| disease | Thermal Burn |

"Burns" can be caused by factors such as hot water, steam, flames, electricity, lasers, radiation, acids, alkalis, phosphorus, etc. The commonly referred to or narrowly defined burns are those caused solely by high temperatures, known as thermal burns, which are frequently encountered in clinical settings. Burns caused by other factors are designated by their specific cause, such as electrical burns, chemical burns, etc.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

The pathological changes of thermal burns depend on the temperature of the heat source and the duration of exposure. Additionally, the occurrence and progression of burns are also related to the patient's physical condition. For example, some debilitated patients may accidentally suffer second-degree burns when using a hot water bag at 40-50°C, which is related to the tissue's ability to conduct heat. Another example is that the systemic response to burns in children is often more severe than in adults with burns of the same area (as a percentage of body surface) and concentration.

Pathological changes, in addition to direct local tissue cell damage caused by high temperature, are also due to various reactions of the body. After a burn, the body's response may release: ① stress hormones, due to pain stimulation, reduced blood volume, etc., leading to increased release of Black Catechu phenols, corticosteroids, antidiuretic hormone, vasopressin, aldosterone, etc.; ② inflammatory mediators, due to damage to tissue cells at the injury site or bacterial contamination, leading to the release of bradykinin, complement fragments (C3a, C5a, etc.), histamine, tryptamine, etc.; ③ arachidonic acid, due to the action of phospholipase, etc., transforming into prostaglandins (PG), thromboxanes (TX), and leukotrienes (LT); ④ various other factors, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF), interleukins (IL), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), etc. The above various bioactive substances can cause local inflammation and systemic responses to burns. The use of drugs such as corticosteroids and indomethacin can reduce the body's response, but they should only be used appropriately, otherwise they may increase complications.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsTo properly manage thermal burns, it is essential to first assess the extent and depth of the burn, closely monitor changes in the wound and overall condition, and be vigilant for the occurrence of complications.

I. Extent and Depth of Burns As mentioned, these two factors are closely related to the severity of the condition.

1. Estimation of Extent The extent is expressed as a percentage of the body surface area affected by the burn. Researchers have proposed several estimation methods. Currently, the Chinese Rule of Nines and the palm method are used domestically, with the latter being suitable for small-area burns.

The Rule of Nines divides the body into sections, each representing 9% of the total body surface area, primarily applicable to adults. For children, adjustments are needed due to their larger head and smaller lower limbs. Specific methods are detailed in Table 1 and can be illustrated in a diagram (Figure 1) attached to the medical record for reference.

Figure 1: Diagram of Percentage Distribution of Body Surface Areas in Adults

The palm method estimates that one palm (with fingers together) of the patient represents 1% of the body surface area.

2. Identification of Depth Burns are classified into 1st degree, superficial 2nd degree, deep 2nd degree, and 3rd degree based on the depth of tissue injury (Figure 2).

1st Degree Burns: Only the epidermis is affected. The area appears red and swollen, hence also called erythematous burns; there is pain and burning sensation, with slightly increased skin temperature. Recovery occurs within 3-5 days, with peeling but no scarring.

2nd Degree Burns: Extend into the dermis, with local blister formation, hence also called blister burns. (a) Superficial 2nd Degree Burns affect only the superficial layer of the dermis, with some of the germinal layer intact. Due to significant exudation, blisters are full and rupture easily, with noticeable exudate from the wound; the base of the wound is swollen and red; there is severe pain and hypersensitivity; skin temperature is elevated. Without complications like infection, healing occurs in about 2 weeks, with no scarring but possible temporary pigmentation, and good skin function. (b) Deep 2nd Degree Burns affect the deeper layers of the dermis, with some skin appendages remaining. Due to the thicker necrotic superficial tissue, blisters are smaller or flatter, sensation is slightly dulled, and skin temperature may be slightly lower. After removing the epidermis, the wound appears light red or red-white, with possible visible network of thrombosed vessels; surface exudate is minimal, but the base is significantly swollen. Without complications like infection, healing occurs in 3-4 weeks, with some granulation tissue during repair, leading to scarring but generally preserving skin function.

