| disease | Hemorrhoids |

| alias | Haemorrhoids, Piles, Hemorrhoids |

Hemorrhoids are one of the most common diseases affecting human health, and their true incidence rate is unknown. In the past, there was a saying, "nine out of ten people have hemorrhoids," or even "nine out of ten men and ten out of ten women have hemorrhoids," which refers to the high prevalence of hemorrhoids. In 1977, a nationwide survey of 57,927 people across 155 units found that 33,837 people suffered from anorectal diseases, with a total incidence rate of 58.4%. Among them, the incidence of hemorrhoids accounted for 87.25%, with internal hemorrhoids being the most common at 59.86%, external hemorrhoids at 16.01%, and mixed hemorrhoids at 24.13%. These statistics sufficiently demonstrate that hemorrhoids are a common and frequently occurring disease.

Internationally, hemorrhoids are referred to as "Haemorrhoids" or "Piles," but the meanings of these two terms are entirely different. "Haemorrhoid" is derived from the Greek word "Haemorrhoids," meaning bleeding ("haem" for blood and "rhoos" for outflow). This name is based on the clinical feature of bleeding, but not all hemorrhoids bleed—some may never bleed. Later, the term "Piles" was derived from the Latin word "Pila," meaning "ball," which refers to the shape of hemorrhoids. This term encompasses all types of internal and external hemorrhoids. Currently, British scholars refer to hemorrhoids as "Piles."

Most scholars now believe that hemorrhoids are "vascular anal cushions," a normal part of anatomy present in all ages, genders, and ethnicities, and should not be considered a disease. Only when accompanied by symptoms such as bleeding, prolapse, or pain can they be classified as a disease. Based on the location of occurrence, internal hemorrhoids are divided into primary internal hemorrhoids (mother hemorrhoids) and secondary internal hemorrhoids (daughter hemorrhoids). This is related to vascular branching, as the main terminal branches of the superior rectal artery are distributed in the right anterior, right posterior, and left midline rectal columns.

bubble_chart Etiology

The exact cause of hemorrhoids is not fully understood, but it is believed to result from multiple factors. The following theories are currently proposed:

(1) Anal Cushion Prolapse TheoryThe anal vascular cushion, referred to as the "anal cushion," is a tissue pad located in the anal canal and rectum, existing as an anatomical structure from birth. Symptoms of hemorrhoids arise when the anal cushion becomes loose, hypertrophied, bleeds, or prolapses. The anal cushion consists of three components: ① veins, or venous sinuses; ② connective tissue; and ③ the Treitz muscle, a smooth muscle situated between the anal cushion and the internal anal sphincter, which helps anchor the cushion. When the Treitz muscle thickens or ruptures, the anal cushion prolapses. Goligher suggested that preserving the Treitz muscle during hemorrhoidectomy can prevent sphincter injury, reduce surgical trauma, and promote wound healing. He reported 100 cases, with 80% achieving initial-stage healing, minimal postoperative pain, and painless bowel movements for most patients. Normally, the anal cushion loosely attaches to the muscular wall and retracts into the anal canal after defecation due to its own fibrous contraction. However, when the anal cushion becomes congested or hypertrophied, it is prone to injury, bleeding, and prolapse outside the anal canal. The degree of congestion is influenced not only by anal canal pressure (e.g., constipation, pregnancy) but also by hormonal, genetic, and emotional factors.

(2) Varicose Vein Theory

Anatomically, the portal vein system and its branches, including the rectal veins, lack venous valves, making blood prone to stasis and venous dilation. Additionally, the superior and inferior rectal venous plexuses have thin walls, superficial locations, and low resistance, while the submucosal tissue at the distal rectum is loose—all of which facilitate venous dilation. Factors obstructing venous return, such as chronic constipation, pregnancy, prostatic hypertrophy, or large pelvic tumors, can further impede rectal venous drainage, leading to the formation of tortuous hemorrhoids. Infections of the anal glands or perianal region may also cause perivenous inflammation, resulting in venous dilation and hemorrhoid formation.

(3) Genetic, Geographic, and Dietary Factors

While no definitive evidence links genetics to hemorrhoid development, a family history is common among patients, possibly due to shared dietary habits, bowel habits, or environmental factors. Many believe that hemorrhoids are less prevalent in developing countries, such as rural Africa, where high-fiber diets are common. In developed nations, increased consumption of high-fiber foods not only helps prevent colorectal cancer but may also reduce the incidence of hemorrhoids.

Hemorrhoids are classified into three categories based on their location:

(1) Internal hemorrhoid

The surface is covered by mucous membrane, located above the dentate line, and formed by the internal hemorrhoidal venous plexus. It is commonly found in three areas: the left middle, right anterior, and right posterior regions. There is often a history of hematochezia and prolapse.

