| disease | Hiatal Hernia (Surgery) |

| alias | Hiatal Hernias |

The esophagus passes through the posterior mediastinum and enters the abdominal cavity via an opening in the posterior part of the diaphragm, known as the esophageal hiatus. When the gastric cardia, the abdominal segment of the esophagus, or other abdominal organs protrude into the thoracic cavity through this hiatus or its adjacent areas, it is referred to as a hiatal hernia. Hiatal hernias and reflux esophagitis can coexist or occur separately. Recognizing and distinguishing between these two conditions is crucial in clinical practice.

bubble_chart Etiology

The disease cause of hiatal hernia formation remains controversial. A small number of patients who develop the condition in early childhood have congenital developmental abnormalities, leading to a larger esophageal hiatus and weakened surrounding tissues. In recent years, acquired factors are widely considered to be the primary cause, associated with obesity and chronic increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

The physiological role of the esophagogastric junction remains poorly understood. When the esophagogastric junction functions properly, it acts as a valve, allowing liquids or solids to pass into the stomach without reflux, with only minimal reflux occurring during belching or vomiting. The factors ensuring this normal function include: ① the constrictive effect of the diaphragm on the esophagus; ② the role of the mucosal folds at the esophagogastric junction; ③ the acute anatomical angle formed between the esophagus and the gastric fundus; ④ the participation of the intra-abdominal esophageal segment in the lower esophageal valve mechanism; and ⑤ the action of the lower esophageal sphincter in the physiological high-pressure zone.

Most researchers consider the fifth factor listed above to be the primary mechanism preventing reflux, with the normal anatomical relationships in the vicinity providing supportive effects. The anti-reflux function is regulated by the vagus nerve; this function disappears after vagotomy. When intragastric pressure increases, gastric fluid is more likely to reflux into the esophagus.The squamous epithelial cells of the esophageal mucosa are not resistant to gastric acid. Prolonged exposure to refluxed gastric acid can lead to reflux esophagitis. In mild cases, mucosal edema and congestion occur, while in severe cases, superficial ulcers form, appearing as scattered spots or merging into patches. The submucosal tissue becomes edematous, and the damaged mucosa may be covered by a pseudomembrane, making it more prone to bleeding. The inflammation can penetrate the muscular layer and the fibrous outer membrane, even extending to the mediastinum, causing tissue thickening, increased fragility, and enlargement of nearby lymph nodes. In the late stage [third stage], fibrosis and cicatricial stenosis occur in the esophageal wall, leading to shortening of the esophagus. In some cases, the phrenoesophageal membrane may be stretched below the aortic arch, reaching the level of the ninth thoracic vertebra.

The severity of reflux esophagitis can vary depending on the following factors: the volume of gastric fluid reflux, the acidity of the refluxate, the duration of exposure, and individual resistance differences. Most pathological changes in reflux esophagitis are reversible, and mucosal lesions may heal after correction of hiatal hernia.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Larger sliding hiatal hernias can be detected during barium meal examinations even when the patient is at rest, showing a gastric pouch >3 cm protruding into the thoracic cavity, often accompanied by varying degrees of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. During surgery, it is observed that in these cases, the phrenoesophageal membrane inserts into the esophageal wall closer to the esophagogastric junction than in normal individuals. Whether this low insertion is congenital or acquired remains unclear.

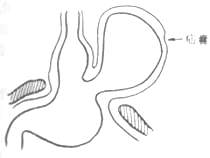

This hernia is less common, accounting for about 2% of all hiatal hernias, but it has significant clinical implications due to the herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity. In this hernia, the phrenoesophageal membrane has a defect, usually located on the left anterior side of the hiatus, and occasionally on the right posterior side. Due to this defect, the abdominal membrane can protrude through it, forming a true hernial sac, and the adjacent stomach may also herniate into the thoracic cavity through this fascial defect (Figure 4). Since the phrenoesophageal membrane cannot long restrain the upwardly displaced stomach, and the thoracic pressure is intermittently lower than the abdominal pressure, this defect inevitably enlarges progressively. In the late stage (third stage), the entire stomach may herniate into the thoracic cavity, with the cardia still partially fixed in place by the phrenoesophageal membrane, while the pylorus moves closer to it. The stomach may undergo rotation, torsion, obstruction, or stricture, and the thoracic stomach may dilate and rupture. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, any of these complications can lead to death (Figure 5). For these reasons, even asymptomatic paraesophageal hernias should be considered for early surgical intervention.

Figure 4 Paraesophageal hernia

Figure 5 Paraesophageal hernia with the entire stomach herniated into the thoracic cavity

As type II hernias enlarge, the phrenoesophageal membrane typically thins, and the distended stomach undergoes continuous deformation, pulling the gastric cardia upward. Once the cardia herniates through the esophageal hiatus and reaches above the diaphragm, it is termed a mixed hiatal hernia (type III) (Figure 6). Some suggest that when multiple abdominal organs, such as the colon or small intestine, enter the paraesophageal hernial sac simultaneously, it should be called a multi-organ hiatal hernia (type IV).

Figure 6 Mixed hiatal hernia

Hiatal hernias are more common in older males, and their clinical symptoms arise from gastroesophageal reflux or hernia complications. Sliding hiatal hernias (type I) rarely cause symptoms unless pathological reflux is present. Paraesophageal hernias can cause symptoms without reflux, as the symptoms stem from complications. The clinical manifestations of paraesophageal hernias vary depending on the herniated contents, but common features include premature satiety during meals, vomiting after large meals, upper abdominal discomfort, dysphagia, and thoracic gurgling sounds. Dysphagia results from external compression of the esophagus by the herniated organs. Herniated organs in the thoracic cavity compress the lungs and occupy part of the thoracic space, leading to postprandial cough and dyspnea. If complications such as obstruction, strangulation, necrosis, or perforation occur, the patient may experience shock and gastrointestinal obstruction symptoms, which can be fatal in severe cases.

Gastroesophageal reflux manifests as retrosternal discomfort and acid regurgitation, with the discomfort ranging from below the xiphoid process to the throat, accompanied by a burning sensation in severe cases. Symptoms may worsen during play, weightlifting, or straining during defecation, and can be relieved by eating or taking antacids.

