often tortuous or blocked by submucosal fibroids, preventing the probe from fully entering, or in the case of subserosal fibroids, the uterine cavity may not enlarge, leading to misdiagnosis.

3. **X-ray Plain Film** When fibroids calcify, they appear as scattered uniform spots, shell-like calcified membranes, or rough-edged and wavy honeycomb patterns.

4. **Diagnostic Curettage** Small submucosal fibroids or dysfunctional uterine bleeding and endometrial polyps, which are difficult to detect with bimanual examination, can be diagnosed with curettage. For submucosal fibroids, the curette may feel a raised surface in the uterine cavity, initially high and then sliding lower, or sense something sliding inside the cavity. However, curettage can scrape the tumor surface, causing bleeding, infection, necrosis, or even sepsis. Strict aseptic techniques and gentle handling are required, and the scraped material should be sent for pathological examination. If submucosal fibroids are suspected but diagnostic curettage is inconclusive, hysterography can be performed.

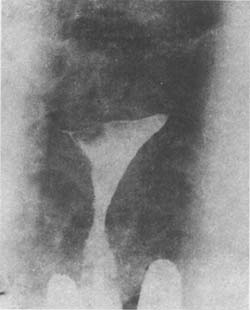

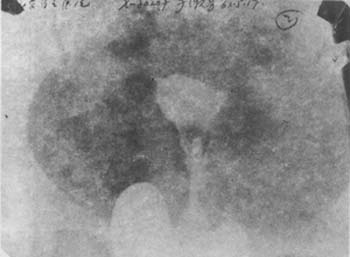

5. **Hysterosalpingography** Ideal hysterography can not only show the number and size of submucosal fibroids but also locate them. Therefore, it is very helpful for the early diagnosis of submucosal fibroids and is a simple method. The radiograph of the fibroid area shows filling defects in the uterine cavity (Photo 1).

(1) Hysterosalpingogram showing a filling defect in the right cornu of the uterus due to a submucous myoma.

(2) Hysterosalpingogram of a uterus with a submucous myoma prolapsed into the cervical canal, demonstrating filling defects in the lower uterine cavity and cervix.

Image 1: Hysterosalpingogram of uterine myoma.

6. CT and MRI Generally, these two examinations are not necessary. CT diagnosis of myomas only displays detailed content within specific cross-sectional layers without overlapping image structures. The CT image of a benign uterine tumor shows volume enlargement, uniform structure, and density of +40 to +60H (normal uterus is +40 to +50H).

In MRI diagnosis of myomas, different signals are produced depending on the presence, type, and degree of degeneration within the myoma. Myomas without degeneration or with grade I degeneration typically exhibit uniform internal signals. Conversely, those with significant degeneration show varying signals.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

The treatment of uterine fibroids depends on factors such as the patient's age, presence of symptoms, location of the fibroids, size, growth rate, number, degree of uterine deformation, whether fertility preservation is desired, and the patient's preferences. The management approaches include the following:

**1. Expectant Management** For small fibroids with no symptoms, complications, or degeneration, and no impact on health, expectant management may be adopted. Perimenopausal patients with no clinical symptoms may also consider this approach, as ovarian function decline could lead to fibroid regression or shrinkage. In such cases, regular clinical and imaging follow-ups (every 3–6 months) are recommended, with further management decisions based on re-evaluation.

Typically, fibroids naturally regress after menopause, making surgical intervention unnecessary. However, for patients in their 40s who are still years away from menopause, surgery may be considered. Conservative drug therapy can be attempted first; if effective, surgery may be postponed. It is important to note that, in rare cases, fibroids in postmenopausal women may enlarge rather than shrink, necessitating closer follow-up.

**2. Drug Therapy** Significant advancements have been made in drug treatments for fibroids.

**(1) Indications for Drug Therapy**

1. Young patients who wish to preserve fertility. For women of reproductive age experiencing infertility or late abortion due to fibroids, drug therapy may shrink the fibroids, promoting conception and fetal survival.

