| disease | Placental Abruption |

| alias | Placental Abruption |

Placental abruption refers to the partial or complete detachment of a normally positioned placenta from the uterine wall before the delivery of the fetus after 20 weeks of pregnancy or during childbirth. It is a severe complication in the advanced stages of pregnancy, characterized by sudden onset and rapid progression. Inadequate management can endanger the lives of both the mother and the baby. Domestic reports indicate an incidence rate of 4.6% to 21%, while international studies report rates ranging from 5.1% to 23.3%. The reported incidence varies depending on whether the placenta is carefully examined after childbirth. Some mild cases of placental abruption may present no obvious symptoms before labor, with the condition only detected postpartum upon finding blood clot impressions at the detachment site during placental examination. Such cases are often overlooked.

bubble_chart Etiology

The exact pathogenesis of placental abruption remains incompletely understood, and its occurrence may be associated with the following factors.

1. Vascular lesions: Pregnant women with placental abruption often have complications such as grade III pregnancy-induced hypertension, chronic hypertension, and chronic kidney disease, particularly those with pre-existing systemic vascular lesions. When the spiral arteries in the decidua basalis undergo spasm or sclerosis, it leads to ischemia, necrosis, and rupture of distal capillaries, causing hemorrhage. Blood then flows into the decidua basalis layer, forming a hematoma that results in placental separation from the uterine wall.

2. Mechanical factors: Trauma (especially direct abdominal impact or falls where the abdomen hits the ground), external cephalic version to correct fetal position, a short umbilical cord or cord around the neck, and descent of the fetal presenting part during childbirth may all contribute to placental abruption. Additionally, rapid delivery of the first twin in a twin pregnancy or rapid outflow of amniotic fluid during membrane rupture in polyhydramnios can cause a sudden drop in intrauterine pressure and abrupt uterine contraction, leading to placental separation from the uterine wall.

3. Sudden increase in uterine venous pressure: In the advanced stages of pregnancy or during labor, prolonged supine positioning in pregnant women can lead to supine hypotensive syndrome. In this condition, the enlarged pregnant uterus compresses the inferior vena cava, reducing venous return to the heart and causing a drop in blood pressure. Meanwhile, uterine veins become congested, increasing venous pressure, which may result in stasis or rupture of the decidual venous bed, leading to partial or complete placental separation from the uterine wall.bubble_chart Pathological Changes

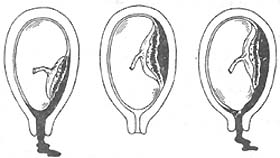

Placental abruption is classified into three types: revealed abruption, concealed abruption, and mixed hemorrhage (Figure 1). The main pathological change in placental abruption is hemorrhage in the decidua basalis, forming a hematoma that causes the placenta to detach from its attachment site. If the detachment area is small, the blood clots quickly, and there are usually no clinical symptoms. If the detachment area is large, continued bleeding forms a retroplacental hematoma, causing the detached portion of the placenta to expand further and the bleeding to increase gradually. When the blood breaks through the placental edge and flows outward between the fetal membranes and the uterine wall through the cervical canal, it is called revealed abruption or external hemorrhage. If the placental edge remains attached to the uterine wall, or the fetal membranes and uterine wall are not separated, or the fetal head is already fixed at the pelvic inlet, the blood behind the placenta cannot flow outward and accumulates between the placenta and the uterine wall, resulting in concealed abruption or internal hemorrhage. Since the blood cannot escape, the retroplacental hematoma grows larger, and the uterine fundus rises accordingly. When internal bleeding is excessive, the blood may still break through the placental edge and fetal membranes, flowing outward through the cervical canal, resulting in mixed hemorrhage. Occasionally, bleeding may rupture the amniotic membrane and spill into the amniotic fluid, turning it bloody.

(1) Revealed abruption (2) Concealed abruption (3) Mixed hemorrhage

Figure 1 Types of placental abruption

During internal hemorrhage in placental abruption, blood accumulates between the placenta and the uterine wall. As the local pressure gradually increases, the blood infiltrates the uterine muscle layer, causing muscle fiber separation, or even rupture and degeneration. When the blood reaches the uterine serosal layer, the uterine surface shows blue-purple ecchymosis, especially at the placental attachment site, a condition known as uteroplacental apoplexy. At this stage, the muscle fibers, soaked in blood, weaken in contractility. Sometimes, blood may infiltrate the broad ligament and the mesosalpinx, or even flow into the abdominal cavity through the fallopian tubes.