(2) External hemorrhoids

The surface is covered by skin, located below the dentate line, and formed by the external hemorrhoidal venous plexus. Common types include thrombosed external hemorrhoids, connective tissue external hemorrhoids (skin tags), varicose external hemorrhoids, and inflammatory external hemorrhoids.

(3) Mixed hemorrhoids

Located near the dentate line, covered by the junctional tissue of skin and mucous membrane, and formed by the anastomosing veins between the internal and external hemorrhoidal venous plexuses. They exhibit characteristics of both internal hemorrhoids and external hemorrhoids.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

(1) Hematochezia

The characteristics are painless, intermittent, and bright red blood after defecation, which are also common symptoms of internal hemorrhoids or mixed hemorrhoids in the early stages. Hematochezia is mostly caused by feces rubbing and damaging the mucous membrane or excessive straining during defecation, leading to the rupture and bleeding of dilated blood vessels. In mild cases, blood may appear on the stool or toilet paper, followed by dripping blood. In severe cases, bleeding may be喷射状, and hematochezia often stops spontaneously after a few days. This is of great significance for diagnosis. Constipation, dry and hard stools, alcohol consumption, and eating刺激性 foods are all诱因 for bleeding. If long-term反复 bleeding occurs, anemia may develop, which is not uncommon clinically and should be differentiated from bleeding disorders.

(2) Prolapse of hemorrhoids

This is often a symptom of the advanced stage. Prolapse usually occurs after hematochezia, as the enlarged hemorrhoids in the advanced stage gradually separate from the muscle layer and are pushed out of the anus during defecation. In mild cases, prolapse occurs only during defecation and retracts spontaneously afterward. In severe cases, manual reduction is required. In even more severe cases, slight abdominal pressure, such as coughing or walking, can cause the hemorrhoids to prolapse, making reduction difficult and rendering the patient unable to work. A small number of patients report prolapse as the initial symptom.

Simple internal hemorrhoids are painless, though a少数 patients may experience a sense of fullness. When internal hemorrhoids or mixed hemorrhoids prolapse and become incarcerated, leading to edema, infection, or necrosis, varying degrees of pain may occur.

(4) Cutaneous pruritus

In advanced-stage internal hemorrhoids, prolapsed hemorrhoids, and松弛 of the anal sphincter, secretions often leak out. Due to the irritation of these secretions, perianal cutaneous pruritus and discomfort may occur, and even skin eczema may develop, causing extreme discomfort for the patient.

The diagnosis of internal hemorrhoids primarily relies on anorectal examination. First, perform an anal inspection by gently pulling the anal opening apart with both hands. Except for first-stage internal hemorrhoids, the other three stages can usually be observed during this inspection. For cases involving prolapse, it is best to examine immediately after squatting for defecation, as this provides a clear view of the size, number, and location of the hemorrhoidal masses, which is particularly useful for diagnosing circumferential hemorrhoids. Next, perform a digital rectal examination: internal hemorrhoids without thrombosis or fibrosis are difficult to palpate, but the main purpose of this examination is to assess whether there are other abnormalities in the rectum, especially to rule out rectal cancer and polyps. Finally, conduct an anoscopy: first, observe the rectal mucosa for signs of congestion, edema, ulcers, or masses to exclude other rectal diseases. Then, examine the area above the dentate line for hemorrhoids. If present, internal hemorrhoids will protrude into the anoscope as dark red nodules, and their number, size, and location should be noted.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Currently, there are the following views on the treatment of hemorrhoids.

1. Asymptomatic hemorrhoids do not require treatment. It is only necessary to pay attention to diet, maintain smooth bowel movements, keep the perineal area clean, and prevent complications. Treatment is only needed when complications such as bleeding, prolapse, thrombosis, or incarceration occur. Hemorrhoids rarely directly cause death, but if improperly treated, severe complications can be fatal. Therefore, the treatment of hemorrhoids should be approached with caution and not taken lightly.

2. The goal of various non-surgical therapies for internal hemorrhoids is to promote fibrosis of the surrounding tissues, fix the prolapsed anal-rectal mucosa to the muscular layer of the rectal wall, and stabilize the relaxed anal cushions, thereby achieving hemostasis and preventing prolapse.

3. Surgery is considered only when conservative treatments fail or when the supporting connective tissues around third- or fourth-stage internal hemorrhoids are extensively damaged.

Based on the above perspectives, the treatment of internal hemorrhoids should focus on alleviating or eliminating major symptoms rather than radical cure. Therefore, relieving the symptoms of hemorrhoids is more meaningful than changes in their size and is regarded as the standard for treatment efficacy.

There are many treatment methods for internal hemorrhoids, and the choice can be made based on the condition.

