| title | Ginseng, Tangshen |

| release time | 2006/1/19 |

| source | Jade Knock Studio |

| keyword | Ginseng, Tangshen |

Today, Ginseng refers to the dried roots and rhizomes of the Panax ginseng C.A.Mey., a plant of the Araliaceae family. Cultivated Ginseng is called "Yuan Shen" and is produced in large quantities, while wild Ginseng is known as "Mountain Shen" and is of superior quality. It is mainly produced in Fusong, Ji'an, Jingyu, Dunhua, and Antu in Jilin; Huanren, Andian, Xinbin, and Qingyuan in Liaoning; and Wuchang, Shangzhi, Ning'an, and Dongning in Heilongjiang. It is also produced in Korea and Japan. Tangshen refers to the dried roots of Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., Codonopsis pilosula Nannf. var. modesta (Nannf.) L. T. Shen, or Codonopsis tangshen Oliv. of the Platycodon Root family. Tangshen is mainly distributed in parts of North China, Northeast China, and Northwest China, and has been introduced in many regions across the country. It is the primary source of commercial Tangshen, known as "Lu Dang," mainly produced in Pingshun, Changzhi, Huguan, and Jincheng in Shanxi, and Xinxiang, Luanchuan, and Songxian in Henan. The var. modesta is mainly distributed in Gansu, Shaanxi, Qinghai, and the northwest of Sichuan, known as "Xi Dang," mainly produced in Wenxian, Minxian, Zhouqu, Wudu, and Lintan in Gansu; Nanping, Pingwu, Songpan, and Ruoergai in Sichuan; Hanzhong, Ankang, and Shangluo in Shaanxi; and Wutai Mountain in Shanxi. Codonopsis tangshen is mainly distributed in western Hubei, northwestern Hunan, the border areas of northern and eastern Sichuan, and northern Guizhou, known as "Tiao Dang."

Materia medica research suggests that the "Shangdang Ginseng" mentioned in ancient texts actually refers to the Platycodon Root family's Tangshen, while the Ginseng produced in Liaodong is the Araliaceae family's Ginseng. The history of Shangdang producing Platycodon Root family's Tangshen can be traced back to the Han Dynasty, and the region's advantage in production has been maintained until recent times. Changzhi City in Shanxi and its surrounding areas should be the best region for Tangshen GAP research.

bubble_chart Varietal ResearchThe character for Ginseng should correctly be written as "薓," as seen in the "Wushi'er Bingfang" where "Sophora" is written as "苦浸," with "浸" being a simplified form of "薓." The Han bamboo slips from Fuyang write "紫參" as "紫薓." Originally, "薓" was the specific name for Ginseng, as stated in "Shuowen": "薓, Ren Shen, medicinal herb, from Shangdang." However, by the Han Dynasty, the character "薓" was often simplified to "參," not only in "Jijiu Pian" as "Milkwort Root Dipsacus 參土瓜," but also in "Bencao Jing" where all six instances of "參" use this character, and in the "Wuwei Medical Slips," both Sophora and Ginseng are written as "參." The simplification of "薓" to "參" is still related to Ginseng. According to "Shuowen," "參" refers to the Shang star, which Duan Yucai suggests should be the Jin star. The "Zhou Li·Chun Guan" states, "Shi Shen, Jin also," associating the Shen star with the Jin region. Han Dynasty records of Ginseng's origin all point to Shangdang in Shanxi, as "Shuowen" mentions "from Shangdang," "Bencao Jing" states "grows in the valleys of Shangdang," and "Fan Zi Ji Ran" also notes, "Ginseng from Shangdang, resembling a human, is of good quality." Furthermore, the "Chun Qiu Yun Dou Shu" states, "The scattered light of the Yao Guang star becomes Ginseng; if the benefits of the Jiang Chinese Yam are neglected, then the Yao Guang star will not shine, and Ginseng will not grow." This indicates that the naming of "Ginseng" in the Han Dynasty is indeed related to the celestial Shangxing (GV23) constellation, with "參" hinting at its origin, specifically referring to Shangdang in the Jin region.