Severe placental abruption may lead to coagulation dysfunction, primarily due to the release of large amounts of tissue thromboplastin (Factor III) from the placental villi and decidua at the detachment site into the maternal circulation, activating the coagulation system and causing disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Microthrombi may also form in the capillaries of organs such as the lungs and kidneys, leading to organ damage. The longer placental abruption persists, the more procoagulant substances enter the maternal circulation, and DIC continues to progress, activating the fibrinolytic system and producing large amounts of fibrin degradation products (FDP). High levels of FDP have complex anticoagulant effects, interfering with the thrombin/fibrinogen reaction, fibrin polymerization, and inhibiting platelet function. Due to placental abruption, coagulation factors (including fibrinogen, platelets, and Factors V and VIII) are extensively consumed, and high concentrations of FDP are produced, ultimately leading to coagulation dysfunction.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations1. Mild type: Mainly characterized by external bleeding, the placental detachment area usually does not exceed one-third of the placenta, and it is more common during childbirth. The main symptoms are vaginal bleeding, which is generally copious, dark red in color, and may be accompanied by grade I abdominal pain or insignificant abdominal pain, with no marked signs of anemia. If it occurs during childbirth, the labor progresses more rapidly. Abdominal examination reveals a soft uterus, intermittent contractions, uterine size consistent with the weeks of pregnancy, clear fetal position, and mostly normal fetal heart rate. If bleeding is excessive, the fetal heart rate may change, with insignificant tenderness or only grade I localized tenderness (at the site of placental abruption). Postpartum examination of the placenta may show blood clots and indentations on the maternal surface. Sometimes, symptoms and signs are not obvious, and placental abruption is only discovered during postpartum examination when blood clots and indentations are found on the maternal surface of the placenta.

2. Severe type: Mainly characterized by internal bleeding, the placental detachment area exceeds one-third of the placenta, accompanied by a large retroplacental hematoma, and is more common in grade III pregnancy-induced hypertension. The main symptoms are sudden, persistent abdominal pain and/or lumbar soreness or lumbago, the severity of which varies depending on the size of the detachment area and the amount of retroplacental blood accumulation—the more blood, the more intense the pain. In severe cases, nausea, vomiting, pale complexion, sweating, weak pulse, and a drop in blood pressure may occur, indicating shock. There may be no vaginal bleeding or only a small amount, and the degree of anemia does not correspond to the amount of external bleeding. Abdominal examination reveals a uterus that is hard as a board upon palpation, with tenderness, especially pronounced at the placental attachment site. If the placenta is attached to the posterior wall of the uterus, uterine tenderness is often not obvious. The uterus is larger than the expected size for the weeks of pregnancy, and as the retroplacental hematoma continues to grow, the uterine fundus rises, and tenderness becomes more pronounced. Occasional contractions may be observed, with the uterus in a hypertonic state and unable to relax well during intervals, making it difficult to determine the fetal position. If the placental detachment area exceeds half or more of the placenta, the fetus often dies due to severe hypoxia, so the fetal heartbeat is usually absent in severe cases.

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

1. B-mode ultrasound examination For suspected and mild cases, a B-mode ultrasound examination can determine the presence of placental abruption and estimate the size of the detachment. If there is a retroplacental hematoma, the ultrasound image will show a hypoechoic area between the placenta and the uterine wall, with unclear boundaries. This is particularly helpful for suspected and mild cases. In severe cases, the B-mode ultrasound image is more pronounced: in addition to the hypoechoic area between the placenta and the uterine wall, there may also be reflective spots within the dark area (indicating organized hematoma), bulging of the placental chorionic plate into the amniotic cavity, and the fetal status (presence or absence of fetal movement and heartbeat).

2. Laboratory tests These primarily assess the patient's degree of anemia and coagulation function. A complete blood count evaluates the severity of anemia, while a urinalysis assesses renal function. Since placental abruption is often caused by grade III hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, additional tests such as blood urea nitrogen, uric acid, and carbon dioxide combining power may be necessary when indicated.

Severe placental abruption may complicate with DIC, requiring relevant laboratory tests, including DIC screening tests (such as platelet count, prothrombin time, fibrinogen level, and 3P test) and fibrinolysis confirmation tests (such as Fi test, i.e., FDP immunoassay, thrombin time, and euglobulin lysis time). For emergency cases, platelet count and whole blood clot observation and dissolution tests can serve as simple coagulation function monitoring to promptly diagnose potential coagulation disorders.