Figure 2: Diagram of Depth Classification of Thermal Burns

Table 1: Chinese Rule of Nines

| Body Part | Percentage of Adult Body Surface | Percentage of Child Body Surface | ||

| Head and Neck | Scalp | 3 | 9 | 9 + (12 - age) |

| Face | 3 | |||

| Neck | 3 | |||

| Upper Limbs | Upper Arms | 7 | 9×2 | 9×2 |

| Both forearms | 6 | |||

| Both hands | 5 | |||

| Trunk | Front of the trunk | 13 | 9×3 | 9×3 |

| Back of the trunk | 13 | |||

| Perineum | 1 | |||

| Both lower limbs | Both buttocks | 5* | 9×5+1 | 9×5+1-(12-age) |

| Both thighs | 21 | |||

| Both calves | 13 | |||

| Both feet | 7* | |||

Third-degree burns: The injury affects the entire thickness of the skin and may even extend to the subcutaneous tissue, muscles, and bones. Necrosis and dehydration of the skin can form eschar, hence also known as eschar burns. The wound surface has no blisters, appears waxy white or charred, and may show tree-like thrombosed blood vessels; it feels like leather to the touch; and may even be carbonized. Sensation is lost; skin temperature is low. Natural healing is very slow, requiring the eschar to fall off and granulation tissue to grow before forming scars, with only the edges having epithelium, not only losing skin function but often causing deformities. Some wounds may even be difficult to heal on their own.

First-degree burns are easy to identify. Superficial second-degree and deep second-degree, deep second-degree and third-degree burns are sometimes not easy to identify immediately after the injury. If the heat acting on the wound is uneven, there may be transitional areas between burns of different depths. The changes in the wound surface under the epidermis may not be immediately visible. Infection of the wound or complications such as deep shock can increase the depth of skin damage, making second-degree burns appear as deep second-degree, and deep second-degree as third-degree.

II. Severity classification of burns: To design treatment plans, especially when dealing with batches of casualties, organizing manpower and material conditions, it is necessary to classify the severity of burns. The following classification method is commonly used in our country:Grade I burns: Second-degree burns covering less than 9% of the body surface area.

Grade II burns: Second-degree burns covering 10-29% of the body surface area; or third-degree burns covering less than 10%.

Grade III burns: Total burn area of 30-49%; or third-degree burns covering 10-19%; or second-degree and third-degree burns not reaching the above percentages but with complications such as shock, respiratory burns, or severe combined injuries.

Severe burns: Total burn area of more than 50%; or third-degree burns covering more than 20%; or with severe complications.

In addition, clinically, burns are often referred to as small, medium, and large area burns to indicate the severity of the injury, but the distinction criteria are not yet clear. Therefore, medical records should still clearly state the area (%) and depth.

III. Local lesions: After heat acts on the skin and mucous membranes, cells at different levels undergo degeneration and necrosis due to protein denaturation and enzyme inactivation, and then fall off or form scabs. Strong heat can carbonize the skin and even its deep tissues.

The capillaries in the burn area and adjacent tissues may undergo changes such as congestion, exudation, and thrombosis. Exudation is the result of increased vascular permeability, and the exudate consists of plasma components (with slightly lower protein concentration), which can form blisters between the epidermis and dermis and edema in other tissues.

IV. Systemic Response: For small, superficial thermal burns, apart from pain stimulation, the impact on the whole body is not significant. However, larger and deeper thermal burns can cause the following systemic changes.

1. Reduced Blood Volume: Within 24 to 48 hours after injury, the permeability of capillaries increases, leading to the loss of plasma components into the interstitial space (third space), blisters, or outside the body (after blister rupture), thus reducing blood volume. In severe burns, besides the exudation at the injury site, other areas may also experience increased vascular permeability due to the action of inflammatory mediators, further reducing blood volume. In addition to exudation, the evaporation of water accelerates in the burn area due to the loss of skin function, exacerbating dehydration.

When blood volume decreases, the body regulates through the neuroendocrine system to reduce kidney urination to retain body fluids and produce a sense of thirst. Capillary exudation can decrease to a stop after the peak period, and interstitial exudate can gradually be absorbed. However, if the reduction in blood volume exceeds the body's compensatory capacity, shock can occur.

2. Energy Deficiency and Negative Nitrogen Balance: After injury, the body's energy consumption increases, catabolism accelerates, and negative nitrogen balance occurs.

3. Red Blood Cell Loss: Severe burns can reduce red blood cell counts, possibly due to intravascular coagulation, red blood cell sedimentation, changes in red blood cell morphology leading to easier destruction or phagocytosis by the reticuloendothelial system, thus leading to hemoglobinuria and anemia.