2. Premenopausal women with relatively small fibroids and mild symptoms may use medication to induce uterine atrophy and menopause, allowing fibroids to regress and avoiding surgery.

3. Patients with surgical indications but contraindications requiring prior treatment before surgery.

4. Patients with comorbid medical or surgical conditions who are unfit for or unwilling to undergo surgery.

5. Before initiating drug therapy, a diagnostic curettage with endometrial biopsy should be performed to exclude malignancy, especially in cases of menstrual irregularities or heavy bleeding. Curettage also serves diagnostic and hemostatic purposes.

The rationale for drug therapy lies in the fact that uterine fibroids are hormone-dependent tumors. Thus, drugs that antagonize sex hormones are used. Recent approaches involve temporary ovarian suppression. Danazol and gossypol are commonly used in China, along with androgens, progestins, and vitamins. Since 1983, studies have reported the successful use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa) to shrink uterine fibroids. Research shows that GnRHa indirectly reduces pituitary gonadotropin secretion, effectively suppressing ovarian function—a phenomenon known as "downregulation."

**(2) Types and Administration of Drugs**

1. **LHRH Agonists (LHRH-A):** Also known as GnRHa, these are a newer class of drugs for gynecological conditions. Prolonged high-dose LHRH saturates pituitary receptors, inhibiting FSH and LH synthesis and release. Additionally, LHRH has extra-pituitary effects, increasing ovarian LHRH receptors and reducing estrogen and progesterone production. By significantly suppressing FSH and ovarian hormone secretion, LHRH-A mimics a "medical oophorectomy," leading to fibroid shrinkage. LHRH and LHRH-A are functionally similar but the latter is dozens of times more potent.

Usage: LHRH-A is mostly administered via intramuscular injection, but can also be used for subcutaneous implantation or nasal spray. Starting from the first day of menstruation, inject 100–200μg intramuscularly for 3–4 consecutive months. Its effect depends on the applied dose, route of administration, and timing in the menstruation cycle. After treatment, fibroids shrink by an average of 40–80%, with symptom relief and anemia correction. Serum E2 levels decrease in line with fibroid shrinkage. FSH and LH show no significant changes. Shortly after discontinuation, fibroids regrow, indicating that the effect of LHRH-A is temporary and reversible. If used during perimenopause, it can induce natural menopause within a limited timeframe. For fertility preservation, when fibroids shrink and local blood flow decreases, it reduces surgical bleeding and minimizes the surgical scope. Alternatively, for fibroids obstructing the fallopian tube ostium, treatment-induced shrinkage can restore tubal patency and improve pregnancy rates. To mitigate post-treatment fibroid regrowth, sequential administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate 200–500mg during LHRH-A therapy can sustain its efficacy.

Side effects include tidal fever, sweating, vaginal dryness, or bleeding disorders. Due to low estrogen effects, osteoporosis may occur.

2. Danazol: Has weak androgenic effects. Danazol inhibits hypothalamic and pituitary function, reducing FSH and LH levels, thereby suppressing ovarian steroid production. It can also directly inhibit enzymes involved in ovarian steroid synthesis, leading to decreased estrogen levels, which suppresses uterine growth and causes endometrial atrophy and amenorrhea. At the same time, fibroids shrink. However, in younger patients, menstruation may resume 6 weeks after discontinuation, requiring repeated use.

Dosage: 200mg, taken orally 3 times daily, starting from the second day of menstruation for 6 consecutive months.

Adverse reactions include tidal fever, sweating, weight gain, acne, and elevated liver enzymes (SGPT; liver function should be checked before and after use). These effects resolve 2–6 weeks after discontinuation.

3. Gossypol: A dialdehyde naphthalene compound extracted from cottonseed. It acts on the ovaries without suppressing the pituitary gland. It specifically atrophies the uterine endometrium and inhibits endometrial receptors, causing degeneration of uterine muscle cells, resulting in pseudomenopause and uterine atrophy. Known as "Chinese Danazol," it improves symptoms of uterine fibroids in 93.7% of cases and shrinks fibroids in 62.5%.