The sensation of upper abdominal pain is often atypical and may be caused by acute esophageal spasm. The nature of the pain is similar to that of peptic gastric and duodenal ulcers, biliary colic, or cardiac colic, so careful differentiation is required. The pain from hiatal hernia radiates to the lower back and even to the upper limbs and jaw, can be triggered by swallowing, and is aggravated by hot drinks or alcohol. If cardiac colic cannot be ruled out, the patient should be admitted to the monitoring room for further examination. Gastric acid reflux can also cause pharyngeal pain, a burning sensation in the mouth, and even vocal cord irritation leading to hoarseness.

Dysphagia is a common symptom of gastric acid reflux. In some patients without esophagitis, dysphagia may be caused by varying degrees of esophageal spasm or poor esophageal contraction. In patients with esophagitis, when significant narrowing develops, dysphagia is only noticed when eating hard foods, while consuming hot foods, cold drinks, or alcohol can worsen heartburn. As esophageal narrowing worsens, less gastric acid refluxes into the esophagus, and heartburn gradually diminishes. Dysphagia caused by diffuse esophageal spasm differs from that caused by narrowing—the former is paroxysmal, occurring with both solid and liquid foods. In cases of motility disorders, difficulty swallowing or the sensation of a lump in the neck due to gastric acid reflux is often misdiagnosed as globus hystericus. A few patients experience such severe dysphagia that they cannot even swallow water due to food obstruction in the esophagus.

Aspiration caused by gastric acid reflux is common in patients with a nocturnal supine reflux pattern, often forcing the patient to wake up due to coughing from aspiration. Severe aspiration can lead to lung abscesses, recurrent pneumonia, and bronchiectasis. Morning hoarseness is another symptom of nocturnal aspiration. Gastric acid reflux occasionally triggers asthma, though this remains controversial. However, an asthma patient may experience more frequent attacks due to gastric acid reflux.

Bleeding from reflux esophagitis is uncommon. In ulcerative esophagitis, bleeding can be chronic and minor, with positive fecal occult blood leading to anemia, or it can be acute and massive, presenting with hematemesis or melena, resulting in hemorrhagic shock. The cause of melena is often due to bleeding from diffuse esophageal ulcers or penetrating ulcers in the gastric mucosal lining of the distal esophagus. These patients urgently require surgical treatment.

Patients with reflux esophagitis often experience bloating and belching, caused by the patient swallowing air repeatedly to counteract reflux.

In children, reflux symptoms are often subtle, possibly because they are unfamiliar with or unable to accurately describe them. However, hiatal hernia with reflux esophagitis in children often leads to growth retardation, chronic anemia, and recurrent pulmonary infections as complications.

When a patient presents to the clinic with typical symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation, or atypical symptoms like a foreign body sensation in the throat, hoarseness, globus pharyngeus, water brash, chest pain, paroxysmal cough, asthma, aspiration pneumonia, and other non-ulcer dyspeptic symptoms, the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis should be considered. If symptoms are relieved with antacid treatment, the diagnosis can generally be confirmed. To verify the diagnosis, an esophageal endoscopy and 24-hour pH monitoring should be performed.

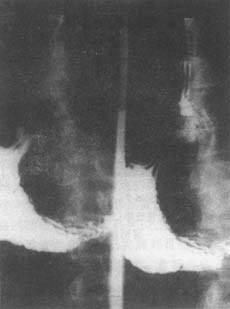

X-ray examination: Endoscopy is the primary method for diagnosing hiatal hernia. Barium meal examination is the most commonly used, but manual techniques are required to reveal the hernia. With the patient in the left lateral decubitus position and head lowered, after the stomach is filled with barium, abdominal pressure is applied while the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver. Signs of hiatal hernia may then appear: the subdiaphragmatic esophageal segment (abdominal segment) becomes shorter and wider or disappears, the cardia appears tented upward, a gastric pouch may be seen above the diaphragm (Figures 1 and 2), and an esophageal-gastric narrowing ring (Schatzki ring) may appear above the diaphragm, corresponding to the squamocolumnar junction (Figure 3). In cases of esophageal stenosis, the mucosal lining becomes deformed, and the lumen narrows. In cases of short esophagus, a thickened gastric mucosa may be seen above the diaphragm, and the esophagogastric junction may rise to the level of the 9th thoracic vertebra due to scar contraction. During barium meal examination, the Müller maneuver (closing the glottis after exhalation and then forcefully inhaling to increase intrathoracic negative pressure, promoting reflux of barium into the esophagus) is relatively effective for stimulating reflux. Some use the "water-drinking" method: having the patient drink water to mix with the barium in the stomach, followed by abdominal compression. In well-equipped hospitals, upper gastrointestinal contrast studies should be recorded for repeated review. Many believe that the presence of a hiatal hernia does not necessarily correlate with radiographic signs of reflux, and vice versa. There is no consensus on whether tenting alone should diagnose a hiatal hernia. The normal esophageal ampulla should not be mistaken for a hiatal hernia. Diffuse esophageal spasm can present with hiatal hernia and gastric fluid reflux signs. Scleroderma and achalasia, which lack esophageal peristalsis, must also be differentiated from hiatal hernia. If mechanical narrowing of the esophagus is observed, multiple perspectives should be examined to distinguish between neoplasms, ulcerative benign strictures, or esophageal motility disorders. Generally, radiologists' reports on the cause of narrowing should only serve as a reference for diagnosis, and histological confirmation is necessary for each patient.

Figure 1: X-ray of hiatal hernia

Barium contrast: Gastric mucosa appears tented

Figure 2: X-ray of hiatal hernia

Barium contrast: Gastric pouch seen above the diaphragm

Figure 3: Hiatal hernia

X-ray barium meal: Schatzki ring displaced upward, gastric mucosa tented

Endoscopy is the second most common method for diagnosing hiatal hernia after radiological examination. Fiberoptic gastroscopy is safer and less painful than rigid metal tube endoscopy, and it allows simultaneous examination of the stomach and duodenum to rule out factors that may elevate gastric pressure. It can also be used repeatedly and is convenient for examinations. In cases of hiatal hernia, the lower esophageal sphincter appears relaxed and remains open during both exhalation and inhalation. Normally, the esophagogastric junction descends during inhalation, but in the presence of a hernia, it does not shift, and the level of gastric fluid observed through the esophagoscope is higher than usual. In cases of reflux esophagitis, gastroscopy can reveal erythema, the number, depth, and arrangement of ulcers, ulcer bleeding, mucosal erosion, and stenosis. If the cardia remains open throughout the respiratory cycle, this is another indicator of reflux. If the patient's main complaint is dysphagia, the "T" maneuver can be used to observe the cardia from below, potentially ruling out the presence of early-stage cancer in this area before withdrawing the gastroscope to the esophagus. Careful, step-by-step examination is crucial. If esophageal stricture, severe esophagitis, or suspected Barrett's columnar epithelium is found, multiple biopsies should be performed, as esophageal ulcers can also undergo malignant transformation. When cancer cannot be ruled out, a rigid metal endoscope should be used for deep biopsies to confirm the diagnosis.