4. Reduced Immune Function: Post-injury hypoproteinemia, increased oxygen free radicals, and the release of certain factors (such as PGI2, IL-6, TNF, etc.) can all reduce immunity; coupled with the weakened chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and killing effects of neutrophils, burns are prone to complications of infection.

V. Systemic Reactions and Complications: The severity of grade II and above burns actually includes their systemic reactions and complications, and complications can even endanger patients with grade I burns. Preventing or mitigating complications can promote the smooth or improved healing of burn patients. Therefore, it is essential to pay attention to the early manifestations of systemic reactions and complications of burns.

Manifestations of hypovolemia mainly include thirst, dry lips, oliguria, increased pulse rate, low blood pressure, increased hematocrit, etc. If shock occurs, there may be dysphoria, restlessness or apathy, slow response, cold sweating or cold and wet extremities, weak or imperceptible pulse, significantly reduced or unmeasurable blood pressure, very little urine or only observable after catheterization, reduced central venous pressure, etc.

Burns are prone to complications of infection, and suppuration on the wound is easily detected. However, infections under necrotic tissue and eschar, as well as systemic infections, may be overlooked. In this seasonal disease, body temperature significantly rises, and white blood cells and their neutrophil percentage significantly increase; but in severe patients, body temperature may instead decrease, and white blood cells may not increase or decrease. Wound secretions and blood should be taken for bacterial culture and drug sensitivity tests.

It is also necessary to monitor the functions of important organs such as the kidneys and lungs according to the severity of the burn. For example, for changes in kidney function, in addition to calculating hourly urine output, routine urine tests (including specific gravity), blood/urine creatinine, blood/urine sodium, etc., should be performed. For lung changes, in addition to physical examination of the respiratory system, chest X-rays and blood gas analysis may be required. In summary, it is crucial to promptly detect and diagnose various complications of burns to take timely treatment measures.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

I. Treatment Principles

1. Protect the burned area, prevent and minimize external contamination.

2. Prevent and treat hypovolemia or shock.

3. Treat local and systemic infections.

4. Promote early healing of the wound using non-surgical and surgical methods, and minimize functional impairment and deformity caused by scarring.

5. Prevent and treat multi-system organ failure.

For grade I burns, the main treatment is wound care and prevention of local infection, and a small amount of sedatives and fluids can be used.

For burns above grade II, due to the greater systemic response and more common complications, both local and systemic treatments are required. Within 24 to 48 hours after the injury, the focus should be on preventing and treating hypovolemic shock. For the wound, in addition to preventing infection, efforts should be made to promote early healing, especially for third-degree burns. If these two requirements are met, burns above grade II can also be successfully treated.

II. On-site First Aid Proper on-site first aid lays a good foundation for subsequent treatment. Conversely, improper or hasty first aid can delay treatment and hinder healing.

1. Protect the injured area ① Quickly remove the heat source. If there is cold water nearby, rinse or immerse the area to lower the local temperature. ② Avoid further injury to the area. Clothing, pants, and socks on the injured area should be cut off and not peeled off. During transport, keep the injured area elevated to avoid pressure. ③ Reduce contamination by covering the wound with clean sheets, clothes, or simple bandages.

2. Sedation and pain relief ① Comfort and encourage the injured person to stabilize their emotions, avoid panic and dysphoria. ② Use sedatives like diazepam or pethidine (Dolantin) as appropriate. Since severe injuries may already have shock, medication should be administered intravenously, but care must be taken to avoid respiratory depression. ③ Severe pain from hand and foot burns can often be relieved by cold immersion.

3. Respiratory care After flame burns, the respiratory tract is damaged by smoke and heat. It is crucial to ensure airway patency, perform a timely tracheotomy (do not wait for obvious signs of respiratory distress), and provide oxygen. Unconscious burn patients also need to maintain airway patency.

Additionally, check for combined injuries, and perform corresponding first aid for major bleeding, open pneumothorax, fractures, etc.

III. Wound Management First-degree burns generally only require keeping the area clean and avoiding further injury. For larger areas, cold compresses or commercially available burn ointments can be used to relieve pain. For second-degree burns and above, the following treatment methods are needed.

(A) Initial stage [first stage] wound management Refers to the immediate treatment upon admission, also known as burn debridement, aiming to minimize wound contamination. However, those with concurrent shock must first undergo anti-shock treatment. Debridement can only be performed after the shock has improved.