Dosage: 20mg, taken orally once daily for 2 months, followed by 20mg twice weekly for 1 month, then once weekly for another month (total 4 months). Due to its side effect of renal potassium loss, liver and kidney function and potassium levels should be monitored. Potassium citrate (10%) is often co-administered. Ovarian function recovers after discontinuation.

4. Vitamins: Vitamin therapy for uterine fibroids works by reducing uterine muscle sensitivity to estrogen and regulating the neuroendocrine system, normalizing steroid hormone metabolism and promoting fibroid shrinkage. In 1980, Soviet researcher Palladii reported over 80% efficacy using vitamin A combined with vitamins B, C, and E for small fibroids, with no side effects. In China, Bao Yan achieved a 71.6% cure rate. This method is suitable for small fibroids.

Dosage: Vitamin A 150,000 IU daily from the 15th to 26th day of menstruation. Vitamin B complex, 1 tablet 3 times daily from the 5th to 14th day. Vitamin C, 0.5g twice daily from the 12th to 26th day. Vitamin E, 100mg once daily from the 14th to 26th day. Continue for 6 months.

5. Androgens: Counteract estrogen, control uterine bleeding (hypermenorrhea), and prolong the menstrual cycle.

Dosage: Methyltestosterone 10mg sublingually once daily for 3 months. Alternatively, testosterone propionate 25mg intramuscularly once daily for 8–10 days starting 4–7 days after menstruation stops can achieve hemostasis. Long-acting testosterone phenylacetate is 3 times more potent than testosterone propionate; 150mg is injected 1–2 times monthly. Masculinization is rare and reversible upon discontinuation. Androgen use should not exceed 6 months; if reuse is needed, pause for 1–2 months.

At the above doses, long-term use is generally safe. It can induce menopause in perimenopausal women, stopping bleeding. Androgens not only halt fibroid growth but also shrink fibroids in 1/3 to 1/2 of patients. Due to water and salt retention, caution is needed in patients with heart failure, cirrhosis, chronic nephritis, or edema. Some scholars avoid androgens, as fibroid development may also be androgen-related.

6. Progesterone: Progesterone acts as an antagonist to estrogen to some extent and can inhibit its effects. Therefore, some scholars use progesterone to treat uterine fibroids accompanied by persistent follicles. Commonly used progestins include medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera), megestrol (Megace), and norethisterone (Norlutin). Depending on the patient's specific condition, cyclic or continuous pseudocyesis therapy may be employed to induce degeneration and softening of the fibroids. However, because it may cause tumor enlargement and irregular uterine bleeding, long-term use is not recommended.

Medroxyprogesterone: For cyclic therapy, take 4mg orally daily from the 6th to the 25th day of menstruation. For continuous therapy: 4mg three times daily in the first week, 8mg twice daily in the second week, followed by 10mg twice daily. Continue for 3–6 months. Alternatively, 10mg three times daily for 3 months.

Norethisterone: For cyclic therapy, take 5–10mg orally daily from the 6th to the 25th day or the 16th to the 25th day of menstruation. For continuous therapy: 5mg once daily in the first week, 10mg once daily in the second week, followed by 10mg twice daily. Continue for 3–6 months.

7. Tamoxifen (TMX): TMX is a nonsteroidal antiestrogen derived from stilbene. It competitively binds to cytoplasmic estrogen receptors (ER), forming TMX-ER complexes that translocate to the nucleus and persist long-term. TMX acts first on the pituitary, then the ovaries, while also exerting direct effects on the ovaries. TMX is more effective in ER-positive cases.

Dosage: 10mg three times daily orally for 3 months per course. Side effects include grade I tidal fever, nausea, sweating, and delayed menstruation.

8. Gestrinone (R2323): Also known as Nemestran, it is a 19-nortestosterone derivative with strong antiestrogenic effects. It suppresses pituitary FSH and LH secretion, lowering estrogen levels and shrinking the uterus, primarily used for treating uterine fibroids.