So, regarding the "Ginseng" produced in Shangdang during the Han Dynasty, whether it belongs to the Panax genus of the Araliaceae family or the Codonopsis genus of the Platycodon Root family, opinions vary. Most researchers identify the Shangdang Ginseng as Panax ginseng, attributing its extinction in Shanxi to reckless harvesting and ecological destruction leading to phenological changes. However, researchers, whether intentionally or unintentionally, have overlooked a critical issue: Panax ginseng has extremely stringent environmental requirements in its natural state. Apart from factors that can be artificially controlled, such as altitude, light, and precipitation, a half-year dormancy period in a low-temperature environment is indispensable for its growth, a condition that neither modern Shanxi nor ancient Jin possessed. Moreover, since Panax ginseng was mainly sourced from relatively distant regions like Liaodong and even Korea, it is certain that most ancient participants in the discussion about Ginseng had never actually seen the original plant. The description "three branches and five leaves" is actually hearsay. Here, we selectively list records related to "Shangdang Ginseng" after the Han Dynasty:- Fu Xuan's "Fu Zi" states: "The system of the ancient kings was such that the nine regions had different tributes. If the heavens did not provide Unprocessed Rehmannia Root, the nobleman would not consider it a proper offering. For instance, the counties of Henei, though far removed from the northern mountains, were each required to contribute genuine Ginseng from Shangdang, with the superior being ten catties and the inferior fifty catties. The tribute was not native to their land, causing distress among the people." This passage conveys three meanings: the Western Jin Dynasty indeed required "genuine Shangdang Ginseng" as tribute, in the quantities mentioned; the production of Shangdang Ginseng was quite limited, and even Henei Commandery (modern Henan), adjacent to Shangdang Commandery, did not produce it; the precise origin of this Ginseng was in the northern section of the Taihang Mountains, approximately at present-day Zituan Mountain in Changzhi City, also known as Baodu Mountain, located 60 kilometers southeast of Huguan County. The later renowned "Zituan Ginseng" likely originated here.

- Liu Jingshu's "Yi Yuan" Volume 2 states: "Ginseng, also known as earth essence, is best when grown in Shangdang. It has a human-like form and can emit a child's cry. Once, someone dug it up, and as soon as the spade touched the ground, a moaning sound was heard from the soil. Following the sound, they indeed found Ginseng."

- Liu Xiaobiao's annotation in "Shishuo Xinyu·Shijian" quotes "Shi Le Zhuan": "Le, styled Shilong, was from Wuxiang in Shangdang, a descendant of the Xiongnu... Initially, in Le's hometown, stones grew from the earth, increasing daily, resembling iron cavalry. The land produced Ginseng, with lush flowers and leaves. At that time, the elders and physiognomists all said: 'This barbarian has a strange appearance, and his future is unpredictable.'" The phrase "the land produced Ginseng" in the text is cited in the "Ginseng" section of "Yulan" as "the garden produced Ginseng" from "Shi Le Biezhuan." Yu Jiaxi's "Shishuo Xinyu Jiaojian" states: "The 'Jinshu' records it as 'the garden produced Ginseng,' which is correct." According to this, it should indeed be "the garden produced Ginseng." If the Shangdang Ginseng mentioned here refers to Panax ginseng, this would be the earliest record of Ginseng cultivation.