(1) Injection Therapy

Many drugs are used for injection therapy, but they can generally be classified into two categories: sclerosing agents and necrotizing agents. Due to the higher complication rate associated with necrotizing agents, sclerosing agents are now more commonly recommended. However, excessive injection of sclerosing agents can also lead to necrosis. The purpose of injection therapy is to inject sclerosing agents around the hemorrhoidal mass to induce an aseptic inflammatory reaction, leading to occlusion of small blood vessels and fibrosis, sclerosis, and atrophy of the hemorrhoidal mass. Commonly used sclerosing agents include 5% phenol in vegetable oil, 5% sodium morrhuate, 5% quinine hydrochloride urea solution, and 4% alum solution. Large-dose injections of 5% phenol in vegetable oil have the following advantages: ① At a 5% concentration, a total dose of 10–15 ml can be injected with generally no adverse reactions. With other sclerosing agents, small doses are ineffective, while large doses may cause mucosal necrosis or ulcers. ② Vegetable oil-based solutions are easily absorbed and cause fewer reactions, whereas mineral oil-based drugs are poorly absorbed and may lead to adverse effects. ③ Phenol itself has bactericidal properties, which is beneficial for the easily contaminated anal area. ④ The local scar formation after injection is minimal. Over 100 years of clinical practice has proven that injection therapy causes no hidden harm to the human body and has become a globally recognized treatment.

1. Indications: Injection therapy can be used for uncomplicated internal hemorrhoids. First-stage internal hemorrhoids presenting with hematochezia but no prolapse are most suitable for injection therapy. For controlling bleeding, a single injection can achieve hemostasis with significant effects and a high two-year cure rate. For late-stage (third-stage) internal hemorrhoids, injection can prevent or reduce prolapse. Recurrent bleeding or prolapse after hemorrhoid surgery can still be treated with injection. It is also suitable for elderly or frail patients, those with severe hypertension, or those with heart, liver, or kidney diseases.

2. Contraindications: Any external hemorrhoids or complicated internal hemorrhoids (such as thrombosis, infection, or ulcers) are not suitable for injection therapy.

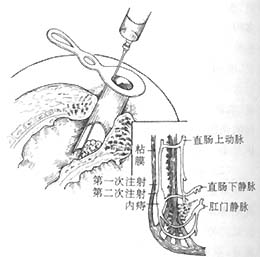

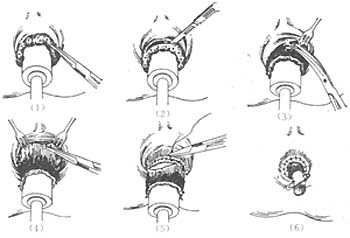

3. Method (Figure 1) The patient should empty their bowels before the injection and assume a lateral or knee-chest position. Using a beveled or rounded proctoscope, disinfect the injection site, then insert the needle tip approximately 0.5 cm beneath the submucosal layer at the base of the hemorrhoid above the dentate line. After insertion, if the needle can move freely left and right, it confirms placement in the submucosal layer. If inserted too deeply into the muscularis mucosa or sphincter muscle, the needle tip will not move easily, and the needle should be withdrawn slightly. After confirming no blood return upon aspiration, proceed with the injection. The needle should not penetrate the central venous plexus of the hemorrhoid to prevent the sclerosing agent from entering the bloodstream and causing acute hemorrhoidal vein thrombosis. Inject 5% phenol in vegetable oil, with the volume determined by the degree of mucosal laxity and the size of the hemorrhoid. Typically, 2–4 ml is injected per hemorrhoid, or up to 6 ml if the mucosa is very lax. For three primary hemorrhoids, the total volume should be 10–15 ml. The solution should be injected into the submucosal layer, forming a pale reddish-white raised area with visible microvessels on the surface—a phenomenon termed the "stripe sign." If the injection is too superficial, the mucosa will immediately turn white and bulge, later necrotizing and leaving a shallow ulcer. If the injection is too deep, penetrating the muscular layer of the intestinal wall, immediate pain will occur. If injected below the dentate line, severe pain will also result. Thus, the depth of injection is critical to the success of this therapy. Avoid injecting in the anterior midline to prevent injury to the prostate, urethra, or vagina. After withdrawing the needle, observe the puncture site for bleeding; if present, apply pressure with a sterile cotton ball to achieve hemostasis. Typically, when the proctoscope is removed, sphincter contraction prevents bleeding or leakage of the sclerosing agent from the puncture site. Repeat injections every 5–7 days, with no more than three internal hemorrhoids treated per session, and 1–3 sessions constituting a course of treatment. The second injection site should be slightly lower than the first. If using 10% phenol in vegetable oil or 5% sodium morrhuate, do not exceed 1 ml per injection, preferably administered with a tuberculin syringe for subcutaneous use.

