| title | Chinese Angelica |

| release time | 2006/4/22 |

| source | Jade Knock Studio |

Chinese Angelica is the dried root of the umbelliferous plant Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, cultivated in various regions, mainly in Min County, Wudu, Zhang County, Cheng County, Liangdang, Zhouqu, Xihe, Weiyuan, Wen County, and Gangu in Gansu Province. Among these, the output from Min County is the largest and of the highest quality, commonly known as "Min Gui." Additionally, it is also produced in Yunnan, Shaanxi, Sichuan, and Hubei.

Materia medica research suggests that the medicinal use of Chinese Angelica has always been dominated by Angelica sinensis of the Umbelliferae family. It was widely cultivated in Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Gansu during the Song and Ming dynasties, with the products from Shaanxi and Gansu being the most authentic. As for the historically mentioned "Liyang Chinese Angelica," "Du Chinese Angelica," and "Tu Chinese Angelica," these were substitutes used during special periods or in specific regions and were not mainstream in medicinal use.

bubble_chart Varietal Identification

The use of Chinese Angelica in medicine was first recorded in the Bencao Jing, listed as a middle-grade herb. The ancient name for Chinese Angelica was "薜," as mentioned in the "Er Ya": "薜, Shan Qi," with Guo Pu annotating: "Guang Ya says: Shan Qi, Chinese Angelica. Chinese Angelica today resembles Qi but is larger and coarser." As for the origin of the name Chinese Angelica, Chen Cheng's Bencao Bieshu explains: "For those with chaotic qi and blood, taking it will stabilize them, allowing qi and blood to return to their respective places. Thus, it can be used for emergencies postpartum and for quickly tonifying deficiency. It is feared that the sage who established the name Chinese Angelica must have derived it from this." This explanation may not be accurate, as Chinese Angelica in ancient times was likely similar to herbs like Mi Wu and Bi Zhi, used by poets to evoke longing and nostalgia, symbolizing the desire to return. For example, Cui Bao's "Gu Jin Zhu" states: "They presented each other with Wen Wu, also known as Chinese Angelica." The use of Chinese Angelica as a metaphor for Guilai (ST29) is frequently seen in literature. The "Records of the Three Kingdoms: Wu Zhi: Biography of Taishi Ci" mentions: "Cao Cao, hearing of his fame, sent Ci a letter sealed in a box. Upon opening it, there was nothing written, only stored Chinese Angelica." The "Book of Jin: Five Elements Zhi" records: "During the Taihe era of Emperor Ming of Wei, Jiang Wei returned to Shu, losing his mother. The Wei people had his mother write a letter calling for Wei to return, also sending Chinese Angelica as a metaphor. Wei replied: A hundred acres of good land, not counting one mu, only seeing Milkwort Root, no Chinese Angelica." Additionally, the "Biographies of Divine Monks" Volume 7, entry for Yixing, states: "(Emperor Xuanzong) once asked how long the nation's fortune would last and if there would be any difficulties. Yixing said: The imperial carriage will travel ten thousand miles, and the state will ultimately be auspicious. The emperor, startled, asked the reason, but he did not answer, instead presenting a small golden box, saying: Open it at ten thousand miles. One day, the emperor opened the box to find a small amount of Chinese Angelica. When the An Lushan rebellion forced the emperor to flee to Chengdu, upon reaching the Ten Thousand Mile Bridge, he suddenly understood, and not long after, he indeed returned." In these stories, "Chinese Angelica" is used to symbolize the idea of return.