- The "Jizhu" states: "Shangdang Commandery is located southwest of Jizhou, and what the Wei state presented was long and yellow in shape, resembling Saposhnikovia Root, moist and sweet, commonly used but not for medicinal purposes. The more valued was from Baekje, which was slender, firm, and white, with a milder scent than that from Shangdang. Next was from Goguryeo, which is Liaodong, large and soft, inferior to Baekje." Tao Hongjing described the medicinal use of Ginseng in the southern regions during the Qi and Liang dynasties. According to Tao, the Ginseng from Shangdang was "long and yellow, resembling Saposhnikovia Root, moist and sweet," which clearly refers to the Platycodon Root family's Tangshen Codonopsis pilosula. The Ginseng from Baekje (southwest of the Korean Peninsula) was "slender, firm, and white," resembling the Araliaceae family's Ginseng Panax ginseng. However, Tao Hongjing had certainly never seen the Ginseng plant, and his description was a compilation of various sources: "Ginseng grows with a single stem straight up, with four or five opposite leaves, and purple flowers. The people of Goguryeo praised Ginseng, saying: 'Three branches, five leaves, facing the shade, turning away from the sun. If you seek me, look under the catalpa tree.' The catalpa tree's leaves resemble those of the tung tree, very large, and it grows abundantly in shady places. Harvesting it is quite methodical. Nowadays, it can also be found near mountains, but the quality is not good." In Tao's description, the plant with "a single stem straight up, four or five opposite leaves, and purple flowers" is actually the Platycodon Root family's Adenophora tetraphylla (Thunb.) Fisch. The praise from Goguryeo refers to the Araliaceae family's Ginseng, while "nowadays, it can also be found near mountains" is unclear what it refers to. No wonder Su Jing criticized: "Tao's description of Ginseng's seedling is actually Apricotleaf Ladybell Root and Platycodon Root, failing to understand the praise from Goguryeo."

- The "Sui Shu·Five Elements Zhi" states: "During the reign of Emperor Gaozu, there was a person in Shangdang whose house had a voice calling every night, but no one could be found. About a mile from the house, only a single Ginseng plant was seen, with lush branches and leaves. Upon digging it up, its root was over five feet long, resembling a human figure, and the calling ceased, hence it was considered a grass demon." In this legend, the Shangdang Ginseng also grew not far from human habitation, and its form is described as "lush branches and leaves," similar to the "lush flowers and leaves" mentioned in the previous "Shi Le Biezhuan," neither of which are characteristics of Panax ginseng. The claim of a root five feet long is an exaggeration.

- In the Tang Dynasty, it seems that there was still a belief that ginseng from Shangdang was superior to that from Liaodong and Korea. The Yaoxing Lun states: "Ginseng, grown in Shangdang County, is the best when it resembles a human shape. The next best comes from the eastern sea, from the Silla Kingdom, and also from Bohai." The Classic of Tea, Volume One, mentions: "Tea is a burden, much like ginseng. The best grows in Shangdang, the medium quality in Baekje and Silla, and the lowest quality in Goryeo."

- People of the Song Dynasty particularly liked to praise the so-called "Zituan Ginseng," which came from Zituan Mountain in Shangdang. The Kaibao Bencao states: "The ginseng produced in the Taihang Mountains of Luzhou is called Zituan Ginseng," and the Erya Yi agrees. Volume 9 of the Mengxi Bitan records: "When Wang Jinggong suffered from asthma, he needed Zituan Mountain Ginseng, but it was unavailable. At that time, Xue Shizheng had just returned from Hedong and happened to have some, so he offered Wang a few taels. Wang refused, but someone advised him: 'Your illness cannot be cured without this medicine. The illness is worrisome, and the medicine should not be declined.' Wang replied: 'I have lived to this day without Zituan Ginseng,' and ultimately did not accept it." Was this "Zituan Ginseng" truly Panax ginseng? In Volume 37 of Su Shi's Poetry Collection, "Zituan Ginseng Sent to Wang Dingguo," it is written: "I wish to hold the three-branched root to accompany the nine-cycle cauldron." Judging from the verse, this naturally refers to Panax ginseng. However, when Su Dongpo resided in Huizhou, he also wrote "Five Odes to the Small Garden: Ginseng," found in Volume 39. The opening lines read: "Shangdang is the ridge of the world, Liaodong truly the bottom of a well. Dark springs pour forth the richness of the sea, White Dew sprinkles the nectar of heaven. Here, the spiritual sprout is nurtured, its limbs taking form. Transplanted to Luofu, watered by the clear streams of Yue." Additionally, according to the same volume, in "Following the Rhyme of Zhengfu's Journey to Baishui Mountain," the line "Carefully hoeing yellow soil to plant three branches" is annotated by Su Shi himself: "Zhengfu shared a ginseng seedling with me, which I planted in Shaoyang." Based on these two poems, Su Shi indeed transplanted the so-called "ginseng" to a garden in Huizhou, Guangdong. This plant could not possibly be Panax ginseng. Clearly, Su Dongpo did not truly understand the ginseng plant, and his descriptions of "three branches and five leaves" were merely borrowed from earlier accounts.