Figure 1 Injection therapy for internal hemorrhoids

4. Key points of injection therapy ① The first injection is the most crucial. Sufficient dosage ensures good efficacy, but it's preferable to administer smaller doses multiple times. A No. 9 long puncture needle is recommended, as needles that are too thin make it difficult to inject the medication, while overly thick needles may cause bleeding. ② There should be no pain during or after the injection. If pain occurs, it is often due to injecting too close to the dentate line. Therefore, the needle tip must never penetrate below the dentate line. ③ Avoid defecation for 24 hours after injection to prevent prolapse of hemorrhoids. If prolapse occurs, instruct the patient to reposition it immediately to avoid hemorrhoidal vein thrombosis. ④ Before the second injection, perform a digital rectal examination. If the hemorrhoid has hardened, indicating that the mucous membrane is fixed, no further injection is needed. Alternatively, use a blunt needle via an anoscope to test; if the hemorrhoid surface mucous membrane is loose, proceed with injection. ⑤ Injecting too deeply can lead to local necrosis, pain, or abscess formation. ⑥ After injection, the patient should rest in bed briefly to prevent reactions like fainting.

5. Complications Injection therapy with 5% phenol in vegetable oil for internal hemorrhoids is very safe, with few complications. Most complications arise from incorrect injection depth. If the injection is too shallow, it may cause local necrosis and ulceration; if too deep, it may cause injury. For example, injecting the right anterior internal hemorrhoid in males too close to the midline may injure the prostate and urethra, leading to hematuria. Injecting outside the rectum can cause strictures, abscesses, or anal fistulas. Therefore, injection technique must be emphasized.

6. Results Marti (1990) reported a 75% cure rate for stage 1–2 internal hemorrhoids using 5% phenol in vegetable oil injection. Kilbourne (1934) reviewed 25,000 cases and estimated a 1.5% recurrence rate within three years.

(II)Hemorrhoid-necrotizing therapy with troche

The principle involves inserting a necrotizing troche into the center of the hemorrhoid to induce a "foreign body inflammatory reaction," leading to liquefaction, necrosis, and eventual fibrosis of the hemorrhoidal tissue. This method is suitable for stage II or late-stage [stage III] internal hemorrhoids or the internal hemorrhoid component of mixed hemorrhoids. However, it should not be used during acute inflammation of the anorectal region. Necrotizing troches come in two types: arsenic-containing and arsenic-free. Currently, the "Erhuang Necrotizing Troche," made from Phellodendron Bark and Rhubarb Rhizoma, is widely used, offering the same efficacy without the risk of arsenic poisoning.

Method: Place the patient in a lateral position, disinfect and drape as usual, and use a suction device to slowly prolapse the internal hemorrhoid. The operator fixes the hemorrhoid with the left index and middle fingers, then disinfects the hemorrhoid's mucous membrane surface. Holding the rear end of the necrotizing troche with the right thumb and index finger, insert it into the hemorrhoid mucous membrane at an angle parallel to or no more than 15° from the anal canal. Gently rotate and insert the troche to a depth of about 1 cm, not exceeding the hemorrhoid's diameter. Trim any excess troche protruding from the mucous membrane, leaving about 0.1 cm exposed. Space troches 0.2–0.4 cm apart, keeping them about 0.2 cm from the dentate line. The number of troches depends on the hemorrhoid size, typically 4–6 per hemorrhoid per session. Insert troches into smaller internal hemorrhoids first, then larger ones. After insertion, reposition the hemorrhoid into the anal canal. Avoid defecation for 24 hours post-procedure to prevent troche dislodgement, bleeding, prolapse, edema, incarceration, or pain. After each bowel movement, perform a sitz bath with warm potassium permanganate solution. During treatment, administer hemostatic, anti-inflammatory, or laxative medications (Western or traditional Chinese) as needed.

(III)Rubber band ligation therapy

The principle involves using a device to place a small rubber band around the base of the internal hemorrhoid. The band's strong elasticity cuts off blood supply, causing the hemorrhoid to ischemia, necrose, and eventually slough off. This method is suitable for all stages of internal hemorrhoids and the internal hemorrhoid component of mixed hemorrhoids, but it is most effective for intermediate-stage [stage II] and late-stage [stage III] internal hemorrhoids. It is not recommended for complicated internal hemorrhoids.

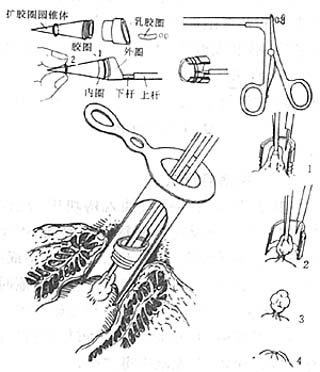

There are two types of instruments for internal hemorrhoid banding: the pull-in banding device (Figure 2) and the suction banding device (Figure 3). The pull-in banding device will be used as an example for explanation. The banding device is made of stainless steel and consists of three parts: ① The front end of the banding ring is the banding loop, with a diameter of 1 cm. It has an inner and outer ring. The inner ring is fitted with a small rubber band (specially made or substituted with a bicycle sweat pore core rubber tube) to encircle the hemorrhoid mass. The outer ring can move back and forth. ② The shaft: This is a 20 cm long metal rod with a handle, divided into an upper and lower rod. The upper rod is connected to the outer ring; pressing the handle causes the outer ring to move forward, pushing the small rubber band on the inner ring out to encircle the base of the hemorrhoid mass. The lower rod is connected to the inner ring and does not move. ③ The rubber band expansion cone is used to load the small rubber band into the inner ring.