In certain cases of esophageal stricture, further diagnosis and observation of the efficacy of dilation can be achieved during the initial endoscopic examination. If reflux is suspected, or if a hiatal hernia is found without reflux symptoms and no signs of reflux are observed on radiographic imaging, esophageal function tests should be considered. When the patient's chief complaint is dysphagia, barium swallow and endoscopy are superior to esophageal function tests. If dysphagia is not a primary symptom and the barium swallow results are negative, esophageal function tests should be prioritized to establish a diagnosis, potentially avoiding the need for endoscopy.

Esophageal function tests can be performed on an outpatient basis and include esophageal manometry, standard acid reflux testing, acid clearance testing using a pH electrode placed in the esophagus, and acid perfusion testing. For more complex cases, hospitalization for prolonged 24-hour pH monitoring and continuous manometry may provide additional diagnostic information.

Esophageal Manometry: Simultaneous measurement of intraluminal pressure at different levels of the esophagus provides parameters for esophageal motility. In recent years, domestically developed multi-channel micro-balloon manometry has proven to be simpler, safer, and reusable. In cases of esophagitis, the lower esophageal segment exhibits reduced peristaltic amplitude, absence of peristalsis, or abnormal contractions. Normally, the high-pressure zone measures 2.67 kPa (20 mmHg); if it falls below 1.33 kPa (10 mmHg), gastric fluid reflux is more likely. Pressure measurements can also help differentiate atypical pain caused by myocardial infarction or biliary diseases.

Standard Acid Reflux Test: Inject 150–300 mL of 0.1 mol/L HCl into the stomach and slowly withdraw the electrode, which is positioned 5 cm above the lower esophageal high-pressure zone. Measure the pH at 5, 10, and 15 cm intervals. The test is combined with the Valsalva maneuver (forced exhalation against a closed glottis to increase intrathoracic pressure) and the Müller maneuver (forced inhalation against a closed glottis after exhalation to increase negative intrathoracic pressure and change body position) to induce gastroesophageal reflux. A pH < 4 lasting more than 5 minutes is considered positive. This test is particularly helpful when other clinical diagnostic methods are inconclusive. Normally, gastric pH ranges from 1 to 4, while the esophageal high-pressure zone pH is 5 to 7. If a pH electrode measures a transition from pH 2–2.4 in the stomach to 6.5–7.0 within 2 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter, it indicates normal cardia function.

Acid Clearance Test: The pH electrode remains positioned 5 cm above the high-pressure zone. Inject 15 mL of 0.1 mol/L HCl into the mid-esophagus via a proximal catheter. The patient is instructed to swallow every 30 seconds to clear the acid from the esophagus, and the number of swallows required for the pH to rise above 5 is recorded. Normally, this occurs within 10 swallows. This test does not confirm gastric reflux but reflects the severity of esophagitis.

Acid Perfusion Test: If reflux symptoms are unclear, this test may be used. The catheter remains in the mid-esophagus, with its proximal end placed behind the patient and connected via a Y-tube to two intravenous solution bottles—one containing 0.1 mol/L HCl and the other saline. Each solution is infused for about 10 minutes, and the patient's reactions are recorded by an observer. If acid perfusion reproduces spontaneous reflux symptoms while saline does not, a positive acid perfusion test suggests that the symptoms are due to acid reflux rather than esophageal motility disorders.

Long-term pH monitoring method: For patients who have undergone previous esophageal surgery, those with comorbid conditions, or those suspected of having reflux-induced aspiration pneumonia or "colicky pain," 24-hour continuous pH monitoring can provide valuable diagnostic information. After performing a series of standard esophageal function tests, the pH electrode is placed 5 cm above the high-pressure zone of the distal esophagus and connected to a strip-chart recorder via a pH meter. The patient's activities and symptoms are recorded over 24 hours. During this period, the patient eats normally but is restricted in fluid and food types to maintain a pH value >5. The number of reflux episodes can be quantified based on frequency and duration in both supine and upright positions. A pH value above 7 is classified as alkaline reflux. Currently, 24-hour pH monitoring is considered the most reliable and sensitive method for diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux. It allows continuous recording of esophageal pH changes over 10, 12, or 24 hours. Key parameters include: ① the number of times pH <4 occurs within 24 hours; ② the percentage of total time with pH <4; ③ the number of episodes where pH <4 lasts longer than 5 minutes; and ④ the longest acid exposure time. These measured values can be compared with those of healthy individuals to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux. The latest generation of 24-hour esophageal pH and pressure synchronous recording devices, which allow examination under completely normal physiological conditions, has now been developed and produced domestically.

In recent years, using ultrasound to examine the esophagogastric cardia and measure the length of the abdominal esophagus has proven more effective than barium meal X-ray examination in diagnosing smaller hiatal hernias.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for paraesophageal hernias can more clearly determine the nature of the herniated contents.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Most sliding hiatal hernias have mild symptoms, and mild or grade II esophagitis is common among Chinese patients. These patients should first undergo medical treatment, including taking antacids, dietary adjustments, avoiding activities that increase abdominal pressure, and adopting measures such as sleeping with a high pillow or lying on the left side. If reflux esophagitis has progressed to grade III, surgery should be considered to prevent esophageal stricture. Paraesophageal hernias should be treated surgically as early as possible, regardless of symptoms, and mixed hiatal hernias should also undergo surgical treatment to avoid complications such as gastric obstruction and strangulation.

Regarding the medical treatment of reflux esophagitis, antacids, alginates, or compound antacid formulations can alleviate symptoms and reduce inflammation. However, H2 receptor blockers are more commonly used due to their relatively confirmed efficacy. For severe cases, omeprazole (Losec) is superior to conventional doses of ranitidine. Although antacids provide short-term relief, they do not alter the natural course of the disease, and the recurrence rate is high after discontinuation. Therefore, hernia repair and anti-reflux surgery are ultimately required.