Dosage: 5mg vaginally three times weekly, preferably for long-term use to prevent rebound uterine enlargement. Significant uterine shrinkage is observed in the first 6 months. Side effects include acne, tidal fever, and weight gain.

For fibroid patients with heavy bleeding during menstruation, uterine contractions or oral/intramuscular hemostatics may be used, such as motherwort herb liquid extract, motherwort herb paste, oxytocin, or ergot alkaloids. Hemostatics include Funing, Sanqi tablets, etamsylate, aminomethylbenzoic acid, tranexamic acid, and 6-aminocaproic acid. Calcium can enhance uterine tone and blood coagulation and may be tried, e.g., 10% calcium gluconate (5–10ml IV) or 5% calcium chloride (30–35ml as a warm enema).

If vaginal bleeding persists despite hemostatics, diagnostic curettage can aid diagnosis and stop bleeding.

Correct anemia with vitamins, iron supplements, or blood transfusion.

Traditional Chinese medicine can reduce menstrual flow (see menstrual disease chapter).

If drug therapy fails to alleviate symptoms or malignancy is suspected, surgical intervention is warranted.

III. Surgical Treatment The age for hysterectomy with adnexal removal in fibroid patients was traditionally set at ≥45 years. Current practice prioritizes individualized decisions, especially considering advances in gynecological endocrinology. Ovarian preservation is generally recommended for those ≤50 years (average menopause age: 49.5). Even postmenopausal ovaries with normal function should be retained, regardless of age, as they maintain endocrine activity for 5–10 years postmenopause, stabilizing autonomic nerves and aiding metabolic transition to old age. The uterus, as an ovarian target organ, also has endocrine roles and should not be removed unnecessarily. Hysterectomy is typically advised for ≥45 years, while myomectomy is preferred for younger patients, especially those <40. If adnexal preservation is feasible, bilateral retention is superior to unilateral. The ovarian cancer rate after ovarian preservation is 0.15%, no higher than in non-hysterectomized women.

(1) Myomectomy: This is a procedure to remove fibroids from the uterus while preserving the uterus itself. It is primarily indicated for women under 45 years of age, especially those under 40. This surgery is not only performed for women with infertility due to childlessness but also for those who already have children if the fibroids are large (diameter greater than 6 cm), if hypermenorrhea persists despite conservative drug treatment, if there are compression symptoms, if the fibroids are submucosal, or if the fibroids are growing rapidly. For the sake of physical and mental health, myomectomy should also be considered. As for the number of fibroids, the procedure is generally limited to cases with fewer than 15 fibroids. However, there have been instances where women urgently desiring children underwent the removal of even more fibroids—sometimes over 100—and subsequently conceived. The highest number of fibroids removed at Shandong Provincial Hospital was 116.

If the fibroid shows malignant transformation accompanied by severe pelvic adhesions, such as subcutaneous nodules or endometriosis, or if cervical cytology is highly suspicious for malignancy, these are contraindications for myomectomy.

For patients undergoing myomectomy, it is preferable to perform a preoperative pathological examination of the endometrium to exclude precancerous or cancerous lesions of the endometrium. During surgery, attention should be paid to whether the fibroid shows malignant changes, and if suspicious, a rapid frozen section should be performed.

For transabdominal myomectomy, to prevent postoperative intra-abdominal adhesions, the uterine incision should preferably be made on the anterior wall, with as few incisions as possible. Multiple fibroids should be removed through a single incision whenever feasible. Additionally, penetration of the endometrium should be avoided as much as possible. Hemostasis of the incision must be thorough, and suturing should leave no dead space. After the procedure, the uterine incision should ideally be peritonealized. For submucosal fibroids that have prolapsed into the cervix, the fibroid can be removed vaginally. During removal, excessive traction should be avoided to prevent injury to the uterine wall. For those that have not prolapsed, transabdominal uterine incision may be performed for removal. Postoperative management should include hemostatic medications and antibiotics. For patients who have not been pregnant, contraception for 1–2 years is recommended. In future pregnancies, vigilance for uterine rupture and placenta accreta is necessary, and elective cesarean section at term is advisable. There is also a possibility of fibroid recurrence after myomectomy, so regular follow-up examinations are recommended.