Since the name Chinese Angelica carries metaphorical meanings, various regions have similar fragrant herbs referred to as "Chinese Angelica." The Bencao Jing Jizhu already revealed the confusion in varieties at that time: "Today, the Chinese Angelica from Longxi Daoyang Heishui is fleshy with few branches, fragrant, called Mawei Chinese Angelica, somewhat rare. The Chinese Angelica from northern Xichuan has many roots and branches and is thin. The product from Liyang is white with a weak scent, called Cao Chinese Angelica, used when in short supply. Some practitioners say true Chinese Angelica refers to this, due to its varying quality." Here, at least three types of Chinese Angelica are mentioned: Mawei Chinese Angelica from Heishui, Chinese Angelica from northern Xichuan, and Cao Chinese Angelica from Liyang. Among these, the "Liyang Chinese Angelica" from Anhui, despite being called "Cao Chinese Angelica" and "true Chinese Angelica" at the time, was viewed with skepticism by Tao Hong-jing regarding its intrinsic quality. The preface to the Bencao Jing Jizhu specifically states: "Since the Jiangdong era, many minor herbs have come from nearby regions, their potency and nature deficient compared to native products. If Jing and Yi were inaccessible, then entirely using Liyang Chinese Angelica and Qiantang Sanjian, how could they be similar? Thus, the deficiency in treating illnesses compared to the past must also be due to this reason."Xinxiu Bencao also has a similar statement, with a slightly more detailed description: "There are two types of Chinese Angelica seedlings, one resembling the large-leaf Sichuan Lovage Rhizome, and the other resembling the small-leaf Sichuan Lovage Rhizome, but the stems and leaves are lower than those of Sichuan Lovage Rhizome. They are now produced in Dangzhou, Dangzhou, Yizhou, and Songzhou, with the best coming from Dangzhou. The small-leaf variety is called Silkworm Head Chinese Angelica, and the large-leaf variety is called Horse Tail Chinese Angelica. The Silkworm Head variety is inferior and is no longer used. Tao Hong-jing mentioned that the Liyang variety is the Silkworm Head Chinese Angelica." The leaves of plants in the Apiaceae family are often similar in shape, making it difficult to infer the species based on simple descriptions. The Chinese Angelica referred to by Tao Hong-jing and Su Jing may include plants from the Apiaceae family, such as the Angelica genus, Ligusticum genus, and even other genera containing essential oils.

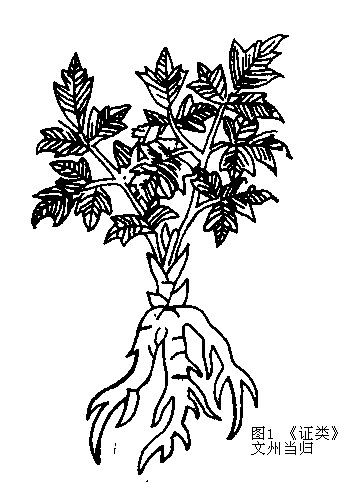

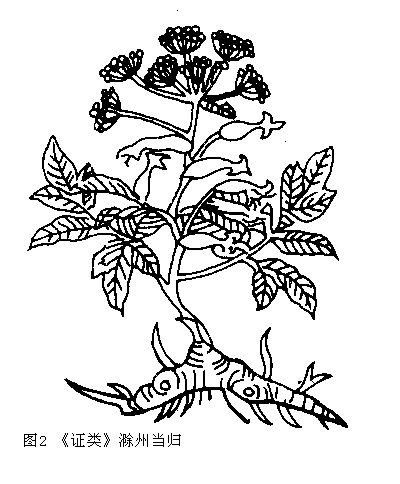

By the Song Dynasty at the latest, Chinese Angelica was already being cultivated in Sichuan. The "Bencao Yanyi" states: "The new 'Tújīng' suggests that Chinese Angelica is a type of celery, with the flatland variety called celery and the larger mountain variety called Chinese Angelica. If so, today in Sichuan, it is all cultivated in flatland fields, especially plump and rich in flesh, without distinguishing between flatland and mountain varieties, but the best are those that are plump and moist, not dry. Today, medical practitioners prefer this variety." During the Ming Dynasty, Chinese Angelica cultivation was more widespread in Sichuan and Shaanxi. The "Bencao Gangmu" mentions: "Today, people in Shaanxi, Sichuan, Qínzhōu, and Wènzhōu cultivate it for trade. The Qín variety, with round heads, many tails, purple color, fragrant aroma, and plump texture, is called 'Horsetail Guī,' and is superior to other varieties. Those with large heads, thick tails, white color, and hard, dry texture are called 'Glutton Head Guī,' suitable only for dispersing medicinal use." The highest-quality "Horsetail Guī" mentioned here aligns with the current variety in use.

Volume 13 of the "Bencao Gangmu" also mentions local Chinese Angelica, with no content under the collection and explanation section, but under the Pubescent Angelica entry, Li Shizhen notes: "Recently, a type of local Chinese Angelica has appeared in the rivers and lakes, about a foot long, with white flesh and black skin, and a fragrant aroma similar to Dahurian Angelica. People also call it water Dahurian Angelica, used as a substitute for Pubescent Angelica." Combining this with the illustrated medicinal drawing of local Chinese Angelica, its original plant is likely the Araliaceae local Chinese Angelica, also known as nine-eyed Pubescent Angelica, Aralia cordata Thunb. Additionally, the local Chinese Angelica mentioned in books like "Zhíwù Míngshí Túkǎo" and "Bencao Gangmu Shiyi" is more complex. Mr. Chen Chongming and Mr. Huang Shengbai's "Material Medica" has a dedicated discussion on this topic, which can be referenced.