Let us assume that Liaodong Ginseng and Shangdang Ginseng originate from different plants. In fact, this phenomenon of different substances sharing the same name was quite common in ancient materia medica. As history progressed, the outcomes of such phenomena could be summarized into three possibilities: if both substances had equivalent medicinal effects, they would continue to share the same name, such as Dyers Woad leaves and Isatis Root; if both had medicinal effects but differed in their actions, they would be differentiated into two distinct drugs, such as Achyranthes Root and Cyathula Root, or Southern Glehnia; if one of them was ineffective, it would gradually be phased out. If this assumption holds true, the fate of these two types of Ginseng would follow a similar pattern.

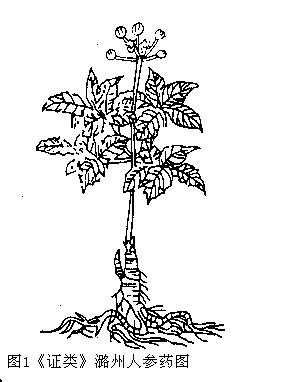

Tao Hong-jing, in the preface to *Bencao Jing Jizhu*, lamented that "Shangdang Ginseng is almost no longer sold," yet in the main text of the Ginseng entry, he stated: "Shangdang Commandery is located southwest of Jizhou, and what is now presented by the Wei State is long and yellow in shape, resembling Saposhnikovia Root, moist and sweet in texture, but it is not commonly used for medicinal purposes. Instead, the Ginseng from Baekje, which is slender, firm, and white, with a milder taste than Shangdang Ginseng, is preferred." This passage subtly hints at the differences in appearance between Liaodong Ginseng and Shangdang Ginseng. However, since both Liaodong and Shangdang were under the Northern Dynasties at the time, Tao Hong-jing did not have the opportunity to understand the morphological differences between the two plants. He vaguely mentioned that Shangdang Ginseng was "not commonly used for medicinal purposes," implying that it was inferior to Liaodong and Korean Ginseng. The *Xinxiu Bencao* did not comment on Tao's views but simply outlined the distribution range of Shangdang Ginseng, as quoted above. Su Jing's silence on Liaodong Ginseng had its own reasons. The *Xinxiu Bencao* was completed in the second year of Emperor Gaozong's Xianqing era (659), and before the fall of Goguryeo in the first year of the Zongzhang era (668), when the Tang government established the Andong Protectorate in present-day Pyongyang, most of Liaodong was occupied by Goguryeo. Emperor Taizong of Tang once lamented, "Liaodong was once part of ancient China, but since the Wei and Zhou dynasties, it has been neglected. The Sui dynasty launched four military campaigns, all of which ended in defeat, resulting in the loss of countless Chinese lives." This statement is recorded in the *Cefu Yuangui*, in the section on imperial expeditions. Thus, it is understandable why Tang-era civilians or physicians, such as those mentioned in the *Tea Classic* and *Yaoxing Lun*, insisted that Shangdang Ginseng was superior to Liaodong Ginseng. The first officially compiled materia medica of the Song dynasty, the *Kaibao Bencao*, acknowledged: "Ginseng is now mostly from Goryeo and Baekje. The Ginseng from the Taihang Mountains in Luzhou, known as Zituan Ginseng, is also used. Tao's claim that it is not commonly used for medicinal purposes is incorrect." This implies that Shangdang Ginseng was inferior to Liaodong Ginseng, though still usable. Compared to Ma Zhi's *Kaibao Bencao*, the *Bencao Tujing* compiled by Su Song in the sixth year of the Jiayou era (1061) was much more rigorous. First, "the emperor ordered all prefectures and counties to submit illustrations of locally produced medicinal plants." Su Song and his team "collected various accounts, categorized them, and arranged them systematically." When encountering cases where "one substance was produced in multiple regions" or "different substances shared the same name but had entirely different forms," they "cross-referenced ancient and contemporary accounts to elucidate each other." From the over 900 illustrations preserved in the *Zhenglei Bencao*, the medicinal illustration of "Weishengjun Ginseng" stands out as particularly unusual. Not only does it differ significantly from the Ginseng produced in Luzhou, despite the close proximity of the two regions, but the stark contrast in the level of detail between the two illustrations is also surprising. Moreover, the fact that the "Weishengjun Ginseng" illustration does not depict the medicinal part (the root) is even more peculiar.