(2) Hysterectomy: If expectant or medical therapy fails to improve symptoms and the patient is not a candidate for myomectomy, hysterectomy should be considered. Hysterectomy options include total hysterectomy or supracervical hysterectomy. Hysterectomy is primarily performed transabdominally, but in cases of small tumors, absence of adnexal inflammatory adhesions, severe obesity, or abdominal wall eczema, a vaginal approach may be considered.

The advantages of the transabdominal approach include simpler technical execution and less bleeding. Large fibroids or adnexal adhesions can also be managed more easily. A limitation is that if rectocele, cystocele, or vaginal wall laxity is present, additional vaginal surgery may be required.

Cervical or broad ligament fibroids, as well as cases involving severe pelvic organ (ureter, bladder, rectum, major blood vessels, etc.) anatomical variations and adhesions due to zabing, can pose significant surgical challenges. These issues are discussed in detail in gynecological surgical texts.

Large submucosal fibroids causing hemorrhage and secondary severe anemia generally require surgery (either simple myomectomy or hysterectomy) after blood transfusion to improve the patient’s condition. However, in remote rural areas where blood supply is limited, if bleeding persists and the patient cannot be moved, and if the cervical os is dilated with the fibroid protruding through the cervix or near the vaginal opening, vaginal removal of the fibroid may be more effective in achieving hemostasis and stabilizing the patient.

Total hysterectomy is generally recommended, especially in cases of significant cervical hypertrophy, laceration, or severe erosion. However, if the patient’s condition is poor or technical limitations exist, supracervical hysterectomy may be performed, with a residual cervical stump cancer incidence of only 1–4%. Regular postoperative follow-up is still advised.

IV. Radiation Therapy Radiation therapy is used for patients who do not respond to medical therapy and have contraindications to or refuse surgery. However, there are certain contraindications:

(1) Patients under 40 years of age should generally avoid radiation therapy to prevent premature menopause symptoms.

(2) Submucosal fibroids (broad-based submucosal fibroids may be treated with X-ray therapy). Radium therapy can lead to necrosis and severe intrauterine or pelvic infections.

(3) Pelvic inflammatory disease: Acute or chronic pelvic inflammation, especially if adnexal abscess is suspected, is a contraindication, as radiation may exacerbate inflammation.

(4) Fibroids larger than a 5-month gestational uterus or cervical fibroids often do not respond well to intracavitary radium therapy.

(5) Fibroids with malignant or suspicious malignant transformation.

(6) Concurrent presence of uterine fibroids and ovarian tumors.

(1) Infection and Suppuration: Fibroid infection is mostly a result of pedicle torsion or Garden Balsam Seed intrauterine membrane inflammation, with hematogenous infection being extremely rare. Infection can sometimes become suppurative, and in a few cases, abscesses form within the tumor tissue.

Subserosal fibroids with pedicle torsion may develop intestinal adhesions and become infected by intestinal bacteria. Inflamed fibroids adhering to uterine appendages can lead to suppurative inflammation.

Submucosal fibroids are most prone to infection, often coexisting with Garden Balsam Seed intrauterine membrane inflammation after late abortion or during the puerperium. Some cases are caused by injuries from curettage or obstetric procedures. Due to tumor protrusion or surgical trauma, the tumor capsule may rupture, making it susceptible to infection and subsequent necrotic collapse. Necrotic collapse often causes severe irregular bleeding and fever. The expelled necrotic debris, due to the loss of staining reaction in necrotic tissue, often yields no results under microscopic examination.

(2) Torsion: Subserosal fibroids may undergo torsion at the pedicle, causing acute abdominal pain. Severe pedicle torsion, if not surgically addressed or spontaneously resolved, may lead to detachment of the fibroid, forming a free fibroid, as mentioned earlier. Torsion of the fibroid may also drag the entire uterus, causing axial torsion of the uterus. Uterine torsion usually occurs near the internal os of the cervical canal, though this is rare and mostly results from larger subserosal fibroids attached to the uterine fundus combined with an elongated cervical canal. The symptoms and signs resemble those of ovarian cyst torsion, except that the mass is harder.