1. **Indications and Contraindications for Surgery** Surgical treatment for hiatal hernia primarily addresses the anatomical defect itself. Paraesophageal hernias, mixed hiatal hernias, and multi-organ hiatal hernias may lead to incarceration or strangulation of the gastric wall or other herniated abdominal organs. Due to the compression of the lungs by large herniated contents, surgery should be performed early even in the absence of obvious symptoms. Asymptomatic sliding hiatal hernias only require outpatient follow-up and do not necessitate surgery. Sliding hiatal hernias with reflux esophagitis should be considered for surgery if they progress to ulcerative esophagitis, esophageal stricture, bleeding, or recurrent pulmonary infections due to reflux. Regarding Barrett's esophagus, some advocate surgery to prevent cancer.

**Contraindications for surgery:** Acute infections, severe cardiopulmonary failure, liver or kidney dysfunction, and advanced-stage cancer patients are contraindicated for surgery. Hiatal hernias are more common in elderly males, and age itself is not a contraindication unless there are clear signs of frailty.

2. **Selection of Surgical Methods** Surgery for hiatal hernia and reflux esophagitis should include repairing the lax esophageal hiatus, lengthening and fixing the subdiaphragmatic esophageal segment, and reconstructing the anti-reflux valve mechanism.

There are various methods for treating reflux esophagitis and its complications, and the choice of surgery depends on the specific patient and the surgeon's expertise. Factors to consider before selecting a surgical approach include: whether thoracic or abdominal access is unfavorable; whether the patient has a history of anti-reflux surgery; whether esophageal resection or myotomy is needed; and the patient's constitution.

Surgical practice shows that for patients with extensive and severe esophagitis, a thoracic approach facilitates esophageal mobilization and fundoplication. Patients who have failed previous anti-reflux surgery due to inadequate esophageal mobilization should undergo a thoracic approach. In obese cases, a transabdominal incision provides better exposure and facilitates the management of associated pulmonary or mediastinal diseases. For patients with controlled esophagitis and mild obesity undergoing their first anti-reflux procedure, an abdominal approach may be used. If concurrent abdominal conditions requiring surgery are present, an abdominal approach is also suitable. Paraesophageal hernias are often repaired via thoracic or abdominal access.

Regarding sutures, absorbable and acid-resistant absorbable sutures were used in the past. Currently, most surgeons prefer non-absorbable sutures and atraumatic non-absorbable sutures.

Currently, surgical procedures for repairing sliding hiatal hernias and correcting gastroesophageal reflux include fundoplication, partial fundoplication, anatomical repair, and ligament flap repair.

(1) Fundoplication: In 1956, Nissen reported the fundoplication procedure and published its early results in 1963. In 1973, Rossetti reported his modified version of fundoplication. Nissen referred to his fundoplication as "valvuloplasty." The procedure involves completely wrapping the gastric fundus around the lower esophagus and suturing it to the lesser curvature on the right side of the esophagus. This creates a newly formed "collar" that transmits positive gastric pressure to the encircled esophagus, compressing it. The one-way valve function of this mechanism allows food to pass from the esophagus into the stomach but prevents reflux from the stomach back into the esophagus. Among 875 patients, symptoms disappeared postoperatively, with a surgical mortality rate of 0.6% and a recurrence rate of hernia and reflux esophagitis of approximately 1%. However, with longer follow-up periods, 10–20% of cases developed postoperative complications, including a syndrome where patients could not belch after swallowing air, leading to a sensation of pressure in the left upper abdomen or precordial region, especially after eating, which sometimes progressed to noticeable pain.

The Nissen procedure can also be performed via the left lower thoracic approach, which is most suitable for obese patients or those who have previously undergone failed hernia repair via the abdominal approach and require reoperation. It is particularly indicated for cases of short esophagus caused by extensive scarring and secondary spasms. Postoperative clinical observation, radiographic contrast studies, esophageal manometry, and pH monitoring data analysis confirm that the intrathoracic fundoplication also achieves effective valve formation and restores the resting pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter to normal values.

①Nissen Fundoplication (Transabdominal Approach): Preoperatively, improve the patient's nutritional status and correct typical edema and electrolyte imbalances. Prepare according to general anesthesia requirements. For patients with pulmonary diseases, administer antibiotics to control inflammation for two weeks before considering surgery. The patient is placed in a supine position with the spine elevated, and the procedure is performed under general anesthesia. A midline upper abdominal incision is made.

Surgical Steps: After incising the abdominal membrane, assess the extent of sliding hiatal hernia. Identify the course of the lower esophagus based on the direction of the large gastric tube placed preoperatively. Incise the triangular ligament of the liver and retract the left lobe medially. Transversely incise the abdominal membrane above the esophagogastric junction. Extend the incision, divide the left gastrophrenic ligament and its junction with the gastrosplenic ligament on the left side, and open the greater omental sac on the right side to separate the upper part of the hepatogastric ligament. Securely ligate any encountered branches of the left gastric artery, short gastric arteries, and phrenic arteries to prevent bleeding. Push the abdominal membrane, connective tissue, and phrenoesophageal membrane upward to free 4–6 cm of the lower esophagus, taking care to avoid injury to the vagus nerve. Pass an esophageal tape around the esophagogastric junction and retract it downward.

This maneuver should be performed with particular delicacy. Reflux esophagitis causes inflammatory edema in the posterior wall of the lower esophagus and surrounding tissues, making them fragile and severely adherent, prone to injury during dissection. The anterior wall is less affected and less likely to tear. To avoid injuring the less inflamed posterior wall, use the right index finger to palpate the pulsation of the abdominal aorta and the anterior surface of the thoracic vertebrae, and rely on the course of the gastric tube to accurately determine the relationship between the posterior esophageal wall and surrounding tissues. If there is no severe esophagitis, the posterior branch of the vagus nerve can also be separated to prevent it from being enclosed later. Pass the posterior wall of the gastric fundus from left to right behind the lower esophagus to the right side, ensuring that this posterior wall encloses only the esophagus and not the proximal stomach. The first suture passes through the anterior wall of the gastric fundus, the muscle layer and submucosa of the lower esophagus, and the posterior wall of the gastric fundus. Tighten this suture; if an index finger can pass between the fundoplication and the esophagus (containing the large gastric tube), the tension is appropriate, and the suture can be tied. Then place another suture below it, followed by two more sutures, none of which penetrate the esophageal wall. Recheck the tightness of the wrap. Some surgeons recommend passing all fundoplication sutures through the esophageal wall to prevent the lower esophagus from sliding within the wrap. To stabilize the fundoplication, secure it to the anterior gastric wall with 2–3 additional sutures. After closing the abdomen, remove the large gastric tube before extubation and replace it with a nasogastric tube for postoperative decompression. This procedure does not include narrowing the hiatus.