Figure 2 Internal hemorrhoid undergoing pull-in ligation therapy

1. The internal hemorrhoid is pulled into the ligation ring; 2. A small rubber band is placed on the internal hemorrhoid; 3. The internal hemorrhoid ligation is completed; 4. The hemorrhoid necroses and falls off

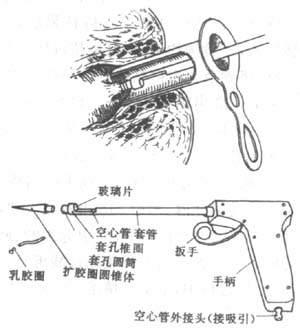

Figure 3 Internal hemorrhoid undergoing suction ligation

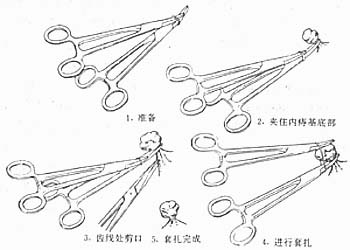

1. Method The patient assumes a knee-chest position or lateral position. Insert the anoscope to expose the internal hemorrhoid requiring ligation. After local disinfection, the assistant fixes the anoscope while the operator holds the ligator in the left hand and the hemorrhoid clamp (or curved grain clamp) in the right hand. The clamp is inserted into the anus through the ligation ring to grasp the hemorrhoid and pull it into the ligator ring. The rubber band is then pushed out to ligate the base of the hemorrhoid. The hemorrhoid clamp is released and removed along with the ligator, followed by the removal of the anoscope. Generally, 1–3 hemorrhoids can be ligated at a time. If a ligator is unavailable, two vascular clamps can be used as an alternative (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Internal hemorrhoid undergoing vascular clamp ligation method

2. Key points ① If the patient complains of pain during clamping, it indicates that the clamping site is close to the anal skin. In this case, reclamp higher up. Keighley (1993) suggested ligating 1.5–2 cm above the dentate line to reduce or even eliminate pain. ② Place two rubber bands on each hemorrhoid simultaneously to prevent band breakage. Rubber bands should not be sterilized under high pressure to avoid increased brittleness and loss of elasticity. ③ It is advisable to ligate no more than three hemorrhoids at a time to minimize anal discomfort. Circumferential hemorrhoids can be ligated in stages. ④ Avoid defecation within 24 hours after ligation to prevent hemorrhoid prolapse, which may lead to edema, incarceration, or bleeding. ⑤ If the ligation site is near the dentate line or involves mixed hemorrhoids, first perform a local anesthetic "V"-shaped incision on the skin on both sides of the hemorrhoid and dissect the external hemorrhoid tissue upward. Then ligate the dissected external hemorrhoid together with the internal hemorrhoid to reduce postoperative pain and edema. ⑥ Postoperatively, perform sitz baths with a hot potassium permanganate solution.

3. Complications ① Bleeding: Generally, a small amount of hematochezia occurs when the internal hemorrhoid falls off, but in rare cases, secondary massive bleeding may occur 7–16 days after ligation. Injecting a small amount of 4% alum solution into the hemorrhoid after ligation can prevent postoperative bleeding and rubber band slippage. Some also inject a small amount of anesthetic into the hemorrhoid to reduce pain. ② Perianal skin edema: This mostly occurs with mixed hemorrhoids and circumferential hemorrhoids. Prevention involves performing high ligation away from the dentate line to reduce pain and perianal skin edema. When ligating mixed hemorrhoids, first perform a "V"-shaped incision on the external hemorrhoid.

The advantages of this method are its simplicity, speed, and lack of need for special preoperative preparation. If the case selection is appropriate and the ligation method is correct, it can achieve painlessness with minimal infection and bleeding. The disadvantages include occasional pain, edema, and bleeding, with a higher recurrence rate compared to surgical excision. Marti (1990) conducted a meta-analysis of 2,025 ligation cases from four authors, reporting cure rates of 69–95%, symptom improvement in 10–25%, and ineffectiveness in 1–10%.