Whole blood clot observation and dissolution test: Take 2–5 ml of blood into a small test tube and tilt the tube. If the blood does not clot within 6 minutes, or if the clot dissolves within 1 hour, it suggests coagulation abnormalities. If the blood clots within 6 minutes, the fibrinogen level in the body is typically above 1.5 g/L; if clotting takes longer than 6 minutes and the clot is unstable, the fibrinogen level is usually between 1–1.5 g/L; if the blood fails to clot after 30 minutes, the fibrinogen level is typically less than 1 g/L.

The diagnosis is primarily based on medical history, clinical symptoms, and characteristic signs. For mild placental abruption, the symptoms and signs are often not typical, making diagnosis somewhat challenging. Careful observation and analysis are required, along with B-ultrasound examination for confirmation. In contrast, severe placental abruption presents with more typical symptoms and signs, making diagnosis relatively straightforward. When confirming severe placental abruption, it is also essential to assess its severity. If necessary, laboratory tests should be conducted to determine complications such as coagulation disorders and renal failure, ensuring the development of an appropriate treatment plan.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

1. Correcting Shock For patients admitted in critical condition with shock, active blood volume replenishment and shock correction should be performed to improve the patient's condition as soon as possible. Blood transfusion must be timely, and fresh blood is preferred, as it can both replenish blood volume and provide clotting factors.

2. Prompt Termination of Pregnancy Placental abruption endangers the lives of both the mother and the fetus. The prognosis for both is closely related to the timeliness of treatment. Before the fetus is delivered, the placenta may continue to detach, making it difficult to control bleeding. The longer the condition persists, the more severe it becomes, and the higher the likelihood of complications such as coagulation disorders. Therefore, once diagnosed, pregnancy must be terminated promptly. The method of termination depends on factors such as parity, the severity of the abruption, the fetal condition, and cervical dilation.

(1) Vaginal Delivery: For multiparous women in generally good condition, with predominantly visible bleeding and cervical dilation, and if rapid delivery is anticipated, vaginal delivery may be performed. Artificial rupture of membranes is done first to allow slow drainage of amniotic fluid, reducing uterine volume. After membrane rupture, an abdominal binder is applied to compress the placenta and prevent further detachment, while also promoting uterine contractions. Oxytocin infusion may be used if necessary to shorten labor. During delivery, closely monitor the patient's blood pressure, pulse, fundal height, uterine contractions, and fetal heart rate. Fetal electronic monitoring, if available, can detect abnormalities in contractions and fetal heart rate earlier.

(2) Cesarean Section: Indications for cesarean section include severe placental abruption, especially in primiparous women who cannot deliver quickly; mild abruption with signs of fetal distress requiring urgent intervention; severe abruption with fetal demise and deteriorating maternal condition; or lack of progress in labor after membrane rupture. During the procedure, after the fetus and placenta are delivered, oxytocics should be administered intramuscularly, and uterine massage should be performed to ensure good uterine contraction and control bleeding. If uterine apoplexy is found, aggressive measures such as oxytocic injections and massage can often improve contractions and control bleeding. If the uterus remains atonic with heavy, non-clotting bleeding, a hysterectomy should be performed while transfusing fresh blood.

3. Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage Patients with placental abruption are prone to postpartum hemorrhage, so oxytocics such as oxytocin or ergometrine should be administered promptly after delivery, along with uterine massage. If bleeding remains uncontrolled despite these measures and uterine contraction is poor, a hysterectomy should be performed without delay. If massive bleeding occurs without clot formation, coagulation disorders should be suspected and managed accordingly.

4. Management of Coagulation Disorders

(1) Fresh Blood Transfusion: Timely and sufficient fresh blood transfusion is an effective measure to replenish blood volume and clotting factors. Stored blood older than 4 hours has impaired platelet function and is less effective. Platelet concentrates may be transfused if thrombocytopenia is present.

(2) Fibrinogen Transfusion: If fibrinogen levels are low with active bleeding and non-clotting blood, and fresh blood transfusion is ineffective, 3g of fibrinogen dissolved in 100ml of sterile water can be administered intravenously. Typically, 3–6g of fibrinogen yields good results, with every 4g increasing plasma fibrinogen by 1g/L.