②Nissen Fundoplication (Transthoracic Approach): The patient is placed in the right lateral decubitus position, and under general anesthesia, a posterolateral incision is made through the left sixth intercostal space to enter the chest. Preoperatively, insert a large gastric tube through the nose into the stomach to aid in identifying the lower esophagus and prevent excessive tightness of the gastric fundus wrap around the lower esophagus.

Surgical steps; After entering the chest, the left lower pulmonary ligament is divided, and the mediastinal pleura on the left side of the esophagus is incised to expose and lift the lower segment of the esophagus using an esophageal tape. The esophagus is pulled upward and forward, and the pleura covering the hernial sac and hiatus is separated. Beneath the pleura, the phrenoesophageal ligament connects the endoabdominal fascia and endothoracic fascia, which is incised anterolaterally to push aside the peritoneal reflection and retroperitoneal fat, freeing the cardia from its attachments. The branches of the left gastric artery ascending lateral to the vagus nerve are ligated, and the cardia is pulled into the thoracic cavity. The branches of the left gastric artery within the upper part of the hepatogastric ligament are ligated, and the esophageal branches of the left gastric artery are separated while preserving the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve. On the left side, the short gastric arteries are dissected, ligated, and divided to completely mobilize the gastric fundus. The wrap is returned to the abdominal cavity to expose the two crura forming the hiatus. Generally, three interrupted sutures are sufficient to narrow the enlarged hiatus, and these sutures are left untied for later ligation. In cases of short esophagus, if it is difficult to place the wrap into the abdominal cavity, the three sutures between the two crura are ligated. The tightness of the gastric fundus wrap is rechecked. The mediastinal pleura is closed with continuous sutures, and a chest tube is placed in the left lower thorax. The chest is closed in layers. At the end of the procedure, a standard nasogastric tube replaces the large-bore gastric tube.

③Rossetti Modified Fundoplication: This modified fundoplication involves wrapping the anterior wall of the gastric fundus around the lower esophagus. Currently, most surgeons commonly use this modified technique as an alternative to the Nissen procedure. The advantage of using the anterior gastric wall for a limited fundoplication is the preservation of the lesser omentum and the posterior fixation of the proximal stomach. This technique also preserves the hepatic branches of the vagus nerve, and the intact posterior fixation ensures that the gastric body does not herniate into the fundic wrap. However, in cases where a selective proximal vagotomy has been previously performed, and the lesser omentum has been dissected or the stomach has been mobilized, only a Nissen fundoplication can be performed.

Surgical Steps: The patient is placed in the supine position, and an upper midline abdominal incision is made under general anesthesia. After entering the abdomen, the peritoneum covering the esophagogastric junction is incised transversely and extended to the left, dividing the gastrosplenic ligament and ligating the short gastric vessels to fully mobilize the gastric fundus. An esophageal tape is looped around the esophagus and gently retracted downward and outward. A portion of the anterior gastric wall is pulled behind the esophagus to the right side (only a 1 cm incision is made in the uppermost part of the hepatogastric ligament on the right side to preserve the hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerve; additionally, the posterior gastric wall is not separated from the peritoneal adhesions, usually only 1–2 cm). The anterior gastric wall can then be pushed behind the esophagus to the right side with a finger. Another fold is selected from the anterior gastric wall slightly distal to the greater curvature. If the fold is insufficient for wrapping, the greater curvature may be further mobilized. The two folded anterior gastric walls are approximated, ensuring the wrap is snug but allows passage of an index finger. Three interrupted sutures are placed in the anterior gastric walls without penetrating the gastric lumen, only through the seromuscular layer. A fourth suture is placed below the third suture, passing through the connective tissue at the junction of the serosa and muscularis. The anterior gastric wall is wrapped 360° around the abdominal esophagus. The lower edge of the wrap must be carefully checked against the anterior gastric wall. This modified technique does not involve narrowing the hiatus.

(2)Partial Fundoplication—180° Partial Fundoplication: Various 180° partial fundoplication techniques are still in use, differing based on whether the gastric fundus is fixed to the anterior or lateral aspect of the esophagus. Additionally, various measures are taken to reduce hiatal sliding and support the abdominal esophagus within the peritoneal cavity.

①180° Anterior Partial Fundoplication: The patient is placed supine, and under general anesthesia, an upper midline abdominal incision is made. After exploration, the peritoneum overlying the esophagogastric junction is incised transversely and extended to the left, dividing the gastrophrenic ligament up to the splenic ligament. The incision is not extended on the right side to preserve the hepatic branches of the vagus nerve. The phrenoesophageal membrane is bluntly dissected to expose slightly more than half the circumference of the abdominal esophagus. The vagus nerve remains on the anterior esophageal wall. An esophageal tape is looped around the esophagus and retracted downward and outward, mobilizing 4–6 cm of the lower esophagus. The next step involves narrowing the hiatus posteriorly to allow passage of the esophagus (with a large gastric tube) and an index finger. Some do not recommend this as a routine step, while others suggest narrowing the hiatus anteriorly for safety, as the diaphragm near the central tendon is thicker and sutures are less likely to tear. Three to four sutures are used to fix the 4–6 cm mobilized anterior gastric wall to the left side of the esophagus. The lowest suture passes through the peritoneal reflection of the cardia, and the highest suture passes through the edge of the hiatus. Another 3–4 sutures are placed to wrap the anterior gastric wall around the anterior esophagus and fix it to the right lateral esophageal wall, with the highest suture also passing through the hiatus edge and the lowest through the peritoneal reflection of the cardia. After removing the large gastric tube, the abdomen is closed without the need for drainage.

②180° Lateral Partial Fundoplication (Posterior Gastropexy): In 1961, Hill et al. proposed a technique to reinforce the lower esophageal sphincter during hernia repair. A 1967 report of 149 cases showed no mortality or hernia recurrence, with only 4 cases (3%) showing symptoms suggestive of unresolved or recurrent esophagitis. Postoperative manometry in most patients showed that the resting pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter was near or restored to normal levels.