Trim hair and overgrown nails. Clean the healthy skin around the wound. Rinse the wound with sterile saline or disinfectant (such as benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine, domiphen, etc.), gently remove surface debris, and clear the broken blister epidermis until the wound is clean. Debridement, except for small burns that can be performed in the treatment room, should generally be done in the operating room. To relieve pain, administer analgesics and sedatives first.

(B) Medication for fresh wounds Mainly to prevent infection and promote wound healing. Choose medication based on the severity and area of the burn.

1. For small second-degree burns with intact blisters, apply iodine or chlorhexidine to the surface; then aspirate the blister fluid and bandage.

2. For larger second-degree burns with intact blisters or small areas with broken blisters, remove the blister epidermis; then apply "Moist Burn Ointment" (a combination of Chinese and Western medicine) or other burn ointments (containing antibacterial agents and corticosteroids), or use other prepared Chinese and Western medicinal liquids (can be guided with single-layer paraffin oil gauze or medicinal liquid gauze adhering to the wound). The wound can be exposed or bandaged.

For third-degree burns, the surface can also be initially treated with iodophor in preparation for eschar removal.

Note: The wound should not be treated with Chinese Gentian violet, mercurochrome, or Chinese medicinal powders, as these can hinder wound observation. Antibiotics should also not be used indiscriminately, as they can easily lead to bacterial resistance.

(3) Wound Dressing or Exposure After cleaning and medicating the wound, it can either be dressed or left exposed. Dressing can protect the wound, prevent external contamination, absorb some of the exudate, and help the medication adhere to the wound. However, dressing makes it inconvenient to observe changes in the wound, hinders body surface heat dissipation, and does not prevent internal contamination. Over-tight dressing can affect local blood circulation. Exposing the wound allows for continuous observation of changes, facilitates the application of medication, and the management of scabs. However, it may be subject to external contamination or abrasion. Therefore, these two methods should be chosen based on specific circumstances.

1. Wounds on the limbs are mostly dressed, especially on the hands and feet, with fingers and toes dressed separately. Small wounds on the torso can also be dressed, first covering the wound with a layer of oil gauze or several layers of medicated gauze, then adding a 2-3 cm thick absorbent cotton pad or standard dressing, followed by bandaging from distal to proximal (exposing the extremities as much as possible), applying even pressure (but not too tight). After dressing, the tightness of the dressing, any soaking, odor, and extremity circulation should be regularly checked, and attention should be paid to signs of infection such as high fever, significant increase in white blood cells, and increased pain at the injury site. If the dressing becomes loose, it should be redressed; if too tight, it should be slightly loosened. Soaked dressings should be replaced with dry ones, and if there is no obvious infection, the inner layer does not need to be replaced. If infection has occurred, adequate drainage is necessary. For superficial second-degree burn wounds, if there are no adverse conditions, the dressing can be kept for 10-14 days before the first change. For deep second-degree or third-degree wounds, the dressing should be changed after 3-4 days to observe changes, or to manage scabs or eschars. Large-area dressing is not suitable in high-temperature environments.

2. Wounds on the head, face, neck, and perineum should be exposed. Large-area wounds should also be exposed. The bed sheets, treatment towels, and covers used must be sterilized, and the ward space should be kept as bacteria-free as possible, maintaining a certain temperature and humidity. During the exudation period, medication (bacteriostatic, astringent) can be applied to the wound, and excessive secretions should be regularly absorbed with cotton balls to reduce bacterial reproduction and avoid the formation of thick scabs. The wound should be kept as pressure-free as possible or pressure should be minimized, for which regular turning or the use of air mattresses is necessary. Before and after the formation of scabs or eschars, attention should be paid to whether there is deep infection or suppuration. In addition to observing changes in body temperature and white blood cells, a thick needle puncture or slight cutting of the scab may be necessary to observe the condition.

3. For multiple burns across the body, a combination of dressing and exposure methods can be used.

(4) Debridement The natural healing process of deep burn wounds is slow, or may not heal at all. During the period when the wound is not healed, not only does the patient suffer and their constitution deplete, but infection can also spread or other complications can occur. After natural healing, such wounds may form scars or hypertrophic scars (keloids), which can cause deformities and functional impairments. Therefore, active management is necessary to promote early wound healing. In principle, deep burns should be treated with exposure therapy, and surgical debridement and skin grafting should begin within 48-72 hours. The larger the area, the more active measures should be taken to remove the scab as early as possible and cover the wound with skin grafts.