During the Northern Song period, mainstream Ginseng could be categorized into three types based on the political situation and its origin: the first type was Shangdang Ginseng, distributed in the Taihang Mountains controlled by the Song Dynasty; the second type was Liaodong Ginseng, produced in the Jurchen-controlled regions within the territory of the Liao Dynasty, as detailed in Volume 22 of "Qidan Guozhi" by Ye Longli of the Southern Song; the third type was Goryeo Ginseng, produced in Goguryeo. We note that although Su Song and the slightly later Kou Zongshi both emphasized that the domestically produced Shangdang Ginseng was far superior to the imported Goryeo Ginseng, they had to admit that Ginseng at that time mainly relied on imports. The "Tujing" states: "There is also Ginseng from the Hebei border markets and Fujian, known as Silla Ginseng, but all are inferior to the Shangdang variety." The "Yanyi" also says: "The Ginseng used today is all obtained through trade at the Hebei border markets, mostly from Goryeo, generally weak in flavor and thin, not as rich and substantial as the Shangdang Ginseng from Luzhou, which is reliable in use." Since the Song Dynasty was often in a state of hostility with the Liao Dynasty, the border markets were intermittently open and closed, which is why Su and Kou mainly discussed Goryeo Ginseng and not Liaodong Ginseng. Regarding the import of Goryeo Ginseng, a historical record is preserved in Volume 6 of the Southern Song's "Baoqing Siming Zhi," which is too lengthy to quote here.

On the basis of understanding the political background of the time, we speculate that the pharmaceutical census conducted by Su Song likely discovered differences in plant morphology and efficacy between Shang Tangshen and Liaodong or Korean ginseng. However, due to the significant status of ginseng in the medical field at that time, in order not to show weakness in border trade to the enemy (Liao Dynasty or Korea), the fact that Shang Tangshen was not the commonly known "three branches and five leaves" Panax ginseng was deliberately concealed. Instead, a meticulously drawn "Luzhou Ginseng" medicinal illustration was created based on the morphology of Korean ginseng, accompanied by a very accurate textual description to deceive the enemy. As for the specially drawn, somewhat incongruous "Weisheng Army Ginseng" illustration, it had another purpose. This illustration was likely used to suggest to the officials of the "Medicine Procurement and Verification Office" in the Shangdang Ginseng production area that such an ambiguous plant could also be considered as ginseng. The plant this illustration intended to represent was probably the Platycodon Root family's Tangshen Codonopsis pilosula, which has been produced in Shangdang since ancient times. In fact, Kou Zong-shi, an official of the "Medicine Procurement and Verification Office" slightly later than Su Song's time, did notice the differences between Shang Tangshen and Korean ginseng. Bencao Yanyi states: "(In Shangdang) locals, upon finding a nest, place it on a board, tie it with colored floss, the roots are quite slender and long, not similar to those in the market. Some roots hang down more than a foot, or have ten branches, their price is equal to silver, and they are somewhat hard to obtain."