(3) Fresh Frozen Plasma Transfusion: Fresh frozen plasma is the next best option after fresh blood. Although lacking red blood cells, it contains clotting factors. One liter of fresh frozen plasma typically contains 3g of fibrinogen and can elevate factors V and VIII to minimally effective levels. Thus, it can be used as an emergency measure when fresh blood is unavailable. {|108|}

(4) Heparin: Heparin has a strong anticoagulant effect and is suitable for the hypercoagulable stage of DIC and cases where the disease cause cannot be directly eliminated. The management of DIC in patients with placental abruption primarily involves terminating the pregnancy to prevent further entry of thromboplastin into the bloodstream. For patients in the active bleeding phase with coagulation disorders, the use of heparin may exacerbate bleeding; therefore, heparin therapy is generally not recommended.

(5) Antifibrinolytic agents: Drugs such as 6-aminocaproic acid can inhibit the activity of the fibrinolytic system. If there is still ongoing intravascular coagulation, the use of such drugs may exacerbate intravascular coagulation and should therefore be avoided. However, if the disease cause has been eliminated and DIC is in the hyperfibrinolysis stage with persistent bleeding, these agents can be administered. For example, 6-aminocaproic acid (4–6g), tranexamic acid (0.25–0.5g), or p-aminomethylbenzoic acid (0.1–0.2g) can be dissolved in 100ml of 5% glucose solution for intravenous drip.

5. Prevention of renal failure: During treatment, urine output should be closely monitored. If hourly urine output is less than 30ml, blood volume should be replenished promptly. If urine output is less than 17ml or anuria occurs, the possibility of renal failure should be considered. In such cases, 250ml of 20% mannitol can be administered via rapid intravenous drip, or 40mg of furosemide can be given intravenously, with repeat doses if necessary. Most cases can recover within 1–2 days. If urine output does not increase shortly after treatment, and there is a significant rise in blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, potassium, etc., along with a decrease in CO2 combining power, it indicates severe renal failure and the onset of uremia. In this situation, dialysis therapy should be initiated to save the patient's life.

Strengthen prenatal examinations and actively prevent and treat pregnancy-induced hypertension; enhance management for high-risk pregnancies complicated by conditions such as hypertension or chronic nephritis; avoid supine position and abdominal trauma in the advanced stage of pregnancy; perform external cephalic version for abnormal fetal positions gently; prevent sudden drops in intrauterine pressure when managing polyhydramnios or twin childbirth.

1. DIC and Coagulation Dysfunction In cases of severe placental abruption, especially when intrauterine fetal death occurs, DIC and coagulation dysfunction may develop. Clinical manifestations include bleeding from subcutaneous tissues, mucous membranes, or injection sites, non-clotting or only loosely formed clots in uterine bleeding, and sometimes hematuria, hemoptysis, and hematemesis. Patients with placental abruption should be closely monitored from admission to postpartum, with attention to the occurrence of DIC and coagulation dysfunction based on laboratory results, and active prevention and treatment should be provided.

2. Postpartum Metrorrhagia Due to the impact of placental abruption on the uterine myometrium and the coagulation dysfunction caused by DIC, the likelihood of postpartum metrorrhagia is high and severe. Vigilance is essential.

3. Acute Renal Failure Most cases of severe placental abruption are accompanied by pregnancy-induced hypertension. Combined with excessive blood loss, prolonged shock, and DIC, these factors severely impair renal blood flow, leading to ischemic necrosis of the bilateral renal cortex or renal tubules and resulting in acute renal failure.

In the advanced stage of pregnancy, bleeding can be caused by conditions other than placental abruption, including placenta previa, uterine rupture, and cervical lesions. Differential diagnosis is essential, particularly distinguishing between placenta previa and uterine rupture.

1. Placenta previa: Mild placental abruption may also present as painless vaginal bleeding with nonspecific signs. Diagnosis can be confirmed by B-ultrasound to determine the lower edge of the placenta. Placental abruption in the posterior uterine wall may have inconspicuous abdominal signs, making it difficult to differentiate from placenta previa, but B-ultrasound can aid in identification. Severe placental abruption typically presents with classic clinical manifestations, making it easier to distinguish from placenta previa.

2. Threatened uterine rupture: This often occurs during childbirth and is characterized by strong uterine contractions, lower abdominal pain with guarding, dysphoria, slight vaginal bleeding, and signs of fetal distress. These clinical manifestations can be challenging to differentiate from severe placental abruption. However, threatened uterine rupture is often associated with cephalopelvic disproportion, obstructed labor, or a history of cesarean section. Examination may reveal a pathological retraction ring in the uterus, and catheterization may show gross hematuria. In contrast, placental abruption is commonly seen in patients with grade III hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and the uterus may feel board-like on examination.