(3) Uterine Fibroids Combined with Uterine Body Cancer: Uterine fibroids coexisting with uterine body cancer account for 2%, significantly higher than those combined with cervical cancer. Therefore, perimenopausal patients with persistent uterine bleeding should be alert to the possibility of coexisting endometrial carcinoma. Diagnostic curettage should be performed before treatment is determined.

(4) Uterine Fibroids Combined with Pregnancy.

Uterine fibroids are often easily confused with the following diseases and should be differentiated.

1. Ovarian tumors: Subserosal uterine fibroids and solid ovarian tumors, fibroids with cystic degeneration and highly tense cystic ovarian tumors, or ovarian tumors adherent to the uterus pose certain difficulties in differentiation. A detailed menstrual history and the growth rate of the abdominal mass (malignant ovarian tumors grow faster) should be obtained. A thorough gynecological examination should be performed. If the abdominal wall is tense and the gynecological examination is unsatisfactory, examination under anesthesia or analgesics may be necessary. The examination includes a rectal exam to determine if the uterine body can be separated from the mass, and a uterine sound can be used to measure the length and direction of the uterine cavity. A comprehensive analysis should be made based on the disease history and examination. When differentiation is difficult, an intramuscular injection of 10 units of oxytocin can be administered. If the mass contracts after injection, it is a uterine fibroid; otherwise, it is an ovarian tumor. In most cases, B-ultrasound imaging can distinguish between them. However, some cases can only be confirmed during surgery.

2. Intrauterine pregnancy: In the first three months of pregnancy, some pregnant women may still experience slight monthly bleeding. If this is mistaken for normal menstruation and the uterus is enlarged, it is often misdiagnosed as a fibroid. A detailed menstrual history (including the amount of flow), any history of childbirth, and age (younger women are less likely to have fibroids) should be obtained. Pregnancy reactions should also be noted. In pregnancy, the uterine enlargement corresponds to the months of reduced menstruation; fibroids make the uterus harder. Additionally, in pregnancy, the vulva and vagina appear bluish-purple, the cervix is soft, the breasts feel full, and secondary areolas may appear around the nipples. After four months of pregnancy, fetal movement can be felt or fetal heart sounds heard, and uterine contractions can be detected by manual palpation. Besides history and signs, pregnancy tests or B-ultrasound imaging can be used for differentiation.

Missed abortion with irregular vaginal bleeding and a negative urine pregnancy test can be easily misdiagnosed as a uterine fibroid. However, missed abortion involves a history of missed periods and previous pregnancy reactions, and the uterine shape is normal. B-ultrasound can usually confirm the diagnosis. If necessary, diagnostic curettage can be performed for differentiation.

Uterine fibroids can coexist with pregnancy, which must be considered; otherwise, pregnancy may be misdiagnosed as a fistula disease or mistaken for a hydatidiform mole. If fibroids were previously detected and there is a history and signs of early pregnancy, with the uterus larger than the expected gestational age, no vaginal bleeding, and a positive pregnancy test, the diagnosis should be straightforward. However, if there was no previous diagnosis, detailed inquiries about excessive menstruation and infertility history should be made. During examination, note if the uterus has protruding fibroids, and close observation may be necessary if required. In the case of a hydatidiform mole, slight vaginal bleeding often occurs after a missed period, and the abdominal mass grows rapidly in a short time, with a positive pregnancy test and high titers; B-ultrasound shows the characteristic snowflake-like pattern of a hydatidiform mole.