1. Surgical Debridement and Tangential Excision Debridement is mainly used for third-degree burns, and the plane should reach the deep fascia (slightly shallower on the face and back of the hand). If deep tissues have become necrotic, they should be excised together. After thorough hemostasis of the wound, skin grafting should be performed as soon as possible. Tangential excision is mainly used for deep second-degree burns, removing necrotic tissue to create a fresh or essentially fresh wound surface, followed by skin grafting. For deep second-degree burns on the hands and joints, to restore function as soon as possible, debridement can also be used. Such surgeries involve more bleeding, and a tourniquet can be used on the limbs to reduce bleeding, with sufficient blood transfusion prepared before surgery. Both debridement and tangential excision require clear identification of the necrotic tissue layers, otherwise, the success of skin grafting may be affected.

2. Scab Removal: First, keep the surface of the scab dry to prevent infection under the scab as much as possible. When the tissue under the scab autolyzes and the scab separates from the base (about 2 weeks later), cut off the scab. The wound surface is granulation tissue and often has varying degrees of infection. Use methods such as wet compresses with medicinal solutions and soaking to control infection and promote good growth of granulation tissue. When the granulation tissue on the wound surface is free of purulent material, has a fresh color, no edema, and bleeds fresh blood upon touch, skin grafting can be performed. This method gradually removes the scab and is called the "silkworm erosion scab removal method." To reduce infection and accelerate scab separation, medications such as antibiotics, proteases, or Chinese medicinal preparations can be applied to the wound surface, but mature experience has not yet been achieved. The scab removal method is simpler than the excision and shaving methods, but it inevitably leads to infection and prolongs treatment time, so it should not be the preferred method for scab removal.

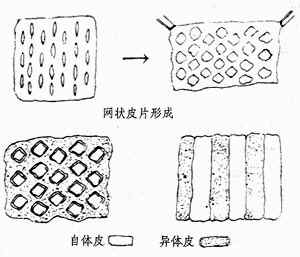

(5) Skin grafting The purpose is to promote early wound healing, thereby reducing burn complications and facilitating functional recovery. The autologous skin used is medium-thickness or thin-layer, made into large mesh, small stamp-like, or granular pieces; allogeneic skin is taken from fresh cadavers (excluding those who died from pestilence, infectious diseases, malignant tumors, etc.), used fresh or stored at deep low temperatures for future use; xenogeneic skin is mostly taken from piglets. After the autologous skin graft survives, the epithelial cells at its edges can grow. Allogeneic and xenogeneic skin grafts will eventually dissolve after surviving on the wound, so they are suitable when autologous skin is insufficient. The method of alternating autologous and allogeneic skin grafts (Figure 1) is used, where the autologous skin grows and extends to cover the wound during the dissolution of the allogeneic skin. Traditionally, autologous skin is often taken from the thigh and abdomen; now, for treating large-area burns, the scalp is chosen because its dermis is thicker and has good blood circulation, allowing repeated thin skin harvesting without affecting its function.

The skin source required for skin grafting of large-area burn wounds is often insufficient. Therefore, scholars at home and abroad are dedicated to the development of artificial skin. Raw materials include silicone, collagen, etc., such as China's artificial skin types 41, T41, Nanjing II, etc., which protect the wound after eschar removal. Another new technology is to take autologous skin for cultivation, expand it, and use it to replace the initially transplanted allogeneic skin.

Figure 1 Several types of skin grafts for burns

(6) Treatment of infected wounds Infection not only erodes tissue and hinders wound healing but can also lead to sepsis and other complications. It must be carefully managed to eliminate pathogens and promote tissue regeneration.

For purulent secretions on the wound, methods such as wet compresses, semi-exposure (thin layer of medicated gauze coverage), or immersion are selected to remove them, preventing the formation of pus scabs. It is necessary to promote the growth of fresh granulation tissue (which has a certain defensive role) on the infected wound to facilitate skin grafting or self-healing.