The HILL procedure is performed via a transabdominal approach to reduce the hernia and mobilize the distal esophagus. The diaphragmatic crura are sutured posterior to the esophagus to narrow the enlarged hiatus; the anterior and posterior bundles of the phrenoesophageal tissue at the esophagogastric junction are fixed to the medial arcuate ligament anterior to the abdominal aorta. This method preserves a longer segment of the intra-abdominal esophagus, allowing it to be influenced by positive intra-abdominal pressure. Subsequently, gradual modifications were made: folding and suturing the inner edge of the gastric fundus to the left side of the abdominal esophagus (partial fundoplication of the lateral portion), to the right lateral wall of the abdominal esophagus (partial fundoplication of the anterior portion), and to the medial arcuate ligament (220° partial fundoplication). If the medial arcuate ligament is underdeveloped, the anterior wall of the gastric fundus is sutured to the medial edge of the hiatus, securing the abdominal esophagus in place.

③270° Partial Fundoplication: This procedure is commonly referred to as Type 4 (Mark IV) anti-reflux repair. In the early 1950s, Belsey designed three anti-reflux surgical procedures, all of which failed. The first procedure was similar to Allison's operation for correcting reflux, involving shortening and reattaching the phrenoesophageal membrane (ligament) to the esophageal wall. Mark II was a transitional procedure leading to the concept of wrapping the fundus around the esophagus. Mark III involved a three-layer folding suture between the fundus and the esophagus, covering 5–6 cm of the esophagus below the diaphragm, effectively preventing reflux but often resulting in postoperative dysphagia. The Mark IV repair eliminated the third row of folding sutures, allowing the wrapped abdominal segment of the esophagus to receive uniform pressure from the gastric wall, preventing reflux without excessively lengthening this segment and obstructing food passage. A unique feature of this procedure is its transthoracic approach, which involves hernia reduction, suturing the diaphragmatic crura posterior to the esophagus with three interrupted stitches to narrow the enlarged hiatus, and using two layers of mattress sutures (possibly with pledgets) to fold the fundus around the anterior and lateral aspects of the distal esophagus, aiming to preserve a 3–4 cm length. The distal esophagus remains below the diaphragm, enabling it to respond to gastric pressure and restoring the anti-reflux function of the lower esophageal sphincter. Since the fundus covers only 3/4 of the esophageal circumference, leaving 1/4 uncovered, the esophagus can expand to accommodate larger food boluses, reducing the incidence of postoperative dysphagia.

(3) Anatomical Repair of the Esophagogastric Junction: Anatomical repair includes hiatal plasty, fundopexy to the diaphragm, and the Lortat-Jacob anti-reflux procedure. These techniques aim to restore the normal anatomy of the esophagogastric junction and prevent hiatal hernia.

① Hiatal Plasty: This procedure involves pulling the hiatus via an abdominal approach without incising the peritoneal membrane covering the abdominal esophagus. The abdominal esophagus and hiatus are identified using a pre-inserted nasogastric tube. Two to three silk sutures are passed through the anterior edges of the hiatus. The surgeon inserts an index finger between the anterior edge of the hiatus and the esophagus, then tightens and ties the sutures. The ability to freely move the finger indicates appropriate tightness. This technique displaces the esophagus posteriorly while narrowing the hiatus anteriorly.

② Fundopexy to the Diaphragm: This procedure is suitable for patients with grade II–III gastroesophageal reflux who have not responded to six months of strict medical treatment, have a disease duration exceeding one year, and exhibit severe symptoms. Some hospitals still use this as the primary anti-reflux procedure, achieving satisfactory results in 80% of cases.

Preoperative Preparation: ① Upper gastrointestinal contrast imaging to evaluate the relationship between the stomach and adjacent organs and morphological changes at the esophagogastric junction. ② Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to assess the severity of reflux esophagitis and exclude other pathologies in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. ③ Esophageal manometry to record esophageal motility dysfunction and the extent of lower esophageal sphincter impairment. ④ pH monitoring to assess acid reflux-related changes in esophageal acidity. ⑤ Insertion of a large-bore gastric tube preoperatively.

Surgical Steps: The patient is placed in a supine position with the lumbar region elevated and the head higher than the feet. Under general anesthesia, a midline upper abdominal incision is made. The stomach is pulled downward, and the left lobe of the liver, spleen, and left colic flexure are retracted to fully expose the fundus and esophagogastric junction. The fundus is sutured to the abdominal surface of the diaphragm in an obliquely upward-left direction. The first suture is placed 0.5–1 cm from the abdominal esophagus, followed by four additional sutures spaced 1–2 cm apart. The sutures on the diaphragm are spaced slightly wider than those on the fundus to create tension by slightly stretching the fundic wall. Upon completion, the large-bore gastric tube is replaced with a standard decompression tube, and the abdomen is closed.

This procedure is relatively simple, but care must be taken to avoid injuring the esophagus and spleen. A minority of cases may develop diaphragmatic nerve irritation during or shortly after surgery, and some may experience pleural effusion. Approximately 6% of patients experience unresolved or recurrent reflux symptoms postoperatively. If medical treatment fails, reoperation may involve removing the fundopexy sutures and performing a fundoplication.

③Lortat-Jacob anti-reflux procedure: The patient is placed in a supine position under general anesthesia, and the abdomen is entered through a midline upper abdominal incision. The peritoneal membrane anterior to the abdominal segment of the esophagus is incised, and the esophagogastric junction is carefully dissected free, encircled with an esophageal tape, and pulled to the left anterior to expose the diaphragmatic crura. Three sutures are placed between the base and the left lateral wall of the abdominal esophagus to eliminate the hiatal defect; then, the gastric fundus is sutured and fixed to the diaphragm.

(4) Ligament flap repair: Using the patient's own tissue or artificial materials to reposition the hiatal hernia and fix it below the diaphragm. Due to poor efficacy, this method is rarely used nowadays.

① Greater omentum flap fixation: A vascularized strip of the left portion of the greater omentum is taken and wrapped around the esophagogastric junction to create a "scarf-like" structure, pulling the abdominal segment of the esophagus back into the abdominal cavity for internal fixation.

② Round ligament flap fixation: A 3 cm wide abdominal membrane is freed from the umbilicus to the xiphoid level. The round ligament of the liver and the falciform ligament flap are sutured to the medial side of the gastric fundus and to cover the abdominal segment of the esophagus.

(5) Angelchik anti-reflux ring: To prevent gastroesophageal reflux, a prosthetic silicone ring can be placed around the cardia. Its function is to buffer the increased gastric pressure, but its long-term efficacy is poor, and most experts do not recommend its use.