(4) Cryotherapy

Liquid nitrogen (-196°C) is applied through a special probe to contact the hemorrhoidal mass, achieving freezing, necrosis, and shedding of the hemorrhoidal tissue, followed by gradual healing of the wound. It is suitable for initial stage [first stage] and intermediate stage [second stage] internal hemorrhoids. If the depth and scope of freezing are correctly controlled, this method yields good therapeutic results. The drawbacks include prolonged post-operative discharge of mucus from the anus, extended pain duration, slow wound healing, and a high recurrence rate. If rubber band ligation is performed first, followed by freezing the ligated hemorrhoidal mass, tissue injury, necrosis, and secretions can be reduced. Keighley (1979) compared cryotherapy, rubber band loop ligation therapy, and high-fiber dietary therapeutics, with efficacy rates of 38.9%, 65.7%, and 24.3%, respectively. The study concluded that cryotherapy is not superior to high-fiber dietary therapeutics, while rubber band loop ligation therapy is significantly effective in symptom control. Therefore, cryotherapy is not recommended.

(5) Infrared Radiation Therapy

By irradiating with infrared rays, submucosal fibrosis is induced to fix the anal cushions, reduce prolapse, and achieve the goal of curing hemorrhoids. It is suitable for first- and intermediate-stage [second-stage] internal hemorrhoids.

Method: In the lateral position, the hemorrhoidal mass is exposed with an anoscope, and the base of the three primary hemorrhoids is irradiated with an infrared device. Depending on the size of the hemorrhoid, each hemorrhoid is irradiated at 4 points, with each point irradiated for 1–1.5 seconds. Each pulse can produce a necrotic area with a diameter of 3 mm and a depth of 3 mm. The advantages of this method are its simplicity, rapid efficacy, absence of pain, and suitability for multiple treatments. Ambrose (1985) compared infrared photocoagulation therapy with rubber band ligation therapy and concluded that the two methods had similar efficacy, but the former had fewer side effects. Ambrose also compared infrared therapy with injection therapy and found that fewer patients required retreatment with injection therapy. Keighley believed that infrared therapy is only beneficial for grade I and II hemorrhoids and cannot cure grade III hemorrhoids.

(6) Anal Canal Dilation Therapy

Lord (1969) proposed that the presence of hemorrhoids is related to stenosis at the lower end of the rectum and the outlet of the anal canal. During normal defecation, the anal sphincter relaxes automatically, allowing stool to pass easily without significantly increasing intrarectal pressure. If adhesions prevent the sphincter from fully relaxing, leading to anal canal stenosis, stool can only be expelled under pressure. Excessive pressure can cause congestion of the hemorrhoidal venous plexus, resulting in hemorrhoids. The hemorrhoidal mass further obstructs the anal canal, creating a vicious cycle of "congestion–obstruction–congestion." If the stenosis is dilated using anal canal dilation or an internal sphincterotomy is performed, this vicious cycle can be broken, thereby curing the hemorrhoids. This therapy is suitable for patients with high anal canal pressure (resting pressure > 9.8 kPa [100 cmH2O]) or severe pain, such as strangulated internal hemorrhoids. It is not suitable for the elderly, those with enteritis, or diarrhea. Method: See Section 3 on anal fissure. After local anesthesia and anal dilation, regular use of an anal dilator is required for several months. Complications include anal skin tears, submucosal hematomas, and temporary fecal incontinence. Long-term follow-up shows a high recurrence rate. Keighley (1979) treated 37 young male patients (<45 years old) with painful and bleeding hemorrhoids and high anal canal pressure using anal dilation. After one year of follow-up, 11 patients were asymptomatic, 14 showed improvement, yielding an efficacy rate of 76% (25/37). Five patients showed no improvement, four switched to other treatments, and three were lost to follow-up. Complications included bleeding in 4 cases, prolapse in 2, and incontinence in 1. Keighley et al. also compared the outcomes of anal dilation, internal sphincterotomy, and high-fiber diet in patients with high anal canal pressure and concluded that anal dilation was far superior to internal sphincterotomy. Subsequently, Keighley no longer used internal sphincterotomy to treat internal hemorrhoids.

(7) Surgical Therapy

Applicable to stage II, III, and IV internal hemorrhoids, especially mixed hemorrhoids primarily dominated by external hemorrhoids. 1. **External Hemorrhoid Excision and Internal Hemorrhoid Ligation** This involves the **excision of external hemorrhoids** and **ligation of internal hemorrhoids**. **Steps (Figure 5):** ① **Lateral position**, after local anesthesia, use tissue forceps to grasp the skin at the hemorrhoidal site and pull outward to expose the internal hemorrhoid. Make a small "V"-shaped incision on both sides of the hemorrhoid base with scissors, ensuring only the skin is cut without damaging the hemorrhoidal venous plexus. ② Grasp the skin and use a gauze-wrapped finger to bluntly dissect the **external hemorrhoid venous plexus**. Separate upward along the space between the external hemorrhoid venous plexus and the internal sphincter, then slightly incise the mucosal membrane on both sides of the hemorrhoid to fully expose the hemorrhoid pedicle and the lower edge of the internal sphincter. ③ Clamp the hemorrhoid pedicle with curved forceps, tie it with a No. 7 thick silk suture, and then perform a transfixion suture to prevent bleeding due to insecure ligation. Finally, excise the hemorrhoid. For larger hemorrhoids, a continuous suture with 2-0 chromic catgut can also be used on the pedicle. The skin incision does not need suturing to facilitate drainage. ④ Remove the other two primary hemorrhoids using the same method. Generally, a strip of normal mucosal membrane and skin about **1 cm wide** must be preserved between the two excised hemorrhoids to avoid **anal stricture**. Cover the wound with Vaseline gauze.