Wound medication: ① For general suppurative bacteria infections (Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus albus, Escherichia coli, etc.), nitrofurazone, benzalkonium bromide, chlorhexidine, eusol, etc., or Coptis Rhizome, Giant Knotweed, purpleflower holly leaf, Rhubarb Rhizoma, etc., can be used to make medicated gauze for wet compresses or washes. ② For Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, where the wound has green pus, erosion of granulation tissue and wound edge epithelium, and increased necrotic tissue, bacteriological examination should be performed. Acetic acid, phenoxyethanol, sulfamylon, silver sulfadiazine, etc., can be used for wet compresses or cream application. ③ Fungal infections (Candida albicans,  Aspergillus, Mucor, etc.) occur in critically ill patients using broad-spectrum antibiotics, adrenal corticosteroids, etc. The wound appears darker, with mold spots or granules, pale granulation tissue edema, and mold spots may also appear on the dressing. Fungal examination can confirm the diagnosis. Garlic solution, iodine glycerin, nystatin, clotrimazole, etc., are selected for the wound; at the same time, broad-spectrum antibiotics and hormones must be discontinued.

Aspergillus, Mucor, etc.) occur in critically ill patients using broad-spectrum antibiotics, adrenal corticosteroids, etc. The wound appears darker, with mold spots or granules, pale granulation tissue edema, and mold spots may also appear on the dressing. Fungal examination can confirm the diagnosis. Garlic solution, iodine glycerin, nystatin, clotrimazole, etc., are selected for the wound; at the same time, broad-spectrum antibiotics and hormones must be discontinued.

After the infection of larger wounds is basically controlled and granulation tissue grows well, skin grafting should be promptly performed to promote wound healing.

IV. Systemic treatment Grade II and above burns cause significant systemic reactions, and shock can occur early. Therefore, systemic treatment must be emphasized after the injury, and those with critical conditions such as shock should be treated before managing the wound.

(1) Prevention and treatment of hypovolemic shock The main method is to maintain effective blood circulation volume by fluid replacement based on the area of II° and III° burns.

1. Volume and types of early fluid replacement Researchers both domestically and internationally have designed various protocols (formulas) for burn fluid therapy. Table 2 lists the commonly used protocols in China. According to this protocol, a patient weighing 60 kg with a 30% second-degree burn should receive a fluid replacement volume of [60×30×1.5 (additional loss)] + 2000 (basic water requirement) = 4700 (ml) within the first 24 hours, including 1800 ml of crystalloid solution, 900 ml of colloid solution, and 2000 ml of glucose solution. In the second 24 hours, the patient should receive 900 ml of crystalloid solution, 450 ml of colloid solution, and 2000 ml of glucose solution (total 3350 ml). The preferred crystalloid solution is balanced salt solution, as it can avoid hyperchloremia and correct partial acidosis; isotonic saline is the second choice. The preferred colloid solution is plasma, to replenish the lost plasma proteins; however, plasma is not easily available, so dextran or hydroxyethyl starch can be temporarily used as substitutes; whole blood is not suitable due to the presence of red blood cells during hemoconcentration after burns, but it is applicable when a large number of red blood cells are damaged in severe burns.

Table 2: Fluid Replacement for II° and III° Burns

| Within the first 24 hours | Within the second 24 hours | ||||||

| Fluid replacement per 1% body surface area and per kg body weight (for additional loss) | Adults | Children | Infants | Half of the first 24 hours | |||

| 1.5ml | 1.8ml | 2.0ml | |||||

| Crystalloid: Colloid | Moderate, grade III | 2:1 | Same as above | ||||

| Severe | 1:1 | ||||||

| Basic water requirement (5% glucose) | 2000ml | 60~80 | 100 | Same as above | |||

| ml/kg | ml/kg | ||||||

2. Fluid Replacement Method: Due to the rapid reduction in blood volume caused by fluid loss within 8 hours after a burn, half of the fluid replacement for the first 24 hours should be administered within the first 8 hours, and the remaining half should be administered over the next 16 hours. In terms of expanding blood volume, intravenous fluid replacement is more effective than oral fluid replacement. Especially for patients with larger burn areas or (and) reduced blood pressure, rapid intravenous infusion is necessary. Effective peripheral or central venous access (puncture, catheterization, or incision) is recommended. For patients with pre-existing heart or lung diseases, care must be taken to avoid heart failure or pulmonary edema caused by too rapid infusion. Initially, crystalloid solutions are preferred to improve microcirculation; after a certain amount (not the entire estimated amount) of crystalloid solution is administered, a certain amount of colloid solution and 5% glucose should be given; then repeat this sequence. 5% glucose should not be administered excessively or continuously in the entire estimated amount, otherwise it will significantly worsen edema. For III° burns covering more than 10% of the body surface area or patients with deep shock, sodium bicarbonate should be added to correct acidosis and alkalinize the urine. Oral drinks (containing 0.3g of sodium chloride, 0.15g of sodium bicarbonate per dl, or with a small amount of sugar, flavoring, etc.) can have a fluid replacement effect, but care must be taken to avoid causing acute gastric dilation.