Surgical indications: Patients with grade III–IV esophagitis and high-risk factors; failure of fundoplication requiring corrective surgery. Surgical procedure: The cardia and the distal 3 cm of the esophagus are freed, carefully preserving the vagus nerve branches. The hiatal hernia is exposed and reduced without freeing the gastric fundus. The silicone ring is placed around the cardia and tied anteriorly. The tightness is checked manually, usually allowing the passage of one finger, without additional sutures. If symptoms recur postoperatively due to ring displacement, revision surgery is required. In cases of erosion, the anti-reflux ring must be removed and replaced with a modified fundoplication to cover the defect.

(6) Postoperative complications of fundoplication: If the fundoplication is too tight, it may obstruct food passage and cause "gas-bloat syndrome," characterized by restricted belching, abdominal distension and fullness, dysphagia, and epigastric discomfort or pain. Releasing an overly tight wrap is difficult, and repair is even more challenging. Therefore, intraoperative assessment of wrap tightness is crucial. Preoperatively, a balloon-equipped nasogastric tube can be placed across the cardia to measure and monitor lower esophageal sphincter pressure. The ideal pressure should be maintained at 5.33 kPa (40 mmHg). If pressure exceeds this, some sutures should be removed; if it is lower, additional sutures may be needed to reinforce the wrap.

Recurrence of symptoms after fundoplication is often due to suture loosening, unraveling, or tearing. Immediate reoperation is usually unnecessary, and medical treatment should be attempted first. If sutures completely loosen, leading to uncontrolled grade III–IV reflux esophagitis, surgical repair is required to tighten or rearrange the sutures. Alternatively, a prosthetic ring can be placed around the cardia.

If the wrap is too loose and fails to secure the anterior gastric wall, the cardia may slide upward out of the wrap, causing recurrent reflux symptoms ("telescoping" slippage). Surgical repair is difficult. Post-fundoplication, about 1–3% of cases develop gastric ulcers, primarily in the proximal stomach due to ischemia and mechanical trauma. These ulcers can appear as early as one week postoperatively and are easily diagnosed via barium studies. Early medical treatment is recommended. The Angelchik anti-reflux ring can also be used to stabilize the cardia.

(7) Evaluation of sliding hernia repair and anti-reflux surgery: Currently, anatomical repair procedures are less commonly used. After nearly 20 years of follow-up, only fundoplication and various partial fundoplication techniques have been objectively shown to alleviate pathological gastroesophageal reflux, with efficacy rates as high as 80-90%. The incidence of postoperative complications and mortality rates are almost identical, while measurements of spontaneous and stimulated acid reflux and lower esophageal sphincter pressure indicate that fundoplication is superior, with better anti-reflux effects compared to partial fundoplication. Compared to preoperative measurements, fundoplication can further increase lower esophageal sphincter pressure more effectively than partial fundoplication. There is no difference in the recurrence rate of reflux symptoms between the two surgical methods, but the recurrence rate increases with longer follow-up periods. Postoperative dysphagia, hiccups, and difficulty vomiting, as well as the "gas-bloat syndrome," are more common after fundoplication.

After years of clinical practice, the commonly used procedures for repairing sliding hiatal hernias and anti-reflux operations include the Belsey 270° fundoplication, Nissen fundoplication, and Hill procedure, all of which can restore the function of the lower esophageal sphincter. The Nissen procedure is more effective in controlling esophageal reflux and can be performed via either a thoracic or abdominal approach. The Belsey procedure is associated with fewer postoperative "gas-bloat syndrome" complications but can only be performed via a thoracic approach. The Hill procedure effectively controls gastroesophageal reflux with fewer postoperative complications, but it is limited to an abdominal approach and is unsuitable for simultaneously addressing other thoracic comorbidities. The primary advantage of the Belsey procedure is its suitability for patients with prior abdominal surgeries, those requiring concurrent management of other thoracic conditions, or patients with esophageal motility disorders, as it is less likely to cause lower esophageal obstruction postoperatively.

With advancements in endoscopic techniques, successful cases of laparoscopic fundoplication and partial fundoplication have been reported.

4. Paraesophageal Hernia Repair Paraesophageal hernias may persist for years, with patients experiencing only mild postprandial epigastric discomfort, nausea, and grade I dyspnea. However, since they result from anatomical defects and are difficult to treat medically, and due to their potential for life-threatening complications, surgical repair is recommended even in the absence of typical symptoms. Emergency surgery is required if complications such as incarcerated necrosis of gastrointestinal organs, massive bleeding, or obstruction occur.

(1) Treatment Principles and Surgical Approach Selection: The surgical principles for esophageal hernias are similar to those for general hernia repair, involving reduction of herniated contents into the abdomen, fixation within the abdominal cavity (to the abdominal wall or diaphragm), and suturing to narrow the enlarged hiatal opening. If necessary, the hernia sac should also be excised. For mixed-type hiatal hernias with gastroesophageal reflux, an anti-reflux procedure should be performed after hernia repair, tailored to the specifics of the sliding hiatal hernia. In cases of pure paraesophageal hernias, the lower esophageal sphincter and its fixation to the posterior mediastinum and diaphragm remain normal and should not be dissected, as this could lead to postoperative sliding hernias.

Paraesophageal hernias can be repaired via an abdominal or thoracic approach. The abdominal approach provides better exposure, facilitates thorough examination of reduced organs, allows fixation within the abdomen and narrowing of the hiatal opening, and enables management of concurrent conditions such as duodenal ulcers and gallbladder stones. The abdominal approach also permits detailed evaluation of the cardia. If the lower esophagus is found below the diaphragm but firmly fixed to the posterior mediastinum, a paraesophageal hernia (rather than a mixed-type hiatal hernia) can be confirmed. For large paraesophageal hernias with severe intrathoracic adhesions or associated short esophagus, a thoracic approach is preferred. To prevent postoperative recurrence or the formation of a serous membrane cyst in the thorax, the hernia sac should be excised whenever possible.

(2) Preoperative Preparation: Preoperative measures include antibiotic administration, maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, nutritional support, and placement of an 18-French nasogastric tube for continuous suction. Since part or all of the stomach may be herniated into the thorax, causing angulation and obstruction at the cardia, preoperative gastric decompression is often challenging, and precautions must be taken to prevent aspiration during anesthesia induction.