How many people were aware of the secret created by Su Song at that time is unknown. Although the story about Wang Anshi refusing to take Shangdang Zituan Ginseng in Mengxi Bitan was widely circulated for a time, it cannot be easily cited as evidence that Wang Anshi knew the inside story, let alone serve as evidence supporting this speculation. However, 66 years after Su Song compiled Bencao Tujing, the entire northern region, including Shangdang, fell into the hands of the Jurchens, who established the Jin Dynasty, and the secret of Shangdang Ginseng was no longer a secret. Two medical books from the Jin and Yuan periods inadvertently revealed the truth. Liu Wan-su (1120-1200) from Hejian (today's Hejian, Hebei) in the Jin Dynasty, in Huangdi Suwen Xuanming Fang Lun Volume 9 "Xianrenzhi Pill", used ginseng and Zituan Ginseng together. Slightly later, Wang Hao-gu (about 1200-1264) from Zhaozhou (today's Zhaoxian, Hebei) in the Yuan Dynasty, in Yilei Yuanrong Volume 12 Ziwan Pill, for treating five types of wind and leprosy diseases, also used Zituan Ginseng and ginseng simultaneously. The hometowns of both Liu and Wang were not far from Shangdang, and Liu Wan-su's era was less than a hundred years after Su Song's Tujing, yet both realized that the so-called Shangdang Zituan Ginseng was different from ginseng. This cannot be explained by the depletion of Panax ginseng in Shangdang from the Song to the Jin Dynasty and its replacement with Codonopsis pilosula.

From this, we know that the so-called Shangdang Ginseng was actually Platycodon Root family's Tangshen. At least by the Northern Song Dynasty, this secret had been discovered but was forced to be concealed due to special reasons. However, starting from the Jin Dynasty, the so-called "Shangdang Zituan Ginseng" was undoubtedly Tangshen. Subsequently, the medicinal evolution of Araliaceae ginseng was relatively straightforward. Bencao Gangmu states: "Shangdang is now Luzhou, where the people consider ginseng a local nuisance and no longer collect it. What is used now is all Liaodong ginseng. The three countries of Korea, Baekje, and Silla are now all part of Korea, and their ginseng still comes to China for trade." Except for attributing the disappearance of Luzhou Ginseng to "the people considering ginseng a local nuisance and no longer collecting it," Li Shi-zhen's account of its medicinal use has not changed much to this day, and there is no need for further elaboration.