The above is the fluid replacement method within 48 hours after injury. Starting from the 3rd day, intravenous fluid replacement can be reduced or only oral rehydration can be used to maintain fluid balance.

Due to the differences in the condition of burn patients and their physical conditions, the effects of fluid replacement vary. Therefore, it is necessary to closely observe the specific situation in order to adjust the fluid replacement method appropriately. The manifestations of insufficient blood volume include: ① thirst. ② Urine output less than 30ml per hour (adults), with high specific gravity. ③ Increased pulse rate and low blood pressure (or decreased pulse pressure). ④ Difficulty in filling superficial veins in the limbs and subungual capillaries. ⑤ Dysphoria and restlessness. ⑥ Low central venous pressure. For severe burn patients, especially those complicated with shock, it is necessary to place a urinary catheter and a central venous catheter for monitoring. In addition, it is also necessary to test hemoglobin and hematocrit, blood pH, and CO2 combining power. When there are signs of insufficient blood volume, the infusion should be faster, and when the condition improves, the infusion should be slowed down until oral intake can be maintained. Sometimes rapid infusion can cause a temporary increase in blood volume (high central venous pressure), and diuretics should be used to reduce the cardiac load.

(2) Prevention and treatment of systemic infection. Systemic infection after burns, a few may occur in the early stage combined with shock (called fulminant sepsis), the consequences are extremely serious; the rest are more likely to occur during the tissue edema fluid recovery stage (mostly 48-72 hours after injury); when eschar separation or extensive escharectomy occurs, it is also prone to occur. In fact, bacteria may invade the bloodstream when the wound is not healed. Especially when the body's resistance is reduced, such as large areas of deep burns, reduced white blood cells and immune function, sepsis is prone to occur. The manifestations include: ① Body temperature above 39℃ or below 36.5℃. ② Wound collapse, dark and dull granulation, increased necrotic tissue, sudden retraction of inflammatory reaction at the wound edge, autolysis of new epithelium, etc. ③ Appearance of petechiae on the wound or healthy skin. ④ White blood cell count too high or too low. ⑤ Dysphoria, restlessness, apathy, drowsiness, and other mental abnormalities. ⑥ Signs of shock. ⑦ Respiratory distress, abdominal distension and fullness, etc.

1. Prevention and treatment of infection must start with careful wound management. Otherwise, relying solely on antibiotic injections is difficult to be effective.

2. Selection of antibiotics. ① In the early stage after injury, it is advisable to use a large dose of penicillin G injection, which can be combined with clavulanic acid or sulbactam (β-lactamase inhibitors), and is effective against Staphylococcus aureus and common mixed infections. ② When there is obvious infection on the wound, it is often a mixed infection of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and ampicillin, metronidazole, erythromycin, lincomycin, cefoxitin, cefazolin, etc. can be selected. ③ When there is Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, carbenicillin, sulbenicillin, cefsulodin, polymyxin B, etc. can be selected. When selecting antibiotics for injection, pay attention to the patient's liver and kidney function status to prevent more side effects from large doses of medication.

Clearing heat and removing toxin Chinese medicinals mostly have antibacterial effects, and such injection preparations as purpleflower holly leaf, barberry root, "heat toxin clear", etc. can also be selected.

3. Immune enhancement therapy. ① Timely injection of tetanus antitoxin serum after injury. ② For Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, immunoglobulin or immune plasma, combined with Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine or combined vaccine (containing Staphylococcus aureus) can be used. ③ Fresh plasma can enhance general immune function. Other immunomodulators manufactured by bioengineering technology are under research and trial.

(3) Nutritional therapy. After burns, the mechanism of consumption increases, consistent with the extent of the affected area, concentration, infection, etc. Insufficient nutrition can delay wound healing, reduce immunity, muscle weakness, etc., so supplementation is needed and has received widespread attention. Nutritional support can be provided through the gastrointestinal tract and intravenous routes, with gastrointestinal nutrition being preferred as it is closer to physiology and has fewer complications.