Figure 5 Mixed hemorrhoids undergoing external hemorrhoid剥离 and internal hemorrhoid ligation

2. Circular Hemorrhoidectomy Applicable to strictly circular hemorrhoids or internal hemorrhoids accompanied by rectal mucosal prolapse. The advantage is the complete removal of circular hemorrhoids at the initial stage [first stage]. The disadvantage is the larger surgical wound, which may lead to anal stricture if postoperative infection occurs, along with more complications. Therefore, it is not commonly used nowadays.

Method (Figure 6): After spinal or sacral anesthesia, place the patient in the lithotomy position, dilate the anal canal, and insert a specially made cork with a diameter matching the dilated anal canal. Fix the hemorrhoidal masses to it using thumbtacks. Make a circular incision near the dentate line, leaving as much anal skin as possible to prevent future mucosal prolapse. Carefully dissect all varicose venous clusters and excise them while suturing intermittently. When cutting the lower rectal mucosa, ensure the anterior and posterior mucosal lengths are equal to prevent postoperative mucosal ectropion. Interruptedly suture the mucosa and skin with 3-0 chromic catgut. If bleeding occurs, add a few more sutures at the mucosal edge. After the incision heals, perform a digital rectal examination. If there is a tendency for stenosis, regular anal dilation is necessary to prevent postoperative anal canal stricture.

Figure 6 Circular Hemorrhoidectomy

(1) Insert the cork, pull out the circular hemorrhoids, and fix them to the cork with thumbtacks; (2) Make a circular incision in the mucosa above the dentate line; (3) Sharply dissect the hemorrhoidal masses; (4) Fix the mucosa to the cork with thumbtacks again 1 cm above the hemorrhoids; (5) Cut and suture intermittently 0.5 cm below the upper row of thumbtacks; (6) Appearance after hemorrhoid excision.

3. Surgical Treatment of Acute Incarcerated Internal Hemorrhoids Internal hemorrhoid prolapse with incarceration, especially acute prolapse and incarceration of circular hemorrhoids (also called acute hemorrhoids), often involves extensive thrombosis and edema. In the past, surgical treatment was avoided due to concerns about infection spreading and complications like portal veinitis, and conservative therapy was commonly used. The drawbacks include prolonged treatment, significant patient suffering, and potential complications like necrosis and infection. Recent studies suggest that acute hemorrhoidal edema results from obstructed venous and lymphatic drainage rather than inflammation. Even if ulcers form, the inflammation is superficial and does not affect deeper tissues, making surgery feasible. Additionally, the perianal tissue has strong resistance to bacterial infection. Therefore, emergency hemorrhoidectomy is recommended, with complications no higher than elective surgery, and postoperative pain and edema are significantly reduced or eliminated. If hemorrhoidectomy or rubber band ligation is unsuitable, lateral internal sphincterotomy can be performed to relieve pain. De Roover reported treating 25 cases of acute hemorrhoids with lateral internal sphincterotomy. Results showed immediate pain relief, with edema, vascular thrombosis, and prolapse improving within days postoperatively. The average hospital stay was 3 days (0–13 days). Among the 25 cases, 20 underwent simple lateral internal sphincterotomy, while the other 5 received hemorrhoid ligation months later. Follow-up over 26 months (1–56 months) revealed 23 very satisfied and 2 somewhat satisfied patients. De Roover believes the advantages of this procedure include simplicity compared to internal hemorrhoidectomy, immediate pain relief, short hospitalization, and the need for only one surgery, with few requiring additional ligation.

There are many treatment methods for internal hemorrhoids. As non-surgical therapy is effective for most internal hemorrhoids, surgical therapy has become less common in recent years, both domestically and internationally. Injection therapy is highly effective for most internal hemorrhoids, especially bleeding hemorrhoids, and should be the first choice. Prolapsed internal hemorrhoids can be treated with rubber band ligation. Due to the potential complications of surgical therapy, strict indications must be followed, and surgery should be reserved for cases where conservative treatment fails or is unsuitable.