3. Uterine adenomyosis: More than half of women with uterine adenomyosis experience secondary, severe, and progressive dysmenorrhea, often with primary or secondary infertility. However, the uterus rarely exceeds the size of a 2–3-month pregnancy. If accompanied by extrauterine endometriosis, painful small nodules may sometimes be palpated in the posterior fornix. Progesterone therapy can also be tried to observe its effects for differentiation (refer to the chapter on endometriosis). However, uterine fibroids coexisting with adenomyosis are not uncommon, accounting for about 10% of fibroid cases. C-ultrasound is more helpful for differentiation. For other asymptomatic cases or those undetected by B-ultrasound, the diagnosis is often only confirmed by pathological examination of surgically removed specimens.

4. Uterine hypertrophy: This condition also causes hypermenorrhea and uterine enlargement, which can be confused with small intramural fibroids or submucosal fibroids in the uterine cavity. However, uterine hypertrophy often involves a history of multiple births, with uniform uterine enlargement and no irregular nodules. The uterine enlargement is typically around two months' pregnancy size, the uterine cavity shows no deformation upon probing, and no masses are felt. B-ultrasound does not reveal fibroid nodules.

5. Pelvic inflammatory mass The inflammatory mass in the adnexa often adheres tightly to the uterus and is frequently misdiagnosed as a myoma. However, pelvic inflammatory masses usually have a history of large size, acute or subacute infection following late abortion, followed by lower abdominal pain and lumbago. Gynecological examination often reveals that the mass is bilateral, relatively fixed, and markedly tender, whereas myomas are usually non-tender. Although the mass is closely related to the uterus, careful examination can often identify the normal uterine contour. If the examination is unclear, the uterine cavity can be probed or a B-ultrasound examination can be performed to assist in differentiation.

VI. Cervical cancer or carcinoma of endometrium. Larger pedunculated submucous fibroids protruding into the vagina with infection and ulceration can cause irregular vaginal bleeding, heavy bleeding, and foul-smelling discharge, which may be confused with exophytic cervical cancer, especially in rural areas. During examination, fingers should gently bypass the mass to palpate the dilated cervical os and the pedicle of the tumor, whereas cervical carcinoma does not have a pedicle. Pathological examination may be performed if necessary for differentiation.

Submucous fibroids in the uterine cavity with secondary infection, bleeding, and increased leucorrhea can be easily confused with carcinoma of endometrium. Diagnosis may begin with B-ultrasound and uterine cavity cytology, followed by diagnostic curettage for pathological examination.

VII. Uterine inversion. The inverted uterus resembles a pedunculated submucous fibroid prolapsed into the vagina. Chronic inversion may cause increased vaginal discharge and hypermenorrhea. However, during bimanual examination, apart from the mass in the vagina, no additional uterine body or tumor pedicle can be detected. A uterine probe cannot enter the uterine cavity. Sometimes, the openings of both fallopian tubes can be observed on the surface of the mass. Note that submucous fibroids attached to the uterine fundus often cause varying degrees of uterine inversion.

VIII. Uterine malformation. Double uterus or rudimentary horn uterus without vaginal or cervical malformation may be misdiagnosed as uterine fibroids. Malformed uteri generally do not present with hypermenorrhea. If a young patient has a firm mass beside the uterus resembling the shape of the uterus, uterine malformation should be considered. Uterine hysterosalpingography is often required for definitive diagnosis. Since the advent of B-ultrasound, uterine malformations are easier to diagnose. Even early pregnancy in a rudimentary horn uterus can be diagnosed before rupture.

IX. Old ectopic pregnancy. Old ectopic pregnancy combined with pelvic blood clots and adhesion to uterine appendages may be misdiagnosed as uterine fibroids. However, careful inquiry about a history of amenorrhea, acute abdominal pain, and recurrent abdominal pain episodes, combined with severe anemia, fullness and tenderness in the vaginal fornix, and a pelvic-abdominal mass inseparable from the uterus with indistinct borders and less firmness than fibroids, should raise suspicion of old ectopic pregnancy. In such cases, posterior vaginal fornix puncture can be performed, and if necessary, 10 ml of saline can be injected to aspirate old blood and small clots for easy differentiation. B-ultrasound imaging can also aid in differentiation.