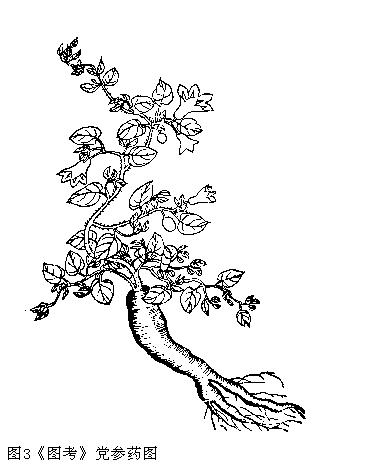

As for the name Tangshen, it actually evolved from "Shangdang Ginseng." In volume 4 of *Gufuyuting Zalu* by Qing dynasty scholar Wang Shizhen, it is recorded: "Wang Jie once said, 'I have lived to this day without ever having consumed Zituan Ginseng.' Note that Zituan is the name of a mountain in Shangdang. Materia medica and texts from the Tang and Song dynasties onwards have all valued Tangshen. Today, only ginseng produced in Liaodong and Korea is highly prized, with the best quality fetching up to five taels of silver per liang. In contrast, Shangdang ginseng costs only two qian of silver per jin. Recently, due to strict restrictions on ginseng, its price has skyrocketed, and Tangshen has begun to be used as a substitute, with its price rising to over one tael of silver per jin. However, it is still not easy to obtain." Tangshen was officially recorded in materia medica in *Bencao Congxin*, where Wu Yi-luo stated: "According to ancient materia medica, the best ginseng comes from Shangdang. Genuine Tangshen has long been difficult to find. The Tangshen sold in markets comes in many varieties, most of which are unusable. Only Saposhnikovia Root Tangshen, with its mild and balanced properties, is truly valuable. Those with roots resembling a lion's head are genuine, while those with hard patterns are fake." *Zhiwu Mingshi Tukao* states: "Tangshen is widely produced in Shanxi. Its roots can grow two to three feet long, and it is a creeping plant with asymmetrical leaves and joints as thick as a finger. Wild varieties have roots with white sap, and they bloom in autumn with flowers resembling those of Coastal Glehnia Root, colored bluish-white. Locals cultivate it for profit." In *Bencao Gangmu Shiyi*, under the entry for "Saposhnikovia Root Tangshen," Weng Youliang's clarification is cited: "The efficacy of Tangshen can substitute for ginseng. Its skin is yellow with horizontal patterns, resembling Saposhnikovia Root, hence it is also called Fangdang. In regions like Huizhou in Jiangnan, it is referred to as Lion's Head Ginseng due to its large, round, and convex root crown." Additionally, *Baicao Jing* is quoted: "Tangshen is also known as Huang Shen. Those with a yellow and moist appearance are of good quality, produced in areas like Lu'an and Taiyuan in Shanxi. Some are white, but the best are those that are clean, soft, robust, and sweet. Young and small branches are called Shang Tangshen, while older and larger ones are called Fang Tangshen." The so-called "Saposhnikovia Root Tangshen" mentioned in the text is also known as "Fang Tangshen." In volume 35 of *Xu Mingyi Lei'an*, it is stated: "In the Returning to Spleen Decoction, ginseng and Aucklandia Root are removed, and Fangshen is added." Combining this with the medicinal illustration of Tangshen in *Tukao* (Figure 3), it is evident that Tangshen, Fang Tangshen, and Saposhnikovia Root Tangshen are all *Codonopsis pilosula* or its variant *Codonopsis pilosula var. modesta*.

In the "Bencao Gangmu Shiyi," there is a mention of "Chuan Dang," stating: "Recently, there is Chuan Dang, which is adjacent to Shaanxi, transplanted and cultivated, with white skin and a mild taste, similar to Platycodon Root, without a lion's head, quite different from that of Shanxi." The morphological feature of "without a lion's head" here is similar to the so-called small strips in Chuan Tangshen, where the root head is smaller than the main body, referred to as "mudfish head." Therefore, this species should be the Codonopsis tangshen used today.

bubble_chart Historical Evolution of Authentic Regions

In the section on variety identification, we have used extensive text to discuss the name and reality of Shangdang Ginseng, as this issue relates to the establishment of modern Ginseng and Tangshen GAP bases. If the ancient Shangdang Ginseng was indeed Panax ginseng, then Changzhi City in Shanxi today has every reason to conduct GAP research on Ginseng, and it might even be possible to cultivate medicinal materials surpassing those from the Northeast. But if not, then the history of Codonopsis pilosula production in Shangdang can be traced back to the Han Dynasty, and the regional advantage has been maintained until recent times, making this area the best region for Tangshen GAP research.

Through historical review, it can be clarified that the earliest recorded origin of Panax ginseng is Liaodong, as mentioned in the "Mingyi Bielu." The standard origin has not changed much from ancient to modern times, as stated in the "Huangchao Tongzhi" Volume 125 of the Qing Dynasty: "Ginseng, with three branches and five leaves, sometimes resembling a human figure, is produced in the deep mountains of Liaoyang and is considered a top-grade medicinal in medical classics. It is a sign of the long-lasting royal aura, nurtured by the divine land. The Ginseng produced in Jilin Ningguta and other places is of slightly inferior quality, and what is called Shang Tangshen is just like ordinary flowers."

Tangshen is the ancient "Shangdang Ginseng," with its original production area in Shangdang, Shanxi. According to the "Xin Xiu," it can be planted along the Taihang Mountains. As for the records of Xi Dang and Tiao Dang, they are later, and research can be conducted based on cultivation habits in various regions.

bubble_chart Other Related Items