It is incorrect to regard hemorrhoidectomy as a minor surgery. If taken lightly, serious complications may occur with even the slightest negligence, potentially leading to major tragedies. Buls (1978) analyzed 500 consecutive cases of hemorrhoidectomy, with the following complications: anal fistula 0.4%, anal fissure 0.2%, anal stenosis 1.0%, fecal incontinence 0.4%, skin tags 6.0%, fecal impaction 0.4%, thrombosed external hemorrhoids 0.2%, and urinary retention 10%.

1. **Bleeding** Postoperative bleeding from internal hemorrhoids can occur in two stages: early and advanced. The former is caused by loose or slipped ligatures, while the latter occurs around 7–10 days postoperatively due to infection at the ligation site. Due to the action of the anal sphincter, blood often refluxes upward into the intestinal cavity rather than flowing outward, making it difficult to detect the "red-stained dressing" clinically. Therefore, such "acute bleeding" is often not easily detected early. The following signs should be considered early indicators of "occult bleeding": ① Paroxysmal borborygmus, intestinal pain, and an urgent sensation of defecation; ② Symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, cold sweating, and rapid pulse, indicating collapse. If these signs appear, a rectal digital examination or endoscopic examination should be performed immediately under pain relief for timely diagnosis and management. Once bleeding is confirmed, hemostasis should be promptly achieved. If there is significant blood accumulation in the anorectal area obscuring the bleeding point, a balloon can be used for compression hemostasis. If a balloon is unavailable, a No. 30 anal tube wrapped in Vaseline gauze, tied tightly at both ends with silk thread, and coated with anesthetic ointment can be inserted into the anus for compression hemostasis. This method is generally effective. If the bleeding point is identified, suture ligation can be used for hemostasis, along with systemic hemostatic medication and antibiotics.

2. **Stenosis** Meticulous surgical technique and early anal dilation can prevent anal stenosis. Stenosis may occur at the anal verge, dentate line, or above the dentate line. Stenosis at the anal verge is mainly due to excessive removal of skin and mucous membrane, leading to wound contraction and narrowing. Scarring is often accompanied by anal fissures caused by tearing during defecation. Manual or instrumental anal dilation is often ineffective, and multiple surgical interventions may be required. Stenosis at the dentate line can occur after closed hemorrhoidectomy, while stenosis above the dentate line results from overly wide ligation at the hemorrhoid base. The latter can be avoided by using multiple small ligations instead of large ones. Anal dilation is often effective; if not, surgical correction may be necessary.

3. **Urinary Retention** Urinary retention is the most common complication after hemorrhoid or other anal surgeries, with about 6% of cases requiring catheterization (Crytal 1974). The following measures can help prevent urinary retention: ① Instruct patients to limit fluid intake before and within the first 12 hours after surgery to induce a grade I dehydration state. This is considered crucial, as premature bladder distension before anesthesia wears off often leads to urinary retention. ② Minimize the use of postoperative sedatives. ③ Encourage early ambulation. ④ For the first urination, the patient should urgently go to the toilet to trigger a conditioned reflex. ⑤ Local anesthesia is preferable. ⑥ Avoid suturing the anal verge skin wound as much as possible, and refrain from placing anal tubes or large gauze packs in the rectum for compression hemostasis postoperatively to reduce pain and primary urinary retention.

The diagnosis of internal hemorrhoids is generally not difficult based on typical symptoms and examinations, but it needs to be differentiated from the following diseases:

- Rectal cancer: Clinically, lower rectal cancer is often misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids, delaying treatment. The main reason for misdiagnosis is relying solely on symptoms without performing a digital rectal examination or anoscopy. Therefore, these two examinations must be conducted in the diagnosis of hemorrhoids. During a digital rectal examination, rectal cancer may present as an irregular, hard mass with surface ulcers, often accompanied by narrowing of the intestinal lumen and blood on the examining glove. It is particularly important to note that internal hemorrhoids or circumferential hemorrhoids can coexist with rectal cancer. One must not be satisfied with a diagnosis of hemorrhoids and proceed with hemorrhoid treatment simply because internal or circumferential hemorrhoids are observed. Only when symptoms worsen might a digital rectal examination or other tests be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Such misdiagnosis and mistreatment, leading to painful experiences, are not uncommon in clinical practice and deserve serious attention.

- Rectal tumors: Low-lying pedunculated rectal tumors, if prolapsed outside the anus, may sometimes be misdiagnosed as hemorrhoidal prolapse. However, polyps are more common in children, appearing as round, solid, pedunculated, and movable masses.

- Rectal prolapse: Sometimes misdiagnosed as circumferential hemorrhoids, but rectal prolapse presents with a circular mucosal surface that is smooth, and the sphincter is relaxed during digital rectal examination. In contrast, circumferential hemorrhoids exhibit a petal-like mucosal pattern, and the sphincter remains non-relaxed.