(3) Surgical Procedure: The patient is positioned supine or in the right lateral decubitus position under general anesthesia. An upper midline abdominal incision or a left 7th intercostal incision is used.

①Hernia reduction and hiatus repair; if the thoracic approach is used, after entering the chest, a detailed exploration should be conducted to check for the presence of intrathoracic inflammatory effusion and adhesions, as well as whether the organs in the hernia have perforation or necrosis. Strict measures must be taken to protect the thoracic cavity from contamination. After incising the hernial sac, identify whether the herniated contents are the stomach, colon, spleen, greater omentum, or small intestine. If it is the stomach, the form of its rotation or volvulus should be clearly recognized, and the herniated organs should be carefully reduced back into the abdomen. If difficulties are encountered, first perform aspiration to remove gastric contents or carry out a decompressive gastrostomy. At the end of the procedure, the stomach can be fixed to the anterior wall, which not only stabilizes the stomach but also prevents postoperative incarceration or strangulation of the gastrointestinal organs (stomach), leading to ulcer formation and adhesions. Extra care must be taken during dissection. Before reducing the herniated organs, the hernia ring must be enlarged, and a thorough examination must be performed to check for any organ damage. If necessary, perform resection, anastomosis, or repair. For gastric ulcers, if there is no prior history of ulcers, intraoperative gastroscopy with multiple biopsies should be considered to rule out malignancy.

After reducing the hernia, resect and suture the residual hernia sac as low as possible, then fix it to the edge of the hiatus with interrupted sutures. After freeing the edges of the hiatus, use interrupted non-absorbable sutures (with pledgets) to narrow the enlarged hiatus. Ensure it can accommodate a finger.

If an anti-reflux procedure is needed simultaneously, perform a Belsey or Nissen hernia repair after reducing the hernia and handling the sac. If using an abdominal approach, perform a Hill posterior gastropoxy or Nissen hernia repair.

② Gastropoxy: The Nissen gastropoxy is performed via an abdominal approach to repair paraesophageal hernias (where the herniated content is the stomach). After reducing the hernia contents, narrow the hiatus with 3–4 interrupted sutures on the anterolateral edge of the hiatus, then fix the gastric fundus to the lateral part of the diaphragm, covering the sutured area. Next, suture the anterior wall of the stomach along its longitudinal axis to the anterior abdominal wall to prevent sliding of the cardia and gastric rotation.

(4) Postoperative management: Special attention must be paid to preventing early postoperative vomiting. To achieve this, maintain the patency of the gastrointestinal decompression tube or gastrostomy tube, avoid morphine, and administer trifluoperazine 10mg every 6 hours for 24 hours. These patients often experience gastric atony postoperatively, requiring gastrointestinal decompression for one week. Once bowel sounds and flatus return, offer tea, broth, gelatin ice cream, water, and mild ginger ale, avoiding iced or carbonated drinks. Gradually transition to soft foods after one week.

5. Surgical Treatment of Peptic Esophageal Stricture Severe stenosis at the esophagogastric junction may result from primary reflux disease or localized acid production in the lower esophagus. In the latter case, the lower esophageal sphincter remains intact, as seen in Barrett's syndrome.

Treatment of peptic strictures includes preoperative or postoperative dilation of the strictured segment, followed by anti-reflux surgery. If reflux is due to delayed gastric emptying, consider gastrectomy, vagotomy, or pyloroplasty. In severe cases with significant esophageal shortening where restoring the abdominal segment is difficult, perform a supradiaphragmatic fundoplication or a Collis gastroplasty to extend the esophagus, enabling a subdiaphragmatic fundoplication. For severe peptic strictures that are difficult to dilate, heavily injured, or in cases with prior surgery (including Barrett's esophagus to prevent cancer), consider resection of the strictured segment and reconstruction with jejunum or colon. In cases of reflux esophagitis leading to stenosis due to hiatal hernia, dilation combined with posterior gastropoxy or fundoplication can resolve both the stenosis and esophagitis. Dilation alone only relieves dysphagia, but corrosive gastric reflux may recur, causing symptom relapse. Therefore, hernia repair and anti-reflux surgery must follow dilation.

(1) Collis Gastroplasty: This procedure is indicated for: - Peptic strictures of the lower esophagus with significant shortening, making fundoplication via an abdominal approach difficult; - High-risk surgical cases; - Surgeons lacking experience in esophageal replacement with colon or jejunum.

The patient was placed in the right lateral decubitus position, and a thoracoabdominal incision was made through the left 7th or 8th rib bed under general anesthesia. The esophagus was mobilized as much as possible up to the level of the aortic arch and encircled with an esophageal tape. If the stomach could be reduced into the abdominal cavity, a Belsey or Nissen hernia repair was performed to conclude the operation. If the stomach could not be returned to the abdominal cavity, a large gastric tube was first inserted through the esophagus into the stomach, and the tube was tilted toward the lesser curvature to serve as a marker. A gastrointestinal stapler was used to transect and suture between the esophagus and gastric fundus alongside the tube, creating a 5 cm long gastric tube to lengthen the esophagus. If necessary, the stapler could be used a second time to extend it by another 3 cm. The suture margins were inspected, and meticulous hemostasis was performed. Methylene blue solution could be injected through the gastric tube to ensure there was no fistula between the esophagus and gastric fundus. A fundoplication was performed by wrapping the gastric fundus around the newly formed distal esophagus, which was then returned to the abdominal cavity. The diaphragmatic crura and arcuate ligament were exposed, and the lesser curvature of the stomach was sutured to the arcuate ligament at the level of the newly formed His angle. The hiatus was narrowed anterior to the esophagus through the diaphragmatic crura, leaving it just wide enough to easily admit an index finger.

(2) Thal patch and Nissen fundoplication: In cases with rigid annular scar tissue in the peptic stricture segment, even after tension dilation followed by hernia repair, stricture recurrence may still occur. For these patients, the Thal patch technique can be employed. The strictured segment is longitudinally incised, and the gastric fundus is used as a graft to patch the defect created by the incision, with the serosal surface facing the esophageal lumen. Typically, within three weeks, the serosal surface will be covered by squamous epithelium. Alternatively, a free skin graft can be applied to the serosal surface to accelerate healing, reduce contracture, and prevent stricture recurrence. However, the Thal patch technique alone cannot prevent gastroesophageal reflux, necessitating a fundoplication procedure. Patients who undergo this combined surgical approach achieve long-term cure in approximately 85% of cases.