Due to a significant increase in resting energy expenditure, the total energy required for supplementation can reach 10500~1680 kJ (2500~4000 kcal), which should be provided by carbohydrates, proteins, and fats at 50%, 20%, and 30% respectively. Among these, carbohydrates and fats should be gradually increased, starting slightly below the required amount to prevent the formation of hyperglycemia (leading to unconsciousness) and excessive blood fatty acids. The amino acid mixture should be supplemented with arginine, glutamine, and branched-chain amino acids. Nutritional support should continue for a period after the wound has healed.

V. Nursing Care is an indispensable component of burn treatment. Meticulous nursing can facilitate smoother healing of burns, reduce complications and sequelae, and is particularly important for patients with second-degree burns or below. Psychological therapy should be emphasized from the moment the patient is admitted to alleviate their doubts and fears, and to build confidence and cooperation in treatment. It is essential to maintain the cleanliness of the hospital bed, utensils, and ward. Strict implementation of disinfection and sterilization procedures and routine management of burn wards should be enforced. A nursing plan should be formulated based on the specific condition, with a focus on key areas. For example, for facial burns, attention should be paid to eye care, upper respiratory tract care, oral hygiene, and diet; for burns on the limbs and hands, splints and bandages should be used to maintain appropriate positioning angles to facilitate late-stage [third stage] functional recovery. Monitor the patient's weight changes closely; for those experiencing rapid weight loss, implement gastrointestinal elemental nutrition or intravenous high (total) nutrition. Closely observe changes in the wound and overall condition (such as temperature, vital signs, fluid intake and output, etc.), and record in detail as a basis for adjusting treatment.

VI. Prevention and Treatment of Organ Complications The basic methods to prevent organ complications after burns are timely correction of hypovolemia, rapid reversal of shock, and prevention or reduction of infection. At the same time, it is necessary to focus on maintaining the function of certain organs according to the specific condition. For example, if oliguria, hemoglobinuria, or urinary casts appear, consider factors such as insufficient blood volume, hemolysis, or other renal damage factors, and take measures such as increasing perfusion, diuresis, alkalinizing urine, and discontinuing nephrotoxic antibiotics (such as gentamicin, polymyxin). If pulmonary infection or atelectasis occurs, actively perform sputum suction and dispelling phlegm, select antibacterial drugs, and strive to improve ventilation function and provide oxygen.

1. Shock Early stages are often characterized by hypovolemic shock. Subsequently, when complicated by infection, septic shock can occur. In cases of extremely severe burns, intense injury stimulation can immediately lead to shock.

2. Sepsis Burns compromise the skin's barrier function against bacteria; more severely affected patients also experience weakened leukocyte and immune functions, making them prone to infections. Pathogens may include resident skin flora (such as Staphylococcus aureus) or externally introduced bacteria (such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Purulent infections can occur on the wound surface and under the eschar. Infections may also progress to septicemia and septic shock. Additionally, following the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, especially in patients with systemic weakness, fungal infections may develop.

3. Pulmonary Infections and Acute Respiratory Failure Pulmonary infections can result from various causes, such as respiratory tract mucosal burns, pulmonary edema, atelectasis, sepsis, etc. They may also lead to adult respiratory distress syndrome or pulmonary infarction, resulting in acute respiratory failure.

4. Acute Renal Failure Preceding or following shock, renal ischemia can occur, leading to degeneration of the renal capsule and tubules in severe cases. Additionally, hemoglobin, myoglobin, and infectious toxins can damage the kidneys, potentially causing acute renal failure.

5. Stress Ulcers and Gastric Dilation Post-burn, duodenal mucosal erosion, ulcers, and bleeding, known as Curling ulcers, may occur, possibly related to gastrointestinal ischemia and subsequent hydrogen ion backflow damaging the mucosa after reperfusion. Gastric dilation is often caused by early weakened gastric motility and excessive water intake due to thirst in seasonal disease patients.

6. Other Complications Myocardial function may decrease, with reduced stroke volume, related to the production of myocardial depressant factors, infectious toxins, or myocardial hypoxia post-burn. Cerebral edema or liver necrosis may also be associated with hypoxia and infectious toxins. It is noteworthy that mortality in burn patients is often due to multiple system organ failure.