bubble_chart Historical Evolution of Authentic Production Areas

Gansu has been the authentic production area of Chinese Angelica since ancient times. The Bencao Jing states: "Chinese Angelica grows in the valleys of Longxi." The Fanzi Jiran also mentions: "Chinese Angelica comes from Longxi, and the non-dried ones are good." The Liexian Zhuan, Volume II, also mentions that a person named Shan Tu from Longxi "consumed Rehmannia, Chinese Angelica, Notopterygium, Pubescent Angelica, and Sophora powder." The Longxi mentioned in the literature generally refers to the area around present-day Dingxi City, Gansu. The Wu Pu Materia Medica mentions that Chinese Angelica "may grow in the Qiang and Hu regions." The Liang Shu: Zhuyi Zhuan states: "In the fourth year of Tianjian, King Liang Mibo of Dangchang came to offer Liquorice Root and Chinese Angelica." Dangchang is now Min County, under the jurisdiction of Dingxi City, Gansu, which remains an authentic production area for Chinese Angelica to this day.

During the Tang Dynasty, the production of Chinese Angelica was concentrated in Gansu and Sichuan, with Jiannan Dao producing the most. According to records from "Xinxiu Bencao," "Qianjin Yifang," "Tongdian," "Tang Liu Dian," "Yuanhe Junxian Tuzhi," and "New Book of Tang," nine prefectures under Jiannan Dao—Maozhou, Yizhou, Weizhou, Songzhou, Dangzhou, Xizhou, Jingzhou, Zhezhou, and Gongzhou—all contributed Chinese Angelica as local tribute. Jiannan Dao, centered around Chengdu, covered most of present-day Sichuan Province, as well as parts of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Wen County in Gansu. This extensive production of Chinese Angelica might be related to Kou Zongshi's claim that Chinese Angelica was successfully cultivated in plain areas. It also foreshadowed the Song Dynasty's assertion that "Chinese Angelica from Sichuan is superior" (as stated by Su Song). However, at least during the Tang Dynasty, Dangzhou (now Tanchang County in Gansu), which belonged to Longyou Dao, remained the authentic production area for Chinese Angelica, as noted in "Xinxiu Bencao": "Dangzhou is the best."

In addition to specifically illustrating the medicinal diagram of Chinese Angelica from Wenzhou, "Bencao Tujing" also mentions: "Nowadays, it is found in various prefectures of Sichuan, Shaanxi, as well as in Jiangning Prefecture and Chuzhou, but the best comes from Sichuan." The ancient name of Heishui County in Aba Prefecture, Sichuan Province, was "Dangzhou," named after its production of Chinese Angelica, as recorded in "Taiping Huanyu Ji" (Volume 81) and "Yudi Guangji." "Shuzhong Guangji" (Volume 64) states: "Chinese Angelica is cultivated in Sichuan's fields, rich and oily, with no distinction between flatlands and mountains." Large-scale artificial cultivation was likely the reason Sichuan's Chinese Angelica became mainstream during the Song Dynasty.

In the section on the authenticity of Chinese Angelica, "Pin Hui Jingyao" ambiguously summarizes previous scholars' views without adding new insights. "Bencao Mengquan" states: "It grows in both Qin and Shu regions," and adds, "Chinese Angelica from Sichuan is strong in potency, while that from Qin is gentle and suitable for tonics," indicating that Chinese Angelica from Sichuan and Gansu each has distinct characteristics. "Bencao Gangmu" identifies the best Qin Chinese Angelica as "Mawei Gui," claiming it "surpasses all others."

According to "Yaowu Chanchu Bian": "The best Chinese Angelica comes from Hanzhong Prefecture in Shaanxi, Xing'an County, and Xigu." However, this claim is likely inaccurate. Based on the 1940 "Medicine Trade Regulations" by the Xi'an Traditional Medicine Trade Association, the production areas for Chinese Angelica, Chinese Angelica slices, and Chinese Angelica roots are all recorded as "Sichuan and Gansu," with no mention of Shaanxi. Therefore, throughout history, the finest Chinese Angelica has consistently come from the regions along the Min Mountains in Gansu and Sichuan, particularly from Min County and Wen County in Gansu.

bubble_chart Other Related Items